Days after José Antonio Ocampo agreed to become President-elect Gustavo Petro’s finance minister, he said to a reporter from El País: “I’m in this because he talks about creating a grand national consensus. I have not been a petrista until now.”

Ocampo, 69, is an economist and self-described center-left social democrat. He worked on the presidential campaign of one of Petro’s opponents, centrist Sergio Fajardo, who lost in the first round. But as of August 7, he will hold the most important cabinet position in Colombia’s first-ever leftist government.

Colombia, a middle-income country, is short on cash and Ocampo has defined his mission as increasing social spending, but doing so without sacrificing fiscal stability.

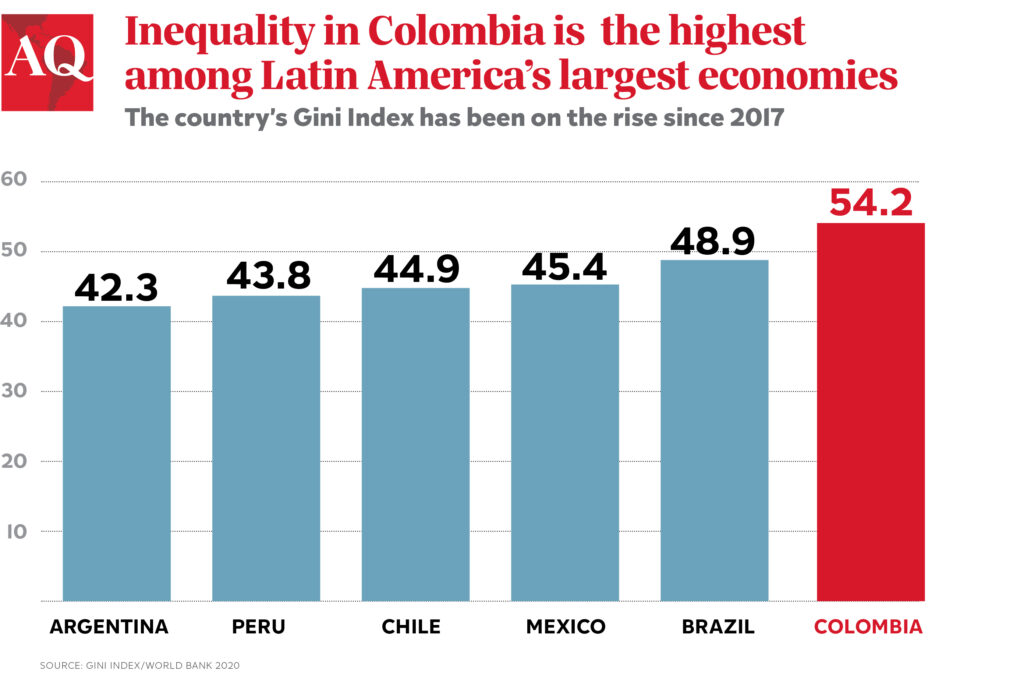

Bridging divergent economic views will be a big part of his job. The task is made harder because Colombians’ social demands have risen in recent years, which in part explains Petro’s victory. Ocampo has tried to be a moderate voice in public office before, in the 1990s, in a right-leaning government. Will he succeed this time?

Leveraging his reputation

Ocampo and Petro may disagree on many things, but they share some core views. Both have said a tax reform will be their priority, and that it should include raising taxes for Colombians who are better off. Indeed, part of Ocampo’s role seems to be to use his reputation to disarm resistance to Petro. He called upon himself to convince the rich of the importance of the tax reform, and he is the government’s bridge with business leaders.

Ocampo has the respect of Colombia’s business community and international investors due to his long list of credentials. He has governmental experience, having been minister twice in the mid-1990s, and co-director of the Banco de la República, Colombia’s central bank. He had leadership roles at the United Nations and several other institutions and has a respected academic background.

