It’s the question in Washington that won’t go away: “Is Lula anti-American?” Since returning to Brazil’s presidency on January 1, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has repeatedly caused alarm in the U.S. capital and elsewhere with his comments on Ukraine, Venezuela, the dollar and other key issues. An unconfirmed GloboNews report in June said President Joe Biden may have abandoned any intentions of visiting Brasilia before the end of the year because of frustration with Lula’s positions.

The question causes many to roll their eyes, and with good reason. Three decades after the end of the Cold War, some in the United States continue to see Latin America in “You’re either with us or against us” terms. Washington has a long record of getting upset with Brazil’s independent stances on everything from generic AIDS drugs in the 1990s to trade negotiations in the 2000s and the Edward Snowden affair in the 2010s. A large Latin American country confidently operating in its own national interest, neither allied with nor totally against the United States, simply does not compute for some in Washington, and maybe it never will.

That said, there is a long list of reasonable people in places like the White House and State Department, in think tanks and in the business world who are perfectly capable of understanding nuance — and have still perceived a threat from Lula’s foreign policy in this, his third term. The list of perceived transgressions is long and growing: Lula has repeatedly echoed Russian positions on Ukraine, saying both countries share equal responsibility for the war. In April, Lula said blame for continued hostilities laid “above all” with countries who are providing arms—a slap at the United States and Europe, delivered while on a trip to China, no less. Lula has worked to revive the defunct UNASUR bloc, whose explicit purpose was to counter U.S. influence in South America. He has repeatedly urged countries to shun the U.S. dollar as a mechanism for trade when possible, voicing support for new alternatives including a common currency with Argentina or its other neighbors. Lula has been bitterly critical of U.S. sanctions against Venezuela–”worse than a war,” he has said—while downplaying the repression, torture and other human rights abuses committed by the dictatorship itself.

For some observers, the inescapable conclusion is that Lula’s foreign policy is not neutral or “non-aligned,” but overtly friendly to Russia and China and hostile to the United States. This has been a particular letdown for many in the Democratic Party who briefly saw Lula as a hero of democracy and natural ally after he, too, defeated an authoritarian, election-denying menace on the far right. And for the record, it’s not just Americans who feel this way: the left-leaning French newspaper Liberation, in a front-page editorial prior to Lula’s visit to Paris in June, called him a “faux friend” of the West.

To paraphrase the old saying, it’s impossible to know what truly lurks in the hearts of men. But as someone who has tried to understand Lula for the past 20 years, with admittedly mixed results, let me give my best evaluation of what’s really happening: Lula may not be anti-U.S. in the traditional sense, but he is definitely anti-U.S. hegemony, and he is more willing than before to do something about it.

That is, Lula and his foreign policy team do not wish ill on Washington in the way that Nicolás Maduro or Vladimir Putin do, and in fact they see the United States as a critical partner on issues like climate change, energy and infrastructure investment. But they also believe the U.S.-led global order of the last 30 years has on balance not been good for Brazil or, indeed, the planet as a whole. They are convinced the world is headed toward a new, more equitable “multipolar” era in which, instead of one country at the head of the table, there will be, say, eight countries seated at a round table—and Brazil will be one of them, along with China, India and others from the ascendant Global South. Meanwhile, Lula has lost some of the inhibitions and brakes that held him back a bit during his 2003-10 presidency, and he is actively out there trying to usher the world along to this promising new phase—with an evident enthusiasm and militancy that bothers many in the West, and understandably so.

