In the two years since he took office, Colombian President Gustavo Petro has riled U.S.-Colombian relations, chipping away at nearly a quarter century of steady U.S. bipartisan support. It should not surprise that the nation’s first leftist president would seek to shake things up both internally and in the global arena. But Petro’s rhetoric and positions on issues such as counternarcotics, peace, and security—the centerpieces of collaboration over five U.S. and Colombian administrations—have alienated core constituencies in the U.S. Congress and even among some in the Biden administration.

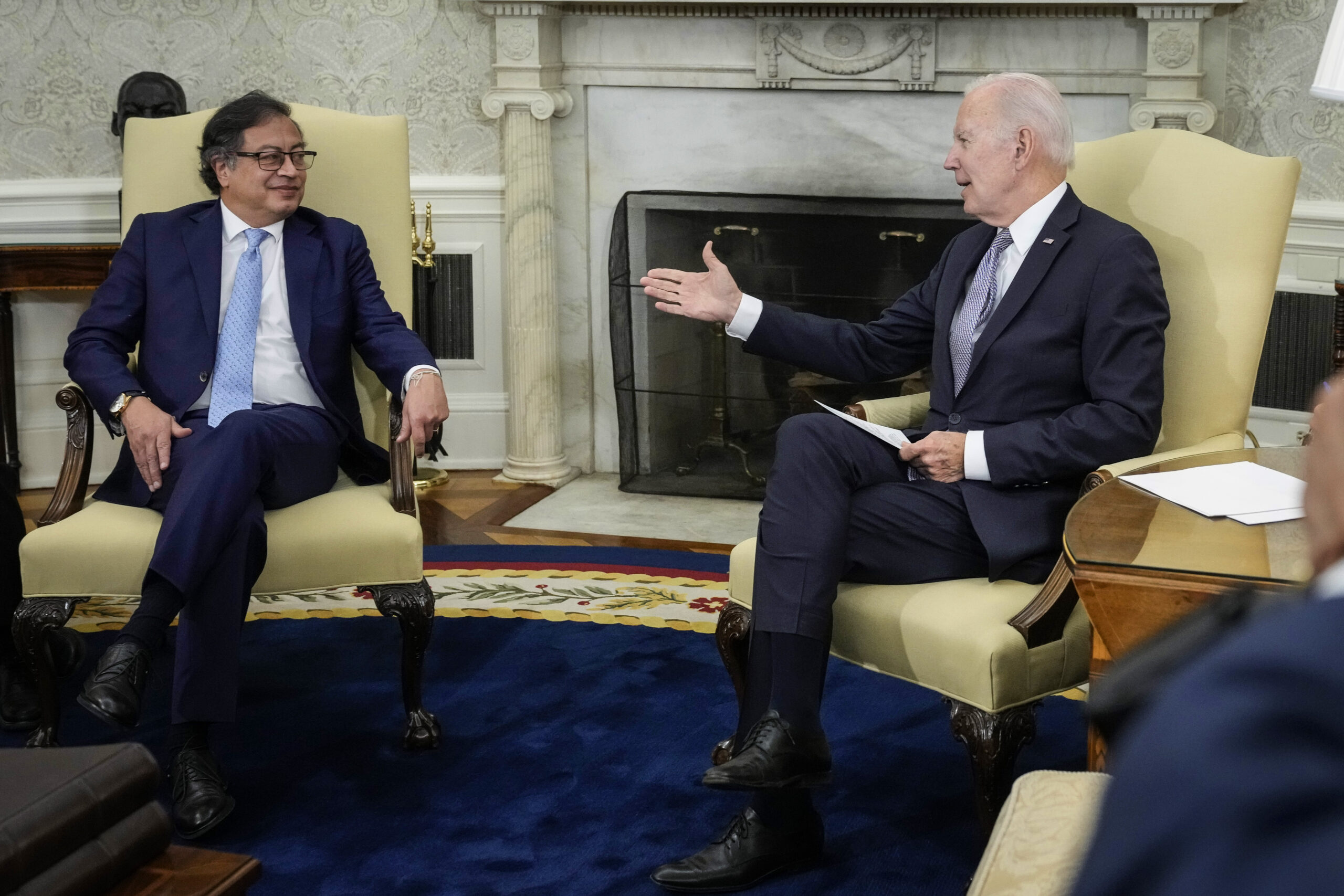

To be sure, there are strong institutionalists across the U.S. government who see Colombia, the country—not any particular government—as a long-term vital ally and strategic partner. President Joe Biden articulated this view in an April 2023 White House meeting with Petro, calling Colombia “the key to the hemisphere.” No daylight emerged between Biden and Petro on the latter’s priorities: fighting climate change and reducing reliance on fossil fuels, fostering ethnic and gender inclusion, and bringing development and security to neglected areas of the Colombian countryside.

