This article is part of AQ’s special report on sustainable development of the Amazon| Ler em português

The first thing people tend to notice about the pirarucu, a fish native to the Amazon, is that it’s absolutely, utterly horrifying. Adults in the wild can grow to a whopping 450 pounds (200 kg) and nine feet in length, which combined with its scowling face makes it look like a kind of Amazonian Loch Ness monster as it ploughs through the freshwater rivers of the world’s largest rainforest, surfacing every 10 minutes or so to gasp for oxygen (in another novelty, it is among the roughly 1% of fish species that breathe air).

Yet the pirarucu has an even more surprising characteristic, one well-known to both riverside communities and gourmets in faraway cities: It is delicious. With a tender, flaky white flesh that is flavorful without being overpowering, the pirarucu is often served in moquecas, the rich Brazilian stew of coconut milk, palm oil and cilantro, or just on its own. Figueira Rubaiyat, a famed steakhouse under a giant fig tree in São Paulo, long featured a simple grilled pirarucu alongside its better-known picanhas and bifes de chorizo. A few blocks away, Alex Atala’s D.O.M., which routinely makes global top 10 restaurant lists, has served pirarucu with tapioca or açai, the purple berry that also hails from the Amazon.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its taste and inconspicuous size, the pirarucu was nearly fished to extinction by the 1990s. A government attempt to ban all fishing failed to replenish its numbers. The turnaround didn’t begin until 1999, when the Mamirauá Sustainable Development Institute, a body funded by Brazil’s Science Ministry, launched an innovative plan in an Amazon reserve that allowed local communities to fish for pirarucu, but within set quotas and only during the dry season. It also incentivized them to better protect the rivers and surrounding forest while guarding their territory from poachers and loggers. This created a virtuous circle that allowed the pirarucu population in the Mamirauá project area to soar from an estimated 2,500 in the 1990s to 160,000 today, all while supporting a small fishing industry.