“A new geopolitics”

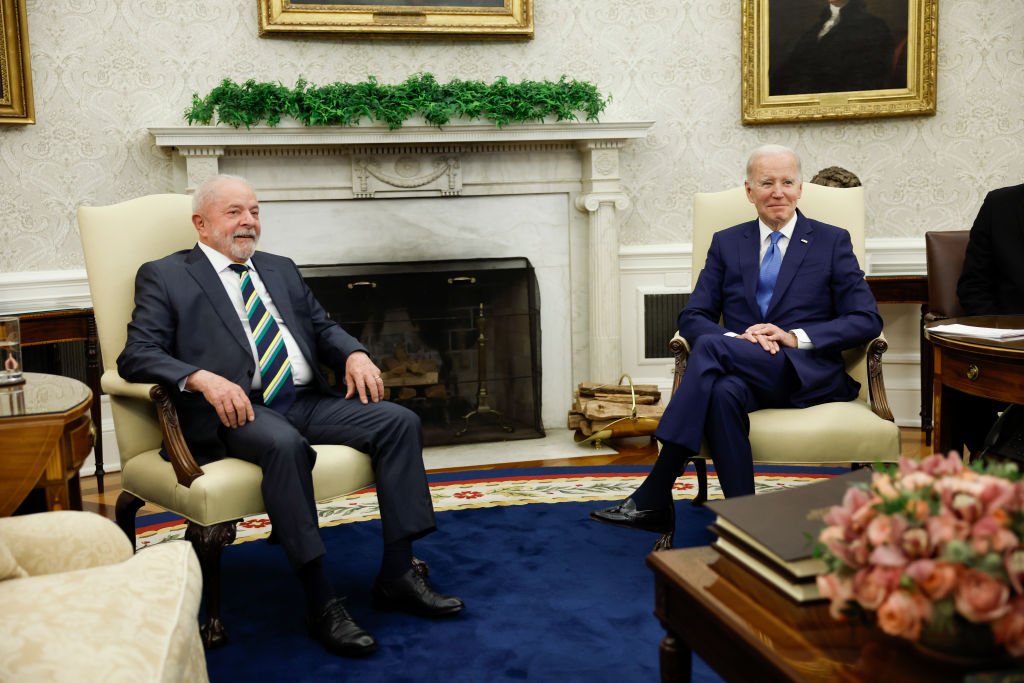

In private and in public, Lula’s allies vigorously reject the idea that he is anti-American — highlighting that he visited Washington within six weeks of taking office, and had a, by all accounts, friendly meeting with Biden. If the delegation Lula took to China two months later was far bigger and more ambitious, as many have pointed out, well, that’s realpolitik: China was offering Brazil much more in terms of investment and support, and now buys three times as many Brazilian exports as the United States. Lula was never going to continue the nearly automatic U.S. alignment that characterized much (though not all) of Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency. But he has a long record of pragmatic and often friendly engagement, including an apparently genuine personal bond with George W. Bush during his first presidency. When I met Lula’s top foreign policy adviser Celso Amorim in São Paulo last year for an otherwise off-record conversation, Amorim paused and emphatically told me: “This you can publish: It is in the interest of Brazil to have a positive relationship with the United States. No doubt.”

The idea that the world would benefit from a more multipolar order, and that Brazil should “actively and assertively” push in that direction, has been a mainstream tenet of its foreign policy for many years (thanks in part to Amorim, who was foreign minister the first time in the early 1990s). Brazil’s long, fruitless pursuit of a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, for example, is seen across the political spectrum as a sign that greater influence will have to be pried from the United States and Western Europe rather than politely requested. In that vein, Lula’s lobbying for peace in Ukraine can be understood not as instinctively anti-Western, but expressive of the doctrine that the world’s sixth-most populous nation should elbow its way if necessary into major issues of the day, as it did (or tried to do) during Lula’s first presidency on subjects like Iran’s nuclear ambitions, Mideast peace and Doha trade talks.

The problem, from the Western point of view, is that Lula and Amorim seem to think it’s not enough for Brazil to simply build itself up on the world stage. Rather, they seem to believe that, for the Global South to rise, Brazil should work to actively tear down, or at least weaken, the pillars of the U.S.-led order of recent decades.