To Silvana Amaya, a senior analyst at Control Risks, the nomination of Ocampo helped calm investors’ fears over possible sweeping reforms. “We can expect a minister of finance who will manage changes responsibly. He understands how some decisions can affect industries. And he is a firm defender of his beliefs. The business community knows that and trusts him,” she said.

His time as minister in the 1990s

This is not the first time that Ocampo joins a government he was not entirely in line with. In 1993, he became minister of agriculture in the presidency of César Gaviria, whose administration is remembered for pro-globalization neoliberal reforms in a period that became known as the apertura económica.

Ocampo was generally in agreement with the apertura, but he opposed the speed and depth at which it was being implemented by then-Finance Minister Rudolf Hommes, who led the way for privatization of public companies and a reduction in barriers to trade. “Ocampo is not a crazy protectionist,” said Javier Mejia, a Colombian and professor of economic history at Stanford University, “but he always had an idea of a government that supports industry through some protection.” Gaviria sided with Hommes in the debate, resulting in Ocampo’s departure in 1994.

He returned in the following government, under Ernesto Samper, with whom Ocampo was more ideologically aligned. The Samper government had ambitious social plans, and it was known that Ocampo, as Samper’s longtime advisor, was pushing for them.

However, by the time Ocampo joined, the Samper government’s political capital was spent, with the chief prosecutor accusing him of having received money from the Cali drug cartel to finance part of his presidential campaign, an accusation of which he was acquitted by the lower house in 1996. Nevertheless, the damage had been done. “There was not much he could do and the economy was governed almost by inertia. Those were not the best times to be in office,” said Mejia.

Colombia has the lowest personal income tax to GDP ratio among OECD members

Fixing Colombia’s tax system is a priority

Only 5% of Colombians pay personal income taxes. What is collected comes mostly from corporate taxes.

Petro said during the campaign that he hopes to raise 50 billion Colombian pesos (roughly $12 billion), and part of his plan was to tax the 4,000 richest Colombians. In a recent interview with Portafolio, Ocampo moderated that goal, saying they hope to reach 50 billion pesos over the course of Petro’s four years in government. He plans to do that in part by closing loopholes that favor Colombians who make more than 10 million pesos per month ($2,200), which according to him is around 2% of the population.

How the reform will play out politically remains to be seen. Petro and Ocampo hope to get it through Congress in the administration’s first year, making the most of a majority there in his first year. Petro’s congressional alliance, an ideological mix of parties, currently has the numbers to take the proposal to the floor. But the shape of the draft could change considerably as it moves through committees.

Petro has many ambitious plans, some of which Ocampo shares, at least in principle. Pushing Colombia’s economy away from fossil fuels and into a greener future is one of them. In the campaign Petro promised he would ban new exploration for oil and coal and cancel fracking projects. Ocampo has said recently that he is in favor of stopping new oil exploration, but not gas, which he hopes could keep the economy afloat while the country transitions to clean energy sources.

However, it is not clear if Ocampo will be around to deliver on that. Many analysts say that he will likely not remain minister for the full four years of the new administration. Petro may soon have to cede the finance ministry to one of the many groups with which he is in government. Both are seen as firmly opinionated. If tax reform and energy are subjects where they generally agree, Ocampo has signaled that he would not follow through with at least two of Petro’s other campaign promises: the proposed pension reform and the idea of making the state a guaranteed employer for those who cannot find work.

In interviews, Ocampo acknowledges that he has a lot on his plate, and that external conditions will make his tenure difficult. The fiscal deficit is at 7%, the highest in years, and inflation is at 9%, the highest in decades. The Colombian peso has depreciated and interest rates are already high.

Luis Alberto Moreno, former president of the Inter-American Development Bank, has known Ocampo for decades. They worked together in the Gaviria administration, Moreno as development minister and Ocampo as head of agriculture. Moreno is optimistic about his former colleague’s chances of success. “He is Colombia’s most respected economist and he is perfect for Petro—not mainstream, but also not prone to doing crazy things. He will be responsible.” It remains to be seen how much change he will be able to effect.