More recently, other senior officials emphasized Colombia’s centrality to U.S. interests. Chargé D’Affaires Francisco Palmieri told a business gathering in May that “Colombia continues to be the best ally and strategic partner of the United States in Latin America.” That month, the head of U.S. Southern Command, General Laura Richardson, praised the strong and enduring “mil-to-mil” relationship forged over decades of close institutional collaboration.

But in public and private, another group of U.S. officials—call them “the disillusioned” or even “the rejectionists”—express alarm over the direction of the Petro government’s policies, wondering if U.S. resources wouldn’t be better spent addressing crises in Ecuador and Haiti at a time of overall U.S. budget constraints. That said, perceptions about Petro may shift in a positive direction if he helps secure a democratic solution in Venezuela following the massive electoral fraud of July 28.

Divisions over counternarcotics

The biggest rift that has emerged is over counternarcotics policy, long the central driver of U.S. involvement in Colombia. Past U.S. administrations have tried to “de-narcotize” bilateral relations— trade and investment, for example, have boomed since the signing of a bilateral free trade agreement in 2012—one that Petro has vowed to renegotiate, so far without much traction.

Colombia continues to be the source of roughly 90% of the cocaine entering the United States. This figure has been unchanged since 1999 when policymakers launched the massive assistance program known as Plan Colombia. The emphasis of U.S. counternarcotics policy has shifted to synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, now responsible for the majority of overdose deaths in the U.S. But cocaine remains a priority—it is a delivery mechanism for fentanyl, increasing its lethality and abuse.

The Petro government’s 2023 National Drug Policy shifts attention away from the lowest level of the drug supply chain—campesinos who grow coca leaf—to the more lucrative stages of cocaine processing, export, and money laundering.

