CARACAS—In less than 72 hours, Venezuela’s outlook has changed. On Tuesday, the government and the opposition’s Unitary Platform inked a new political agreement, setting the stage to carry out open and fair general elections in the second half of 2024. A day later, Maduro’s administration released high-level political prisoners, and the U.S. lifted most of its sanctions on oil, gas and gold, throwing a lifeline to a reeling economy that could eventually end the pariah-like status for the nation and its extractive industry. The speed of the events and their profound implications still raise questions about whether the steps will pave the way to a democratic transition in the country.

So far, the political agreement and the sanctions relief seem to be some of the most significant achievements of the negotiation process that both parties have participated in for years, especially since the U.S. enacted multiple sanctions against Venezuelan officials, public banks and public industries after authoritarian President Nicolás Maduro was re-elected in sham elections in 2018. Under Maduro’s decade in power, Venezuela has experienced notorious political repression, a prolonged and unprecedented humanitarian crisis, mass exodus and an economic contraction rarely seen in countries not enduring the chaos of war. Since the beginning, the U.S. has directly met with officials of the Maduro regime, hoping to achieve free and fair presidential elections next year in exchange for sanctions relief.

“It is a small and vulnerable window of opportunity,” Michael Penfold, a Venezuelan political scientist and author, told AQ in Caracas, noting that its viability will hinge on the “quality of the execution and verification of the agreements” achieved.

Under the eased sanctions, Venezuela is authorized for the next six months to export oil and gas to the U.S. and other countries, repay debt related to its oil operations, and honor defaulted obligations with its creditors and the state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela SA, PDVSA. At the same time, international companies can make new investments in the hydrocarbon sector. But the broad relaxation comes with a critical caveat issued by Antony J. Blinken, the U.S. Secretary of State: Before the end of November, Venezuela’s government needs to define “a specific timeline and process for the expedited reinstatement” of all candidates who want to run for president next year.

And this means that the next six weeks will be essential to solidifying the recently enacted political accords. “Without a doubt, the bans from running for office are [the] Achilles heel” of the agreements, Penfold says.

Leading the opposition

The first test of this new scenario comes in days as the opposition holds primary elections on Sunday, October 22. Around 8% of the Venezuelan electorate is expected to participate, says Félix Seijas, who leads local pollster Delphos. “Nowhere in the world [does] a primary election [have] high participation percentages,” he said in a recent interview. “This number, in these very adverse circumstances, is quite good.” According to Delphos’ polls, expectations for change have risen, and people’s willingness to vote has resurfaced even before the agreements achieved in recent days.

While center-right candidate María Corina Machado is widely expected to win the opposition primaries on Sunday, divisions run deep within a fractured opposition. Machado—who has been critical of the main opposition parties—was banned in June from running for office by the government, a legal situation that has unleashed a debate within the opposition about a possible replacement.

According to political scientist Stefania Vitale, the Maduro regime uses “cooptation and repression” to deepen divisions in the opposition. “Bans from running for office are a tool the government has used to diminish the opposition’s opportunities” and generate internal conflicts, she told AQ.

Similarly, despite Machado’s rapid rise, Vitale says the main opposition parties are “weakened.” Most have lost their representation on the electoral ballot, which was handed to puppet boards through judicial rulings, and the government has also promoted parallel “opposition” candidates outside the primaries. And, unlike its predecessor, the Democratic Unity Roundtable, the opposition’s Unitary Platform “doesn’t have formal and clear rules,” she says, even if “the parties are making an important effort to align.”

Nevertheless, recent polls show that a vast majority of Venezuelans want political change, support the idea of a unitary opposition candidate, and are willing to vote in 2024—a process that, following the Barbados agreements, seems likely to be more competitive. Yet if the opposition wants “an effective, solid and realist strategy” in 2024, Vitale says, “coordination between the opposition forces will be key.”

De-sanctioning oil

Since 2019, oil operations have been restricted to European oil companies and Chevron Corp., which has become the main buyer of Venezuelan state-owned oil. “Until now, basically, everyone except the Russians can do whatever they want” in the oil industry, Francisco Monaldi, a leading scholar on energy economics and a fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute, told AQ.

The cash-strapped Maduro government had sought new revenues to feed its clientelist networks as the 2024 elections approach. “Even if the Americans revert everything in six months, they [the Maduro government] will have collected a bunch of money for the elections,” Monaldi said, “The Venezuelan treasury’s income could more than double.”

While he believes that most companies will still be cautious about making significant investments in the industry, Chevron—which could increase its current output by 110,000 barrels per day (bpd) in the next 18 months—could be followed by European companies like Maurel & Prom, Eni and Repsol as well as Chinese firms, which would add another 100,000 bpd.

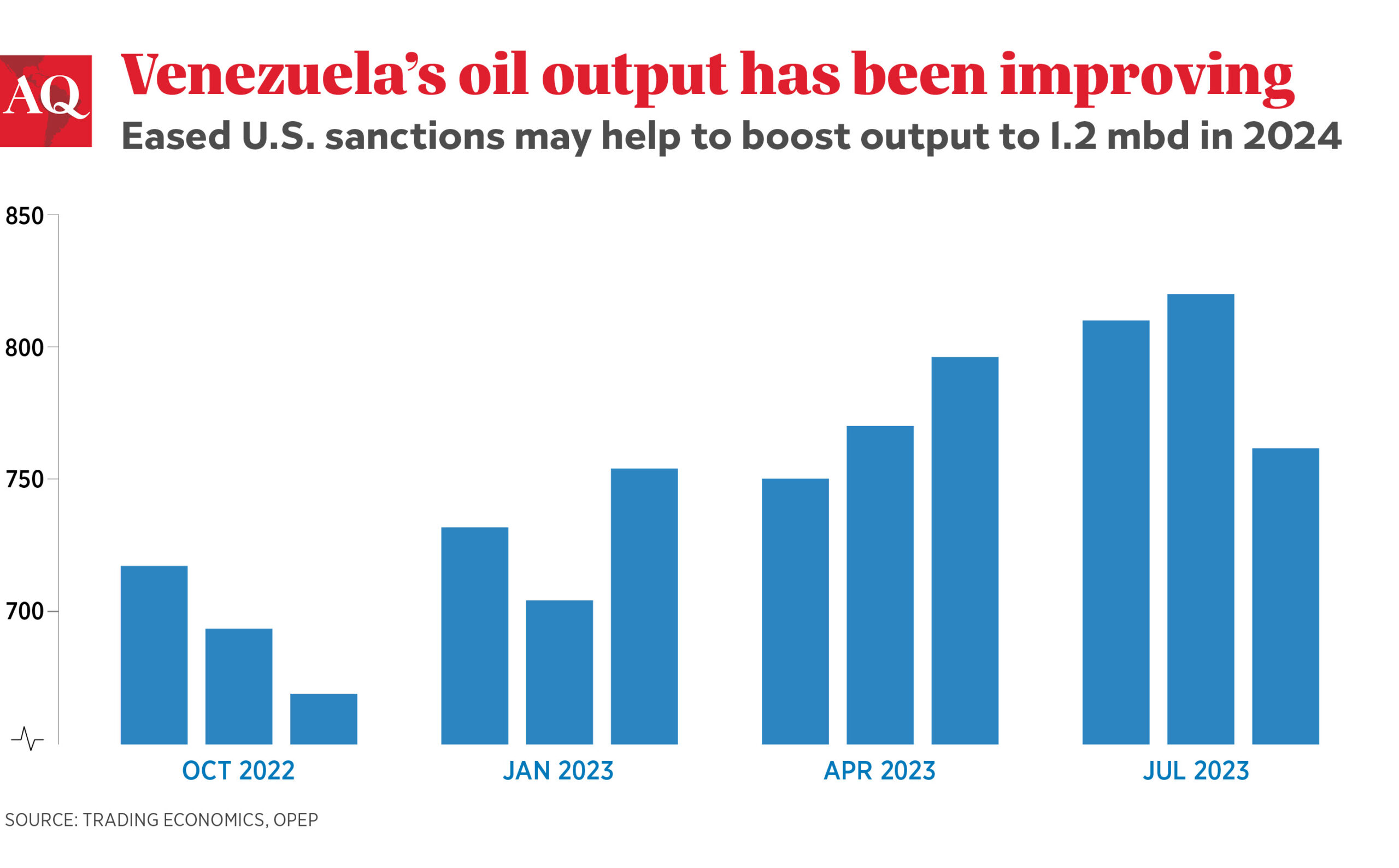

Under this scenario, Luis Bárcenas, senior economist at Caracas-based research firm Ecoanalítica, says Venezuela may start pumping over 1.2 million bpd on average in 2024, the highest level since early 2018. That would still be far from the 2 million bpd the country produced in 2012, the year before Maduro succeeded the late President Hugo Chávez Frías.

This could more than double Venezuela’s oil revenues from the $11 billion expected in 2024 before the relief and may result in Venezuela’s GDP growing 10% or more if the license is expanded or extended beyond the initial six months announced. Before easing the sanctions, the economy was expected to grow about 4.4% next year. Ecoanalítica predicts the country’s economic growth could be insignificant for this year or even endure a contraction of close to 1%.

While the accords achieved may inject a new hope, “this is a first partial agreement,” said Gerardo Blyde, a former mayor and the head of the opposition’s negotiation delegation that inked the deal with Maduro’s government. “Many points we discussed in the memorandum of understanding in Mexico are still missing,” referring to the memorandum both parties signed in 2021, when the current negotiations began.