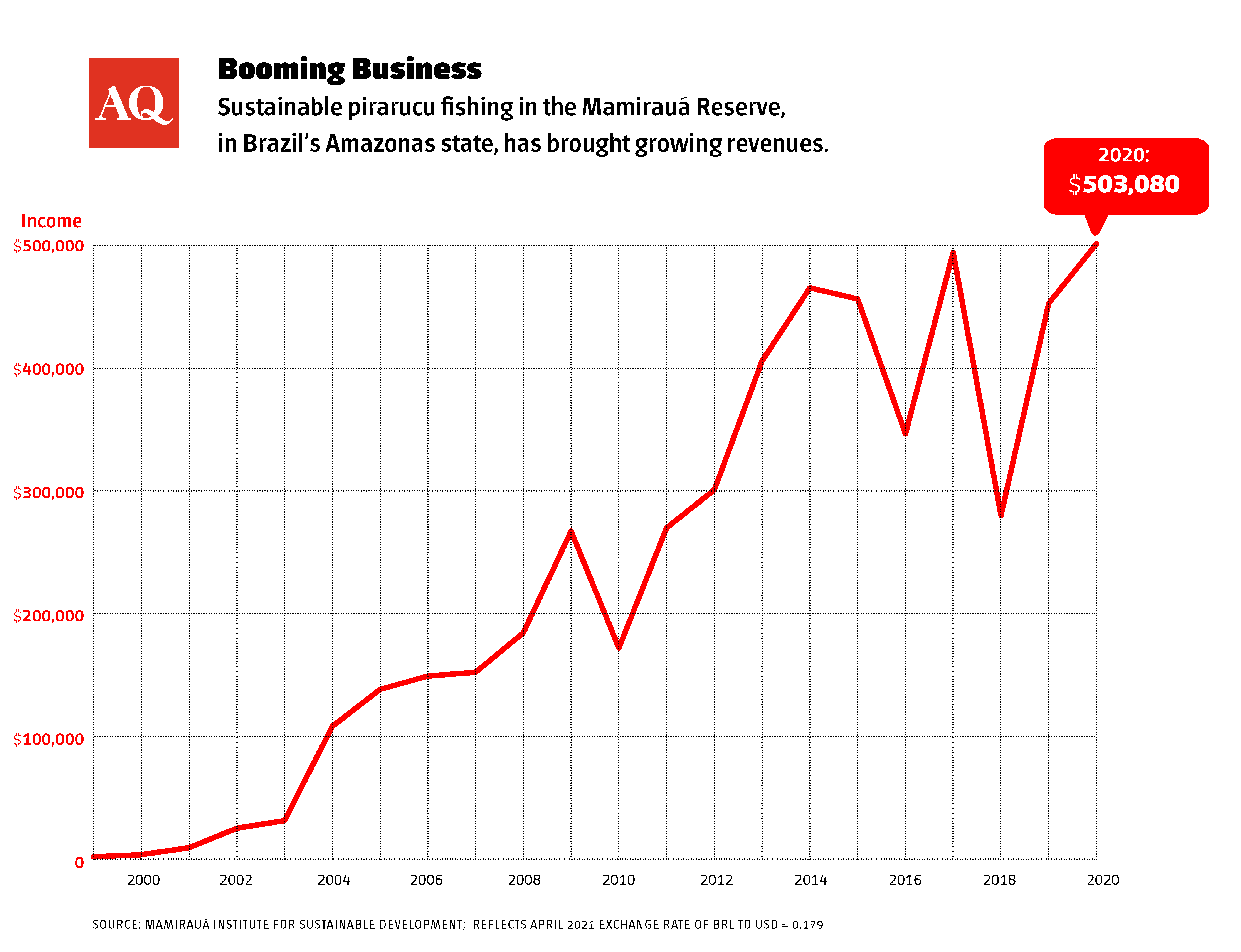

The prevailing sentiment in the Mamirauá reserve today is of under-exploited potential — that the industry could be worth more than the 2.7 million reais, or roughly $500,000, it currently generates per year for area fishermen. Producers elsewhere agree the pirarucu has room to grow. Foreign demand for it “exceeds all of Brazilian production, definitely,” Celso Gardon Machado, a fish farmer in Bahia state, told AQ, citing interest from the United States, China, Europe and Saudi Arabia. “I have received proposals where I had to ask for clarification because I thought a comma was in the wrong place.” Wild-caught pirarucu is especially sought after. But fishing collectives throughout the Amazon face numerous bottlenecks, from the region’s notoriously unreliable river-based transportation system to a lack of proper refrigeration equipment and continued high spending on security to chase away illegal miners, loggers and others who would destroy the fish’s habitat. A 112-page market study on the pirarucu published in 2016 by SEBRAE, a Brazilian small business agency, proclaimed the fish was “attracting the attention of numerous international investors who see high potential.” But five years later, that is still mostly a dream.

This blend of promise and frustration makes the pirarucu a symbol of today’s sustainable development efforts in the Amazon. The concept is clear enough: The natural wealth of the world’s largest rainforest could represent an economic bonanza for the Amazon basin’s 35 million citizens, potentially generating millions of green jobs inside and outside the region, if it is exploited in a sustainable and intelligent way. In an era when global consumers are willing to pay a premium for green products, and environmental and sustainability goals (ESG) are en vogue among multinational corporations and investment funds, this could have been the Amazon’s ideal moment for takeoff.