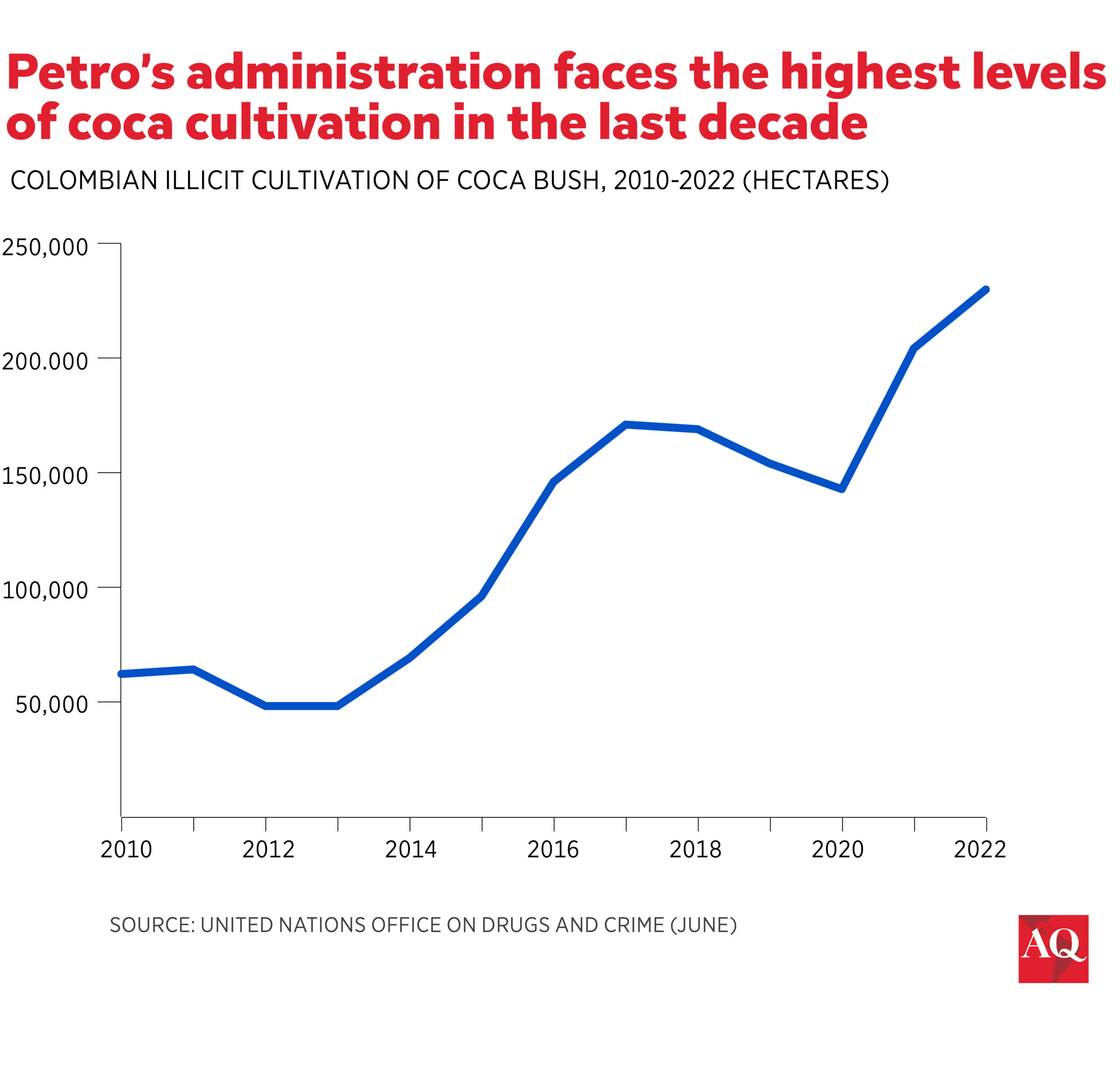

The difficulty is that coca cultivation has surged, a trend that began before Petro’s presidency but has now reached historic levels. In its most recent report, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) put coca cultivation at over 230,000 hectares, a 13% increase between 2021 and 2022 and nearly a five-fold jump since 2013. More alarming, the UN noted that potential cocaine output rose 23.4% from 2021-22, reaching an all-time high of 1,728 metric tons.

Last month, a Bogotá-based UNODC official decried a “truly expansive phase” of global cocaine markets, with demand rising in Europe and new markets appearing in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Colombia’s cocaine boom has worsened security crises elsewhere in South America, nowhere more so than in neighboring Ecuador. There, according to the UN, “the increased trafficking of cocaine from Colombia has resulted in a wave of lethal violence linked to local and transnational crime groups.”

Colombian officials counter that drug seizures and the destruction of cocaine laboratories rose in 2023, with more dramatic increases so far this year. Some U.S. officials agree. But others are more skeptical, maintaining that cocaine interdiction has risen because so much more cocaine is being produced. Moreover, the dialing back of coca eradication removes a penalty for growing coca, even as prices for the leaf have plummeted amidst a glut and changes in the purchasing patterns of drug traffickers.

In a rebuke to the Petro government and the Biden administration, the Republican-controlled House voted in June to slash next year’s aid allocation by a whopping 50%, a historic cut. (Only military sales financing was funded in full). In addition, and in a first for Colombia, the House required the State Department to report on “how [the] Government’s current policies align with United States national interests” on drug trafficking, migration, and other issues. The bill subjects counternarcotics aid to a 30% cut unless the State Department “certifies” that Colombia has “reduced overall cultivation, production, and drug trafficking” and continues cooperation on extradition and other counternarcotics issues. (Extradition cooperation has not diminished).

These House provisions are unlikely to become law: the relevant committee in the Democrat-controlled Senate approved more aid, and the full Senate has yet to take up the bill. However, actions in the House indicate strong disapproval, foreshadowing how policy might shift if Donald Trump wins the November election.

The security issue

Another area of broad U.S. and international concern is the deterioration of security in many rural areas of Colombia. The 2016 peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), Colombia’s largest guerrilla group, set off a wave of violent competition among remaining insurgent and criminal groups over territory and drug trafficking routes. Petro once campaigned in favor of implementing the 2016 peace agreement, and in June, the UN praised advances in planning and inter-agency coordination. But frustrated implementers claim the 2016 accord has ceased to be a priority. Instead, they say, the government is focused on multiple negotiations with remaining armed groups under the rubric of Paz Total, Total Peace.

Achievements in the talks are scant. On-again, off-again ceasefires have allowed groups to consolidate and expand their control, creating rifts within the Petro administration itself. The government’s decision-making process—decried by close observers as improvised and lacking clear objectives—has left the civilian population unprotected, quite the opposite of Paz Total’s goal.

Since 1999, the U.S. government has provided nearly $14 billion under Plan Colombia, Peace Colombia, and successive strategies. At a time of shrinking appetites for foreign aid and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, it is perhaps unsurprising that financial support for Colombia is diminishing. The question for the long term is whether Petro’s rocky presidency marks a pivot away from close U.S.-Colombian relations or whether institutionalists in both capitals hold firm as new presidents take office in the United States and Colombia in 2025 and 2026, respectively.