After more than a decade studying Brazil, there are still two things whose popularity I cannot fully explain: bacalhau and the PMDB.

The former is a vile salted codfish that no human being should ever be forced to ingest. The latter is the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, a shape-shifting, ideologically diverse group of politicians that for the last 20 years has unabashedly supported whomever is president in order to “help govern” Brazil, and also reap pork-barrel spending and other “patronage” along the way.

Despite this lack of a clear brand (or perhaps because of it), the PMDB is the second-largest party in Congress and the key partner in President Dilma Rousseff’s ruling coalition. If the PMDB abandons ship in the next few weeks, as many now expect following Sunday’s massive anti-government protests, Rousseff’s presidency may well be finished by August, the victim of either impeachment or the more complex process known as cassação. Depending on how the crisis plays out, the PMDB could end up with the presidency for itself. But the party’s unique identity also explains why, even in that scenario, challenging days would still lie ahead for Brazil.

The PMDB’s key role in today’s crisis has its roots in Brazil’s last dictatorship, when it was the only officially tolerated opposition force. Led by towering, compromise-minded statesmen such as Tancredo Neves and Ulysses Guimarães, the PMDB pressured the generals for a return to full democracy in the 1980s while not backing them into a corner, a deft balancing act whose benefits can still be felt today.

In ensuing years, the PMDB became too polymorphous for many of its members, leading Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Miguel Arraes and others to join different parties or found new ones. What was left of the PMDB has often seemed interested in power primarily for power’s sake. When I arrived in Brazil as a reporter in 2010, I was shocked by how openly the party demanded its rewards for helping Rousseff win the presidency – and how everyone (including the press) treated this as completely normal. The PMDB was “ceded” critical ministries such as Agriculture and Tourism based not on whether they had qualified people to lead them, but whether their operating budgets were big enough to satisfy party bosses. OK, some of this happens in coalition governments the world over – but let’s just say that when two PMDB ministers were caught allegedly skimming money or favors during Rousseff’s first year in office, no one was genuinely surprised. (Other parties faced similar accusations.)

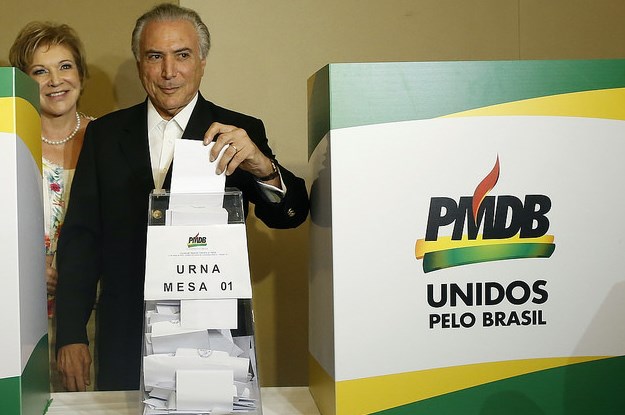

Today, the PMDB’s public image continues to be defined by shady characters such as Eduardo Cunha, the speaker of Congress’ lower house, who faces multiple corruption charges and has employed every trick possible, including outright blackmail, to try to wriggle off the hook. Yet it’s also true that the party is not a monolith; it has a coterie of genuinely bright, competent leaders. Meanwhile – and this is critical to understanding the PMDB’s behavior right now – many of its graying leaders continue to see the party in its original light, as the one true guardian of Brazilian democracy. Elders such as Moreira Franco (71), Nelson Jobim (69) and Michel Temer (75), Rousseff’s vice president, have made long careers out of presenting themselves as above the partisan fray, meeting regularly with business leaders and opposition legislators alike to help define and advance what they see as the Brazilian establishment’s best long-term interests.

In other words, if there’s a smoke-filled room in Brasilia or São Paulo, the PMDB is usually holding many, if not most, of the cigars. Well, there are plenty of smoke-filled rooms in Brazil these days. And there is ample reason to believe that, over the past two weeks, the elite have finally made the decision to break with Rousseff and her Workers’ Party, and perhaps let Temer and the PMDB try their own luck in power.