The clearest evidence of this is probably not Lula’s stance on Ukraine or Venezuela, which have received the most attention, but his tireless advocacy for countries to abandon the U.S. dollar. “Every night I ask myself why all countries are obligated to do their trade tied to the dollar,” Lula said to applause during his trip to China. “Who was it who decided ‘I want the dollar’ after the gold standard ended?” He expressed similar sentiments when he hosted Venezuela’s dictator in May, and touted the idea of a common BRICS currency. It is worth noting that Brazil does not have a dollar scarcity problem; rather, it has vast reserves, meaning Lula’s advocacy can only be understood as part of a larger geopolitical project. Meanwhile, Lula focused his recent summit of South American leaders on a proposal to reestablish UNASUR, which was founded in the 2000s as a counterweight to the Washington-based Organization of American States (and later unraveled when it became too blindly leftist for most of its members). Brazil’s position on Ukraine is more complex—but Lula’s rhetoric, and cultivation of warm ties with Moscow more generally, has often seemed rooted in a desire to chip away at NATO, perhaps the ultimate symbol of the postwar order.

“Our interests with regard to China are not just commercial,” Lula said in Beijing. “We’re interested in building a new geopolitics so that we can change global governance, giving more representativity to the United Nations.”

Of course, these are valid strategic choices, and Brazil is hardly alone in these views. Lula and Amorim may in fact believe that Brazil’s future lies more with its BRICS partners than with a country where bombing Mexico has become a mainstream foreign policy idea in one of the two major parties. Similarly, it is easy to understand why the broader notion of a repressed Global South finally throwing off the shackles of domination by wealthy, formerly colonialist powers appeals to someone who sees the world primarily through the lens of class struggle, as Lula does. At age 77, and after his experience in prison, Lula may be past the point of biting his tongue and sense now is the time to move decisively on a variety of causes he has spent a lifetime pursuing. (Amorim, for the record, is 81.)

But there can be no doubt that the last six months have put Lula at odds with another cherished tenet of Brazilian foreign policy: The idea that Brazil can essentially be friends with everybody. The tone in Paris, Berlin, Brussels and Washington has been less one of anger, and more of surprise and disappointment among people who were deeply predisposed to embrace Lula, and Brazil more broadly, in the wake of the shambolic Bolsonaro years. Many have wondered, fairly, why Lula is so intent on bolstering the influence of dictatorships whose values don’t match his own 40-year record defending democracy in Brazil. Whether his actions have ultimately brought Brazil closer to its dream of greater global relevance, or more distant, is the biggest question of all, and will depend on what exactly happens next.

A rocky road ahead

There have been signs in recent weeks that Lula may be pivoting to a different approach. “I don’t want to get involved in the war of Ukraine and Russia,” he said on July 6. “My war is here, against hunger, poverty and unemployment.” This possible shift, if it holds, may be driven not by the Western backlash, but domestic opinion; recent polling suggests Lula’s foreign policy may be dragging on his overall approval rating in a country where, outside the left, most people have positive views of the United States and the West. But it is also unrealistic to expect a major change without a wholesale reshuffling of Lula’s foreign policy team—which almost no one in Brasilia expects to happen.

That means Washington must figure out how to cope. Some voices have urged confrontation, saying Washington should warn Brasilia that U.S. investment and other areas of cooperation will suffer without a change in tack. History shows that approach is almost certain to backfire, but it may gain more adherents as the 2024 election draws closer and Republicans seek to burnish their “anti-communist” credentials. (Lula is a capitalist, by the way, but that’s another column.) The Biden administration, wisely, has chosen a more mixed strategy; firmly pushing back against Brazil when necessary, but also trying to acknowledge its ambitions. Sources told me that during their February meeting, Biden told Lula he sees Brazil “not as a regional power, but a global power” —a comment that brought a vigorous nod from the Brazilian leader. Whether Washington can figure out a way to make that vision a reality, in a way that doesn’t undermine its own interests or the democratic order more broadly, remains unclear.