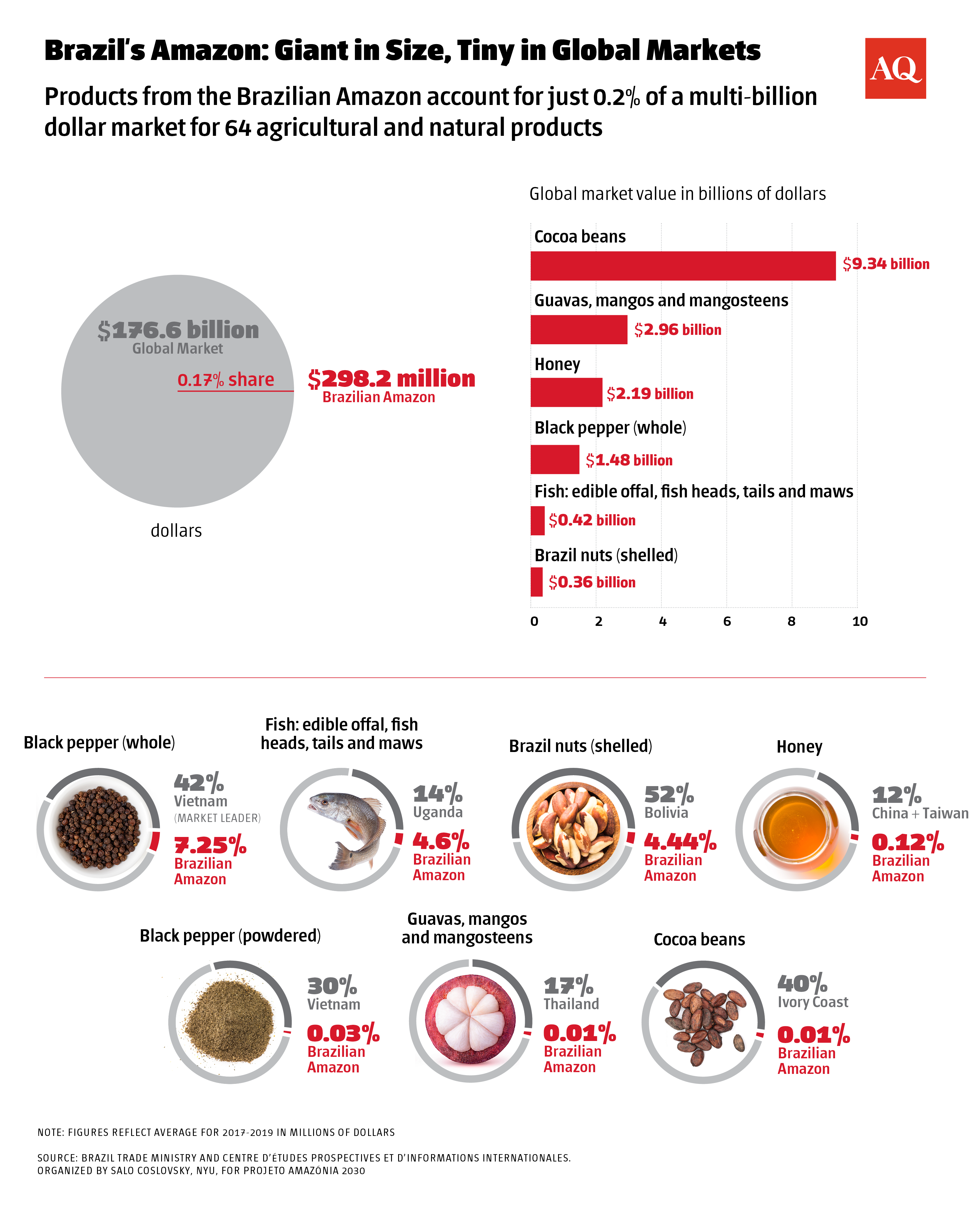

Some industries, such as cocoa, açai fruit and plant-based treatments for diseases like glaucoma, are indeed enjoying success. But most are still in an embryonic stage. Projeto Amazonia 2030, an initiative whose aim is to develop a blueprint for sustainable development, compiled a basket of 64 agricultural and natural products worth $177 billion on the global market — and found the Brazilian Amazon accounted for just a 0.17% share. Other countries with Amazon territory, including Bolivia, Peru and Colombia, face similar challenges. The barriers include logistics, a lack of capital, insufficient coordination among producers – and, almost always, politics. In Brazil, which accounts for about two-thirds of the Amazon’s overall territory, President Jair Bolsonaro’s insistence upon deforestation as an economic growth strategy has put Brazil on the verge of pariah status with the very global consumers whom sustainable producers need to win over. And while Bolsonaro’s government, particularly Environmental Minister Ricardo Salles, has tried to embrace at least the idea of sustainable development in recent climate talks with the Biden administration and others, this has in practice fed fears the whole concept is just a smokescreen, meant to distract public opinion while illegal loggers, gold miners and land-grabbers continue to set the forest alight.

Brazil’s private sector, including some agribusiness leaders, have energetically promoted sustainable development efforts over the past year – partly because they see its economic potential, and partly because they fear boycotts of their own products by U.S. and European consumers. But for sustainable development in the Amazon to be more than a feel-good story, or a nice side project for green investors and NGOs, there are numerous challenges it must still overcome.

Conserving the forest is key

The environmental and moral case behind sustainable growth efforts is compelling. The Amazon has been a global treasure for more than 30 million years, demonstrating incredible resilience through ice ages and other oscillations in the climate. The human presence there is recent by comparison, going back some 15,000 years. Deforestation has only been a major issue for the past half-century, since Brazil’s 1964-85 military dictatorship constructed highways and other infrastructure to stimulate development in the region. The regime did this not just for economic reasons, but also to prevent the region’s occupation by foreigners, reflecting a deep-seated fear of outside interference in the Amazon that has been at the heart of Brazilian military doctrine for more than a century. Integrar para não entregar, or “Integrate the Amazon so as not to give it away” in free translation, was a guiding slogan of the era.

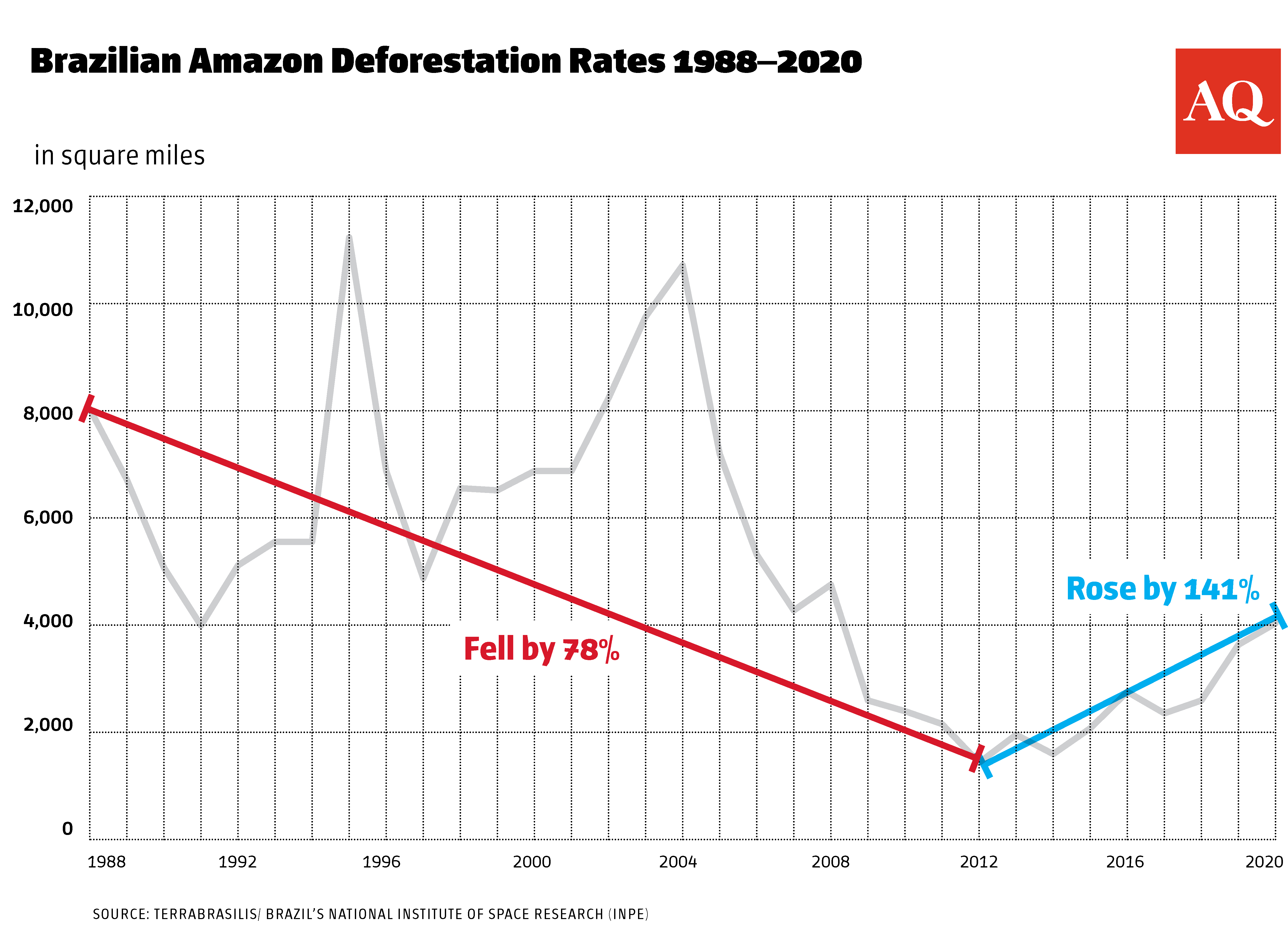

The disastrous effects on the environment are now well-known, with the Brazilian Amazon having lost about a fifth of its original area to fires and bulldozers since the 1960s. This has released massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and also threatened the integrity of the forest itself, which many scientists say is nearing a tipping point that could cause it to transform into dry savanna unless deforestation is halted in the next few years. Without a standing Amazon, the world will never meet the goals of the Paris accord; the damage to weather patterns (including the rains that sustain agriculture and hydroelectric grids throughout South America) and biodiversity is already being felt, and may turn catastrophic.