—

For those unfamiliar with the PMDB’s history, its behavior in recent days has appeared incomprehensible. On Saturday, party leaders gathered in Brasilia to decide whether to formally leave Rousseff’s governing coalition. At first, there didn’t seem to be much suspense. Raucous party operatives chanted “Dilma out!” One congressman was quoted saying “not a single leader spoke in favor of the government, (not) even the ministers in the Cabinet.” Another declared: “This government will fall. It cannot survive. Either we abandon ship now, or go down with it.”

So, some were mystified when the PMDB decided not to break with Rousseff – and instead postpone its decision by 30 days. In reality, though, this was totally consistent with the old guard’s self-image; how could the guarantors of Brazilian governability be the ones to give the president the final push into the abyss? Channeling the party’s magnanimous 1980s-era caciques, Temer told the deflated crowd: “This is not the time to divide Brazilians … This is the time to build bridges.” Whether he actually believed this or not, the truth is that the PMDB was merely stalling, waiting for someone else to give Rousseff a shove.

The next day, more than 1 million Brazilians happily obliged. They took to the streets in even larger numbers than expected to demand her removal from office, and voice support for Judge Sérgio Moro’s sweeping anti-corruption investigation at Petrobras. As a referendum on the national mood, Sunday wasn’t perfect – the working class was conspicuously absent, and protesters were once again wealthier than average Brazilians, polls showed. Judging Rousseff’s popularity based on downtown São Paulo, where demonstrations were by far the biggest, is like judging Barack Obama’s popularity based on rural Mississippi. But if Brazil’s political class were waiting for an excuse to usher the crisis into its endgame, they certainly got it, in spades. Reuters’ Anthony Boadle reported on Monday, citing three senior PMDB officials, that the protests have finally convinced the party leadership to support impeachment. Many vote-counting outfits believe that, with the PMDB on their side, the opposition will be able to muster the two-thirds of votes necessary in the lower house to move impeachment proceedings to the Senate.

There are several political reasons, and also a more cynical one, for the PMDB to move forward now. In late 2015, when the party last seriously considered impeachment, it concluded there wasn’t a compelling enough case against Rousseff, and that the economy could conceivably recover by the end of 2016. The financial establishment concurred, and the drums of impeachment died down. Today, while there is still no suggestion of criminal wrongdoing by Rousseff herself, prosecutors have compiled what they describe as clear proof her party filled its coffers with dirty money. The constant flow of plea bargain testimony and new arrests suggests more damning evidence is on the way. Meanwhile, the economy remains stuck in its death spiral, with 100,000 Brazilians losing their jobs every month and no hope of recovery until 2017 or even later. The business community is betting that Temer, who would serve out Rousseff’s presidency if she is impeached, would draw on the PMDB’s old traditions to begin healing the country, stabilize the economy – and marshal some pro-business reforms through Congress.

This leads to the PMDB’s more cynical calculation: If it doesn’t act now, it may well get dragged down, too. Under the other potential outcome to the crisis, cassação, an electoral court would invalidate the Rousseff-Temer ticket’s 2014 reelection victory – which would in turn remove both of them from office, and result in new elections within 90 days. So, would impeaching Rousseff save Temer and the PMDB? Here, things get really murky. Aécio Neves, the opposition’s leader, denied in a newspaper interview published today that there is a deal to protect the PMDB in return for their support for impeachment. In fact, Neves said it isn’t even possible, since the electoral court is politically independent. He may be right, but three words keep popping into my head: smoke-filled room. It seems unlikely that the elite would go through the trauma of impeachment, and then allow Rousseff’s replacement to be booted out in short order. That’s not typically how they roll.

Brazil’s establishment has effectively concluded that at this point anybody would be better than Rousseff and the Workers’ Party. Yet Temer and the PMDB are, for the moment, their preferred solution – they offer the security of the old political guard, without the uncertainty of a new election and the outsider(s) it might bring. The question is: Will the Brazilian people agree, once the euphoria of impeachment has passed? Will a populace that is absolutely fed up with corruption and business as usual in Brasilia throw their support behind the PMDB, the ultimate old-school party? Will Temer have the political capital he needs to stabilize the economy, while fending off an angry and disenfranchised Workers’ Party and its supporters? Whatever happens, one thing is certain – it’s easier to “help govern” than to “govern.” That’s a lesson the PMDB knows better than anybody.

—

Winter is editor in chief of Americas Quarterly