When Argentina’s economy collapsed in late 2001, everybody was absolutely sure whose fault it was. Aloof, hermetic and increasingly prone to slurring his words in public, President Fernando de la Rúa had managed to trash the government’s fiscal accounts in just two years in power. Steakhouses and nightclubs were empty, unemployment was nearing 20 percent and cash was so scarce that much of the economy reverted to the barter system – trading haircuts for groceries, family heirlooms for rent. As Christmas approached, looting broke out at supermarkets and anti-government protests turned violent. Finally, on the evening of December 20, De la Rúa hand-wrote a resignation letter, muttered something to his secretary about collecting the soaps from his private bathroom, climbed the stairs to the palace roof and flew away in a helicopter.

Perfect, Argentines said. Now we can get out of this mess. But the next president was so overwhelmed by the challenge that he quit too, setting off a chain reaction that would ultimately see five different presidents in only two weeks. Appalled, Argentine protesters adopted a new slogan – ¡Que se vayan todos! or “They all must go!” Banging pots and pans, millions took to the streets to demand that the entire political class – the president, Congress, everybody – step aside to allow for a top-to-bottom renewal.

Fast-forward 15 years, and Brazil is now having a similar moment. The economy is not as bad as Argentina’s was, and nobody has yet boarded any helicopters. But the Brazilian public appears to be arriving at the same conclusion – that nobody currently on the political stage is competent or clean enough to address the enormous crises facing the country.

As recently as 10 days ago, it looked like the country had settled on a solution: To impeach President Dilma Rousseff and hand power to her vice president, Michel Temer. A nationwide poll showed that 68 percent of Brazilians supported impeachment, and millions rallied in the streets to demand just that. Smelling blood, Temer’s Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) held a news conference to announce it was breaking with Rousseff. The PMDB’s leaders thrust their hands in the air, chanted “Dilma out!” and began openly speaking about the economic agenda for a future Temer government.

But the coming-out party backfired – and how. The sight of figures like Eduardo Cunha, a legislator who faces multiple corruption charges, reminded everyone that several of the PMDB’s leaders are arguably just as tainted as Rousseff by the scandals and economic mismanagement of recent years. The ensuing national mood was best captured by, of all people, a Supreme Court justice caught unaware by an open microphone. “My God in heaven, is that the only other choice we have for a government?” Justice Luís Roberto Barroso was overheard marveling to a group of students. “There’s nowhere to run. This is a disaster.”

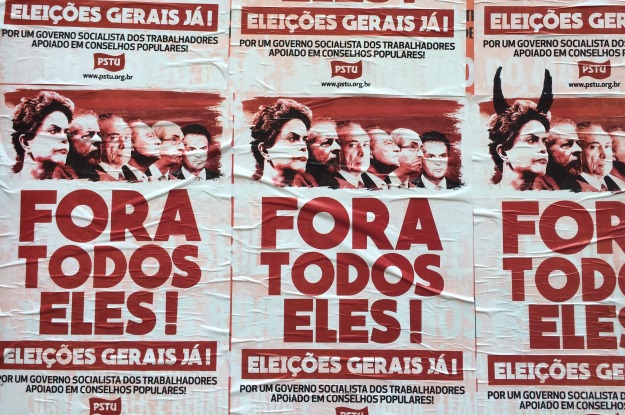

I’ve been back in Brazil for the last week, and if there’s one consensus right now, that’s it. At a protest on São Paulo’s Avenida Paulista last Friday night, the rallying cry was “Fora Todos Eles!”, a near-verbatim facsimile of the Argentine slogan from 2001-03. One young protester held up an image of all of Brazil’s prominent politicians from both left and right – Rousseff, Temer, Cunha, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and opposition presidential hopeful Aécio Neves – and then tore it in half with a primal scream, drawing raucous cheers from the crowd. On Sunday, Folha de S.Paulo, the country’s biggest newspaper, published an editorial entitled “Neither Dilma nor Temer,” calling on both to resign. Some in Brazilian political and business circles are starting to whisper that, given the absence of any clear leadership, it could take as long as a decade for the economy to fully recover.

—

It’s jarring to hear such pessimism here, because people who bet against Brazil in the long run have tended to lose. Indeed, for all the hoary talk over the years about “the country of the future that always will be,” from 1900 to 1980 only Japan’s gross domestic product grew more than Brazil’s among major economies. The last two decades have seen tremendous advances as well. Rough stretches such as 1992-93, 2002 and 2008 have all passed more quickly and painlessly than most expected. Moderate, resilient growth seems to be Brazil’s natural state.

