NEUQUÉN, Argentina — Like the dog that didn’t bark in the famous Sherlock Holmes story, the most notable events of Argentine economy minister Sergio Massa’s first 100 days in office might be the ones that did not occur.

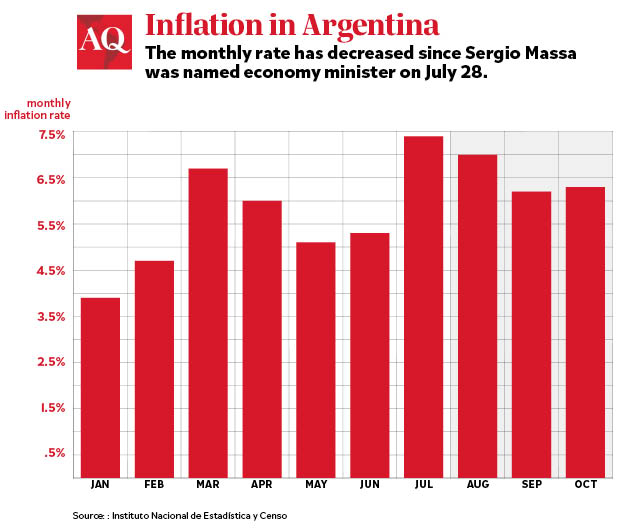

High inflation did not become hyperinflation. Argentine foreign reserves were not completely depleted. The political crisis did not escalate. The country did not default on the IMF deal signed in March 2022. The core group of kirchneristas did not leave the government in revolt. None of these things were certain at the end of July, when Massa replaced the short-lived Silvina Batakis at the head of the economy ministry.

The three-month tenure for the veteran Peronist moderate and lawyer by training might not seem like a great achievement, but he deserves some credit simply for lasting this long. And he’s done more than that: He has given the ruling Frente de Todos coalition the shot in the arm it needed to reach 2023 still on its feet. Not a lot—and yet, plenty.

The Massa months

Massa’s ascent to the economy ministry was the outcome of a months-long and very public tug-of-war between President Alberto Fernández and Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner over the direction of economic policy. Both realized that the uncertainty created by their strife diminished their political prospects and threatened their government’s survival. The solution to the impasse was to bring the third and more junior partner in their coalition, Massa, into a position of greater responsibility.

The two Fernándezes agreed to give Massa power over economic policy, including areas such as energy, industrial production, the relationship with the IMF and external credit—a portfolio broader than that of any economy minister since Néstor Kirchner’s first economy minister, Roberto Lavagna.

But Massa has not used his power to make radical shifts. He did not go either for a redistributive shock, as some had hoped, nor for an adjustment shock, as others had feared. (The former would have entailed nominal wage increases and price controls; the latter, lifting currency controls, privatizations and massive public-sector layoffs.) Instead, he has focused his messaging on Argentina’s natural resources, touting its opportunity to become a source of “energy, proteins and minerals” for the world. His attempt to project authority and decisiveness has been combined with an attempt to build an alliance with the industrial sector, with generous pro-industry regulations. In the process, he has won admirers in the U.S.

But he has also shown he has no qualms about making the kind of economic intervention that kirchnerismo has long been known for—such as a deal with the private sector to freeze prices for more than 1,400 goods, mostly foodstuffs and other staples, announced on November 10. In short, Massa’s first few months were spent performing a balancing act between left and right, interventionism and laissez-faire.

Massa is not an economist, and he does not speak like one. He is, first and foremost, a politician. However, and maybe counterintuitively, this has served him well in these few months because the main problems of the Frente de Todos government are political. The government has been divided into two factions, neither powerful enough to act unilaterally, but both powerful enough to block the other. The result has been paralysis and indecision. What Massa brings to the table is not some kind of radical economic vision, but the power to make decisions and to see them through.

What does Massa want?

Questions remain over Massa’s endgame. Is he going to run for president in 2023? Despite all the recent attention, he has remained a somewhat mysterious figure. On the one hand, Massa is an old-school political man, for whom public service has been a full-time job since his twenties—from local council aide, to mayor of the city of Tigre, to speaker of the lower house.

Massa has never been shy about his political ambitions (he ran for president in 2015 and finished third in the first round). It is hard to imagine that he would accept the challenge of steering the Argentine economy if he was not at least thinking about the presidency.

On the other hand, as any good politician must, he is good at dodging uncomfortable questions. In particular, he has been reluctant to say whether he is planning on running for president in 2023. In late October he claimed that his children did not want him to run, and that he would look at next year’s election “from afar.” Such reticence might be understandable, given that any viable route to the presidency depends on two factors. The first is Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who still retains the power of blocking or facilitating any nomination.

The second is inflation. Massa can be credited with preventing price increases from reaching hyperinflation levels, but he hasn’t brought it down—the monthly rate was 6.3% in October, after hitting a similar level in September. His presidential chances hinge on that number more than anything else. If he brings it down, even by something like 20% annually, he has a chance—if not, he will look at next year’s election from afar. Three months have passed, and little more than 11 remain.

—

Casullo is a political scientist and professor at the National University of Río Negro