But the supposed tradeoff for all this destruction — economic growth — also failed to materialize. Today, the Amazon region accounts for just 8% of Brazil’s economy, exactly the same ratio as in 1980. Meanwhile, unemployment among young adults in the Amazon is 13 percentage points higher than Brazil’s national average, and especially affects the Black and Brown communities that make up 80% of the region’s population. Bolsonaro, a retired Army captain who still clings to many of the former dictatorship’s old philosophies, has argued that further deforestation is necessary to reduce poverty — “so that Indians can have a dentist, a TV, the Internet,” in his words. But that is clearly at odds with the experience of the last 50 years, in which the fruits of deforestation have accumulated only to a select few.

At the same time, forbidding all development in the Amazon hasn’t worked, either. The causes of deforestation are complex, with criminal gangs, legislation and political alliances in Brasilia, and global commodities prices all playing a role. But efforts to create green jobs, and give local communities (as well as faraway politicians) a greater stake in keeping the forest intact, have helped inhibit deforestation in areas beyond the Mamirauá project. It’s also true that, for productive purposes, Brazil has already cleared all the land it would ever need. Of the 80 million hectares that have been deforested since the 1960s, roughly 60% is used for cattle ranching with low productivity, while most of the rest (30%) is degraded or abandoned. Only the remaining 10% or so has been used with relatively high agriculture productivity. By using existing land better, there is plenty of room for growth; new techniques have been proven to increase cattle yields by more than 500%, to cite just one example.

Coping with a tough business climate

However, the pure economics of many sustainable industries remain challenging, without a doubt. Many Amazon products will probably always require customers to pay a higher price, given the expenses imposed by difficult logistics and sheer distance. Ana Claudia Torres of the Mamirauá Institute, which helped create the pirarucu rescue program in the 1990s, says the fish has clear appeal as a “premium product … a wild animal that comes with all the appeal of conservation and in the name of the Amazon.” Alexandra Bentes, a fish farming production researcher at Embrapa, Brazil’s prized agricultural research body, says consumer tests have shown “great acceptance” for the pirarucu in foreign markets. Others see potential for pirarucu skin, collagen from its scales and even digestive enzymes and soaps extracted from its entrails that could exceed demand for the filets themselves. But this all remains mostly a dream — in 2020, Brazil exported a measly four tons of pirarucu, about .07% of its total fish exports that year.

Entrepreneurs and local leaders point to several steps that could help make pirarucu and other Amazon products more competitive and scalable. Further research and access to capital will help maintain quality standards as producers try to meet demand while nurturing a fish that can grow by 15-20 pounds in a single year. “When you go to market with that kind of scale and volume, you have to have total control over the supply chain,” said Carlindo Maranhão, a fish farmer based in Rondonia state. In fishing and other industries, more skills training programs for workers would help create an environment in which products aren’t immediately exported to São Paulo or other faraway cities, as tends to happen today. More value-added production could take place in the Amazon itself, particularly in cities, where two-thirds of the region’s population resides. Another idea would be to connect early-stage Amazon entrepreneurs with peers in Silicon Valley and elsewhere in the world, so they can gain visibility and learn more about what it takes to compete on the global stage.

But the most urgent step is clear: For Brazil to begin to rehabilitate its image among global consumers, much less become a “green superpower,” it must first do a better job conserving the Amazon itself. Deforestation has to fall to zero, and soon, or the virtuous circle that helped save the pirarucu will never realize its potential – in this and other industries. Adevaldo Dias of the Carauari Rural Producers Association, which has helped organize Amazon-centric food fairs and “audition” the pirarucu for high-end restaurants throughout Brazil, says the model clearly works under the right conditions. “If the communities are given just and decent compensation for the sustainably managed pirarucu that they are bringing to market, the greater their motivation will be to protect the area,” he said. “And people will understand they are contributing to a better world.”

(additional reporting by Edmund Ruge)