Yet, if you plot out the various paths forward, things do get bleak pretty fast.

For starters, it’s still entirely possible that Rousseff will manage to serve out her term through New Year’s Day 2019. Despite the fantasies of local and foreign editorial boards alike, Rousseff will never resign – she has been telling aides that previous Brazilian presidents who were ousted, namely Getúlio Vargas and João Goulart, surrendered far too easily. Meanwhile, since Lula effectively assumed day-to-day control of Rousseff’s government last month, he has been able to slow the exodus of allies from the government’s coalition. This loyalty has come at a price: Estado de S.Paulo reported this week that the government has abandoned its modest fiscal targets in favor of funding pork-barrel projects for friendly legislators and avoiding unpopular tax hikes. If true, the price will be higher inflation – and an even more distant economic recovery.

As for impeachment… Rousseff and her Workers’ Party have indignantly denounced the process as a “coup,” comparing today’s Brazil to the last military putsch in 1964. But the proper analogy may actually be 1998. That was the year the U.S. House of Representatives voted to impeach President Bill Clinton for perjury related to an affair with a White House intern. Was that a coup? No. Was it a pretty flimsy reason to impeach a democratically elected president? Yes.

Everyone has marveled at the massive corruption at Petrobras under Rousseff’s watch, and the weight of evidence accumulated by Judge Sérgio Moro and his team. Prosecutors say they have proof that dirty Petrobras money was used to finance Rousseff’s narrow reelection victory in 2014. Ah, you might say, that seems like a pretty good reason to impeach somebody! But of course, the case being used against Rousseff has absolutely nothing to do with Petrobras and the 2014 election. Instead, it centers on accounting tricks Rousseff used to meet budget targets – tactics that were also used, although to a far lesser extent, by her predecessors. Why build the case around this? Because if it were about dirty campaign funds, the PMDB would probably fall too – since Temer was Rousseff’s running mate.

Up until last week, people seemed willing to tolerate whatever games Brasília wanted to play, as long as they ended with Rousseff gone. But after the PMDB’s botched public pow-wow, it was as if the whole country peered into the abyss and said – “Wait, are we really sure we want to do this? Under these circumstances? For these guys?” It’s no accident that since then, impeachment has lost much of its momentum – every reliable tally, both private and public, currently shows the opposition well short of the votes it needs.

Even if impeachment proceeds, it now seems a Temer government won’t be the panacea many investors were hoping for. Fixing Brazil’s economy is actually pretty straightforward – it will require austerity, an opening to trade, and a war against the bureaucracy stifling small and large businesses alike. But all of these measures will be unpopular in the short term. And anything less than a clean impeachment will fuel the unions, social movements and legislators who will be crying “coup” from day one of a Temer government, and opposing every “cruel” or “neoliberal” measure he proposes. Meanwhile, Temer is in a position of weakness before he even starts. Polls show just 16 percent of Brazilians expect good things if he becomes president. He could always surprise, of course. But it seems like a recipe for a weak government that will struggle to marshal consensus behind any reforms, and will mostly just be limping ahead to 2018. Which sounds an awful lot like Brazil today.

—

So, meu Deus do céu, where does this go from here?

In the short term, frankly, it’s anybody’s guess. The daily back-and-forth, including Tuesday’s Supreme Court order to start impeachment proceedings against Temer, is exhausting. At this time of chaos, though, I try to remember one thing: Don’t bet against Lava Jato, as the investigation of Petrobras is known. The constant flow of damning evidence has shown no sign of letting up – prosecutors say they’re just 30 percent done with the case. If that’s true, then it still seems likely this government will fall under the weight of the allegations. Whether that’s via impeachment, or the process known as cassação that would remove both Rousseff and Temer, or the newest idea floating around in Brasília, for Congress to call new elections… whoever says they know is either lying or wrong.

In the long term, though, the outcome seems clearer. The anger and despair in Brazilian society over the worst recession in 80 years is being directed at not one or two leaders or parties, but at the entire political class. When the next election comes, whether it’s in 2016 or 2018, it will almost certainly be a ¡Que se vayan todos! kind of vote. In Argentina, that produced a little-known governor from Patagonia named Néstor Kirchner, who won the presidency with just 22 percent of the vote. In Brazil, it could be anyone from a cast of anti-establishment figures that includes environmentalist Marina Silva, former minister Ciro Gomes, Jair Bolsonaro of the right-wing “Bullets, Bible and Beef” Caucus, or somebody entirely new. History says Brazil will move on to its next phase, bounce back quickly, and resume its forward march. But, yes – it requires an awful lot of faith to believe that right now.

—

Winter is editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly