Looking forward to the last year of Argentine President Alberto Fernández’s term, the question presents itself: How likely is it that things will go from bad to worse?

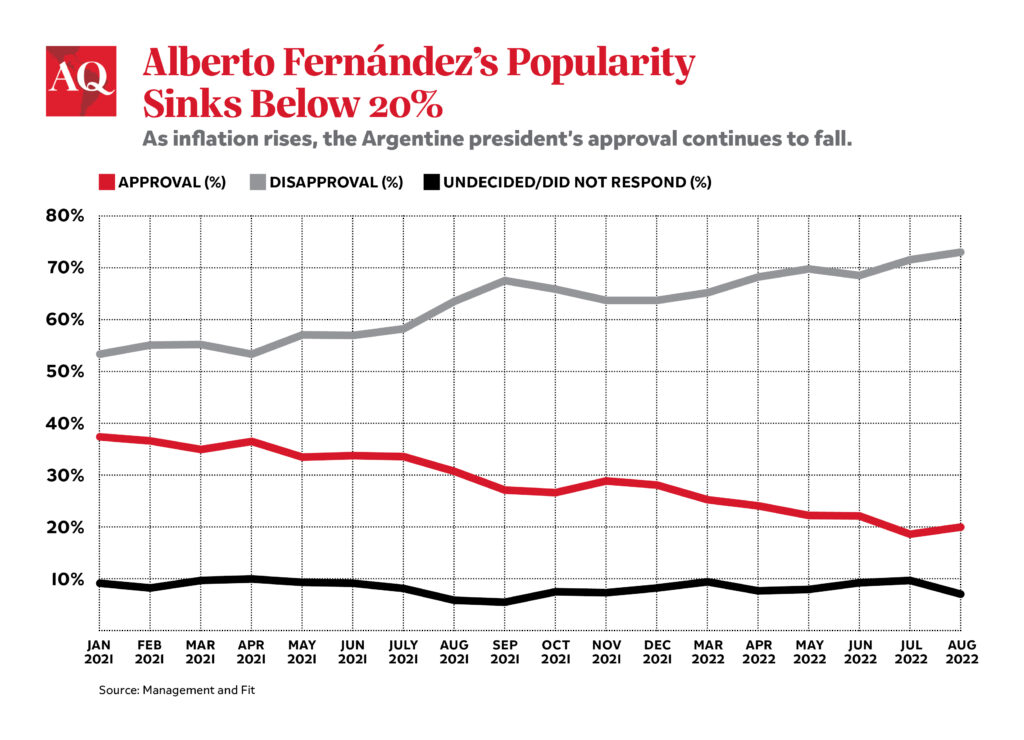

The government’s declining popularity is being compounded by skyrocketing inflation and increased social tensions that now look to be the central feature of Argentina’s political landscape. Not all of this is new, of course: Inflation and a lack of dollars are well known problems for Argentines.

But these problems have been exacerbated over the past two years by the pandemic and the government’s never-ending interventionism. The poverty rate has remained around an astonishingly high 40% threshold since Fernández took office in December 2019.

Widespread unrest still seems relatively unlikely in the short term, but the country is treading down a perilous path of instability. Several triggers—from the new economy minister’s resignation to a breakdown in a deal with the IMF—could worsen things dramatically.

Fallout from a shocking attack

The failed attempt to assassinate Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner by a far-right extremist on September 1 was the latest and most dramatic expression of this tense scenario—but it may not necessarily represent a trend of rising political violence per se.

The attack has had two main consequences for political stability. First, it slightly improved the administration’s governability conditions among the population. Episodes of violence involving charismatic leaders, such as Kirchner, tend to generate significant commotion among civil society in Latin America. Second, it will give a boost to Kirchner’s argument that corruption investigations against her are politically motivated.

The vice president’s move to rally supporters as she criticizes the investigations against her has seen the president extend an olive branch—their relationship having been marked by significant frictions in the past two years. The two leaders have identified a rare alignment of political incentives ahead of the highly uncertain 2023 elections—but they do not have an easy road ahead.

Fernández’s final card to play

As a representative of Peronism, Fernández has rarely been given the benefit of the doubt by private investors and has therefore struggled to attract the investments that are needed to put Argentina back on track.

Two changes in the economy ministry in less than a month provided fresh evidence of this—and underscored the government’s erratic approach vis-à-vis economic policymaking. In what will probably be his final credible attempt to reverse the unfavorable economic scenario, the president on July 28 appointed well-known Peronist political figure Sergio Massa—former speaker of the lower house since 2019—to head an economy ministry that has now been merged with the agriculture and production and development ministries. This has injected new political life into the administration—but has linked political stability to the success of the new minister’s agenda.

Massa’s arrival is unlikely to lead to U-turns in Argentina’s unorthodox economic platform. The minister, who ran for president in 2015 and came in third, continues to have significant electoral ambitions. In Latin America, that typically means limited appetite for far-reaching, unpopular reforms—even if they are much-needed, particularly regarding government spending.

But that doesn’t mean Massa won’t work to improve Argentina’s economic situation by gradually increasing policymaking predictability and reducing distortions related to the budgetary allocation for subsidies. He will also use the unprecedented powers of the economy ministry to improve the coordination of the government’s economic interventions. This will likely be somewhat successful in the coming months, but there is limited evidence that it will be sufficient—underlining the riskiness of Fernández’s political bet.

Borrowing political capital from his ally, Fernández has risked making himself a lame duck, with his economy minister spearheading the relevant decisions going forward, leaving the president in a secondary position and with limited chances of leading the Peronist ticket next year. Sergio Massa’s resignation, if he is unable to deliver significant results regarding the economic crisis within a few months, could worsen financial expectations further, reinforcing Argentina’s spiraling inflation trend and driving additional conflicts within the ruling coalition.

Argentina’s political minefield

A number of factors could transform limited demonstrations into widespread unrest in Argentina and set off a downward spiral in political stability.

Abrupt developments related to Fernández de Kirchner’s corruption case, including a potential presidential pardon or her imprisonment, would likely mobilize both sides of the political spectrum, fueling polarization and reducing further Argentina’s already low levels of social cohesion.

A similar scenario could also be seen in the event that inflation escalates even further—for example, surpassing three figures by the end of the year—or if the government abruptly accelerates ongoing cuts to subsidies for gas and electricity, resulting in acute popular discontent from Peronist social movements, such as labor unions.

All in all, Peronism has never been under so much pressure in terms of popular approval, which strengthens the opposition’s electoral chances for 2023. But the opposition is not without its own challenges. New fragmentation between the centrist and moderate group associated with former President Mauricio Macri (2015-19) and more radical figures, such as far-right deputy Javier Milei, means the center and right will also suffer from uncertainty. But it’s still more likely than not that one of these two groupings will retain the upper hand to beat Peronism, upsetting mainstream politics in Argentina just like Macri’s win did back in 2015.

Sergio Massa visited IMF directors on September 12, seeking to assure the Fund that Argentina would follow through on the provisions of the deal. Massa was praised by the institution and its managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, due to his appealing plans and friendly rhetoric. On September 19, the fund preliminarily unlocked $3.9 billion to help Argentina navigate the ongoing uncertainties of the current global scenario. But that doesn’t rule out the chances of an acute deterioration of the relationship if Argentina fails to meet quarterly targets, or if the government escalates its approach to negotiations.

Alone or combined, such events have the capacity to raise social anxiety to even higher levels and increase political uncertainty to unsustainable levels. Things are fragile now, but they could get far worse.

—

Brasil is a senior political risk analyst at Control Risks.

Pera is a researcher for the Political Risks Analysis team at Control Risks.