It was one of the last major actions by Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso before he called snap elections earlier this year: signing a decree allowing civilians to own and carry guns legally.

Lasso justified the move as empowering citizens to defend themselves against a terrifying surge in violence. Ecuador’s murder rate has quintupled since 2016. But his response wasn’t unique: Lasso’s decree represented another victory for a growing movement on the Latin American right, which looks to the U.S.’s looser gun laws as a model for arming civilians to defend themselves against criminals with illegal weapons.

Under former President Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil led the way in loosening restrictions around owning and carrying guns—fueling a massive surge in private gun ownership. Despite new restrictions under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the number of registered guns in private hands has ballooned from 1.3 million in 2018 to nearly 3 million today, according to Brazil’s Instituto Sou da Paz, an anti-violence NGO. