This article is adapted from AQ‘s special report on trends to watch in Latin America in 2025

During his confirmation hearing for the presidency of Brazil’s central bank, Gabriel Galípolo said with a nervous but friendly grin: “I’m sorry that I seem to have disappointed people who expected that when I got into the central bank, a big reality show with big fights and disputes would break out.”

The comment, while made partly in jest, acknowledges the very real minefield that awaits Galípolo, 42, as he moves from director of monetary policy at the bank to its top job in January.

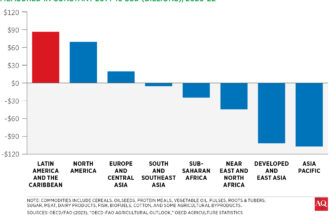

Brazil’s economic situation is delicate, as markets have reacted negatively to the government’s fiscal path. A package of spending cuts and an aggressive rate hike have failed to allay investors’ concerns. Brazil’s real will finish the year among the world’s worst-performing currencies, despite an economy that grew about 3% and other indicators like unemployment pointing in the right direction.

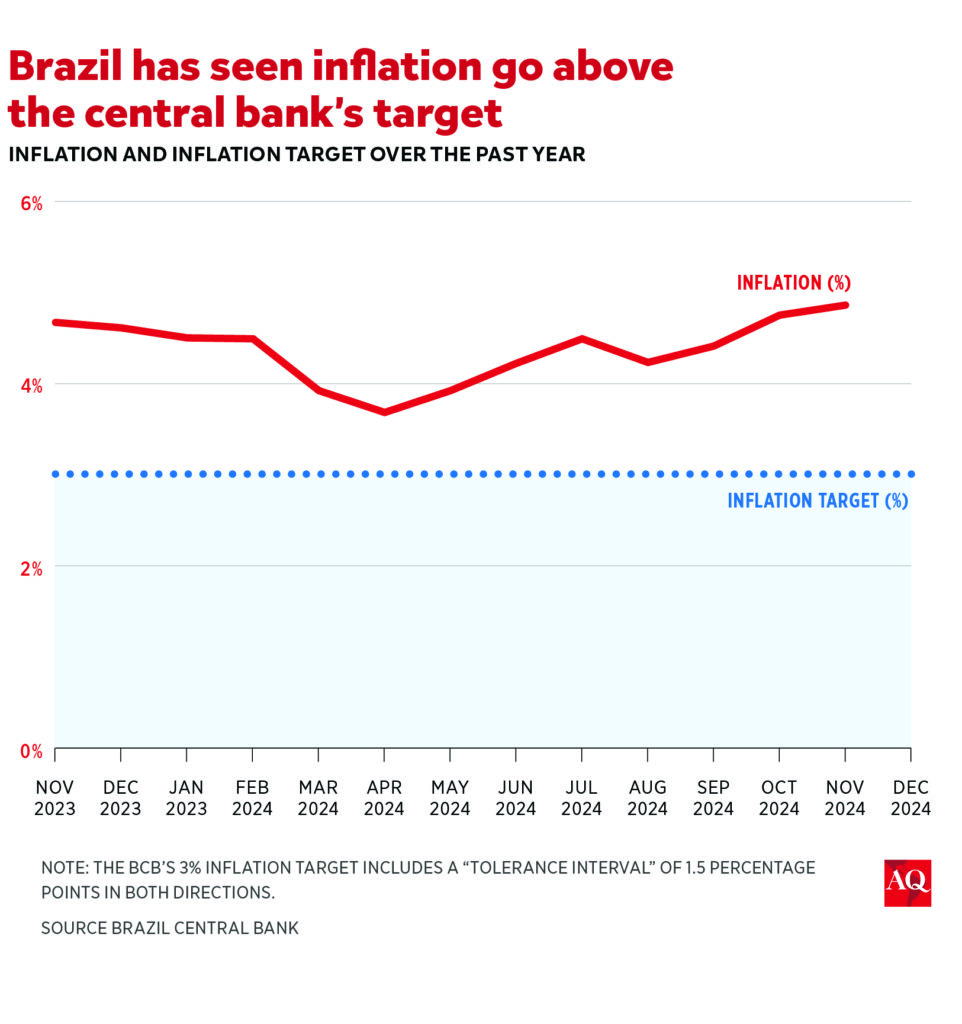

And over the past two years of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s third term in office, the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB), an autonomous body charged with keeping price increases near a 3% target, has frequently been pulled into the political fray. Inflation is currently running at 4.9%, above the top of the bank’s target range.

The government had a strained relationship with the former central bank head, Roberto Campos Neto, who was appointed by Lula’s conservative predecessor Jair Bolsonaro. In June, Lula called Campos Neto an “adversary,” accusing him of strangling economic growth and stymieing the government’s agenda with high interest rates.

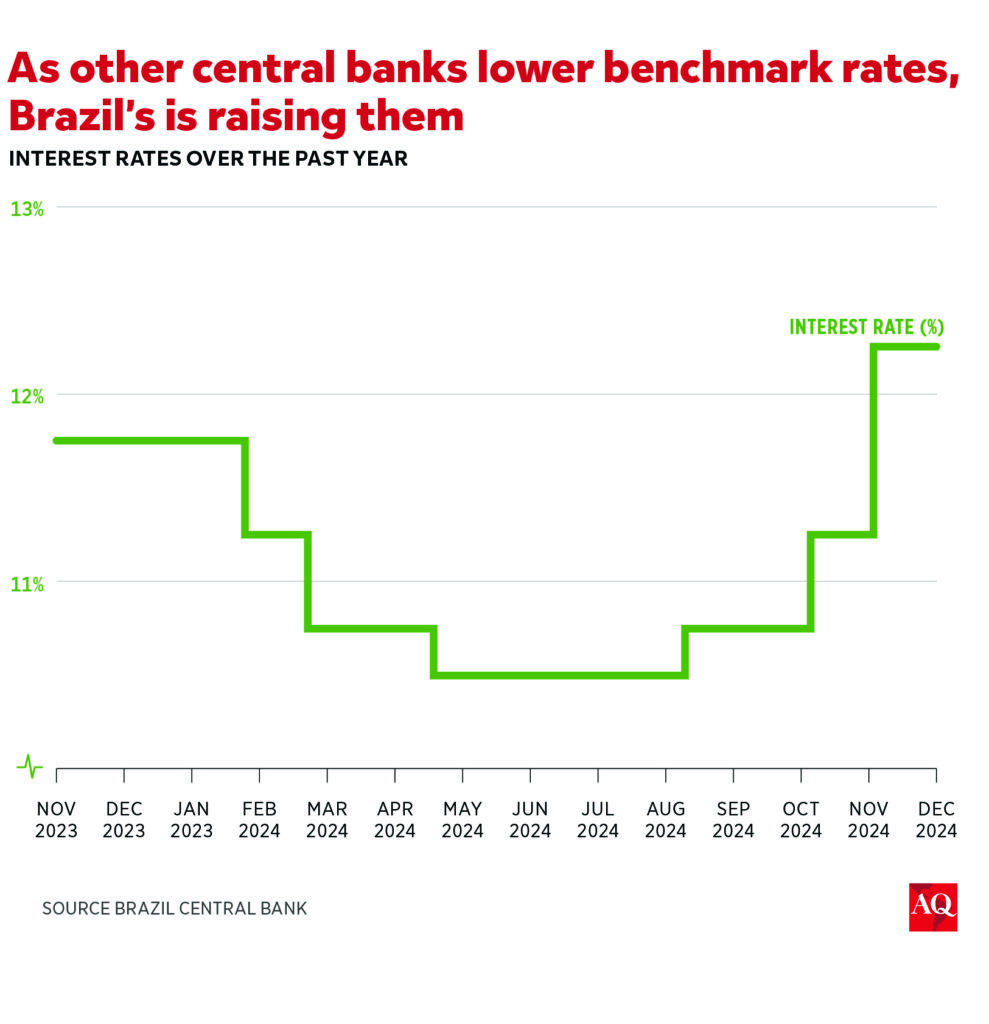

On December 11, the central bank moved aggressively against inflation, hiking interest rates by a full percentage point, to 12.25%. (Galípolo voted in favor of the decision, along with the rest of the monetary policy committee.) That’s not abnormally high by Brazil’s historical standards, but up from 10.5% in July 2024. And at a time when the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks have been cutting rates, the BCB has promised two further hikes of the same size by March, raising the prospect of further strife.

Whether anyone can navigate the tensions is unclear. But it’s hard to imagine anyone better positioned to do so than Galípolo.

Feet in two worlds

Galípolo has always operated in a space between left and right in economic debates.

He served from 2017 to 2021 as the CEO of Banco Fator, a São Paulo-based bank with about 9 billion reais (about $1.5 billion) under management and a history of working on public-private partnerships. The most important project of his tenure was the bank’s role in designing the privatization model for Rio de Janeiro’s sanitation company, Cedae.

He got his start as a student at São Paulo’s Catholic University (PUC), whose economics department follows a heterodox line—that is, one that sees a bigger role for government in the economy and often advocates for lower interest rates. He taught undergraduate courses there until 2012. Galípolo is also a close associate of Luiz Gonzaga Belluzzo, a professor and columnist for Brazil’s leading financial paper, Valor, and one of Brazil’s most influential left-wing economic thinkers, who has advocated against fiscal austerity measures and excessive deregulation of markets, arguing such policies exacerbate inequality.

But Galípolo seemed to look more favorably than many heterodox intellectuals on the private sector and was also a professor in the public-private partnerships graduate program in business administration at the São Paulo School of Sociology and Politics Foundation (FEPESP).

His career in politics also reflects his ideological complexities. It started when he was still a graduate student, in 2007, under the center-right governor of São Paulo José Serra. While working with Serra he became head of the economic advisory office for the metropolitan transport department, and in 2008 he was named director of the Project Structuring Unit of the Economy and Planning Department of the state of São Paulo. Three years later, he helped the Workers’ Party (PT) candidate for São Paulo governor draft his economic platform, strengthening his ties within that party.

During the 2022 campaign, Lula called Galípolo his “golden boy,” and tasked him with being an unofficial ambassador to financial markets, explaining each side’s concerns to the other.

It hasn’t been an easy assignment. As during his first presidency, from 2003 to 2010, Lula’s relationship with financial markets has been complicated, with government spending being a particular point of contention.

Fiscal problems have been a repeated trigger of Brazilian financial crises over the decades, including the 2014-15 recession that ultimately led to the 2016 impeachment of Dilma Rousseff. Although Lula’s government is bound by a fiscal rule that limits spending growth to 2.5%, it has boosted spending on transfers to the poor and other categories. Markets expected Brazil to close 2024 with a budget deficit in excess of 7% of GDP, one of the highest levels in Latin America.

The corresponding increase in Brazil’s public debt—which now stands at nearly 80% of GDP, and is projected to reach 97.6% by 2029—has triggered alarm in markets. Lula’s finance minister, Fernando Haddad, has been under pressure to cut or freeze government spending for 2025 and beyond in an effort to show the budget is under control. On November 28, the government announced cuts of 70 billion reais (about $11 billion) across the next two years.

Reading between the quotes

Given the fiscal pressure, markets are particularly keen to garner hints as to how independent and willing to raise rates Galípolo might be.

Galípolo repeatedly defended a low interest rate policy in his past writings, and at a central bank board meeting in May, he sided with the other Lula-appointed bank directors in favor of a larger rate cut. That decision provoked a market uproar, and since then he, along with all other members of the board, has voted in favor of hiking rates.

Since his nomination for the lead office in August, Galípolo has signaled he is willing to take a more hawkish approach. He has acknowledged a change of heart. “People in academia or market actors have greater freedom to develop theses and make bets. But the central bank’s position is always to be more conservative,” he said at an event sponsored by Brazilian bank Itaú BBA.

Given his recent statements, markets have mostly taken Galípolo’s appointment in stride.

“Since his time in the finance ministry, we didn’t feel investors were spooked because of his time as head of Fator. He was there for a long enough time and his tenure was considered successful, so since the beginning he was seen as the person who would build this bridge between (Finance Minister Fernando) Haddad’s team and markets,” Rodrigo Russo, a partner at Control Risks, a consultancy firm whose clients include investors and businesses, told AQ.

Galípolo also seems to have Lula’s backing—at least for now.

“Look, if Galípolo comes to me one day and says, ‘Hey, we have to raise the rate,’ that’s great,” Lula said in an interview in August. “If they have to go up then they have to go up.”

In fact, Lula’s dispute may have been more with Campos Neto himself than with his decisions on interest rates. Campos Neto wore a green and yellow shirt to vote in the 2022 elections, a gesture that signifies support for the right in today’s Brazil. He also raised eyebrows on the left after being the honoree at a dinner party hosted by the current governor of São Paulo Tarcísio de Freitas, a Bolsonaro ally.

Nevertheless, Galípolo himself has always maintained a good relationship with Campos Neto, and the former head of the central bank held a symbolic event on December 19 to commemorate the hand-off.

But the continued skepticism of Brazilian markets, and global factors, may make it hard for Galípolo to realize Lula’s clear vision of bringing down rates over time. Tariffs and tax cuts in the U.S. under incoming President-elect Donald Trump are expected to drive interest on U.S. government debt higher, causing the dollar to appreciate and adding to upward pressure on interest rates in other countries.

“Central banks in other countries have no way to avoid pressure coming from higher interest rates” in the U.S., Otaviano Canuto, former World Bank vice president and fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, told AQ. “Either countries in South America raise interest rates or they lose money.”

Playing a long game

It seems inevitable that sooner or later, as BCB president Galípolo will have to disappoint someone—whether it’s markets and his contacts in the financial world, or Lula and his allies in the Workers’ Party.

One possibility is that Lula understands that efforts must be made to calm markets now in order to secure important gains later. That would fit with the effort to rein in Brazil’s public spending currently being led by Finance Minister Haddad, perceived as a more moderate, relatively more business-friendly force within the Workers’ Party.

“Galípolo comes with Haddad’s support. And what’s going on at the central bank reflects a tension inside the government more broadly between different factions inside the Workers’ Party. And at the end of the day, in that debate, Lula has often sided with the economic team, betting on Haddad,” said Russo.

Galípolo may also establish credibility with financial markets now so that, if conditions allow, he may be able to lower rates before the next presidential election in 2026. That could boost short-term growth and let the government spend more, putting wind in its sails. That’s far from a sure thing. In the meantime, it boils down to yet another balancing act from Galípolo—a skill in which he has practice.

Franco is an editor, writer and podcast producer at AQ.

Burns is an editor at AQ.