This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on China and Latin America | Leer en español | Ler em português

The three global capitals furthest from Beijing are Santiago (11,836 miles), Montevideo (11,895) and Buenos Aires (11,964). When you consider those distances, and the relative lack of historical and cultural ties, China’s expansion in Latin America over the past two decades looks even more extraordinary.

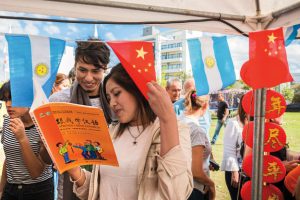

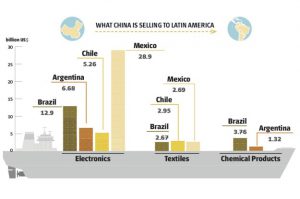

This issue of AQ is a sweeping, nuanced portrayal of the Sino-Latin American relationship as it stands today — deep, sophisticated and increasingly under some strain. China is now Latin America’s second-biggest trading partner behind only the United States. For many countries, it has been #1 for years. Beijing buys not only Colombian oil and Brazilian iron ore, but invests in dams, railroads and electrical grids. Chinese cell phones and SUVs have become popular. Thousands of Latin Americans now study in the Middle Kingdom; many like it enough to stay, excelling in areas like technology and the arts — and building a foundation for even closer ties in years to come.

Many governments are similarly delighted. But there are also signs of a backlash. Leaders in Brazil, Ecuador and El Salvador are calling for change, worried about everything from predatory loans to China’s acquisitions of land and strategic minerals like lithium. There is growing talk in Latin American diplomatic circles of forming a common front to press China for better terms on trade and investment. Beijing’s continued support for the Venezuelan dictatorship has also alienated many.

Perhaps some of this was inevitable; rising powers always undergo a learning process. But it would be wise for all parties to pursue an updated, 2.0 version of the China-Latin America relationship. For Beijing, that means realizing it cannot do business the way it has in parts of Africa and Asia — intellectual property, environmental and labor laws, along with democracy itself, must be respected. For Latin America, it means not taking China for granted, and working to improve the business climate; Chinese trade and investment have quietly gone stagnant in recent years as Beijing focuses on more dynamic markets elsewhere.

The Trump administration has been encouraged by these recent strains, hoping to gain new allies in its global competition with China. But as this issue shows, economic and political ties are already so deep that most governments — even those like Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil — will be loath to hit Beijing too hard. A reset, rather than a rupture, looks like the most likely path forward. It seems China is in Latin America to stay.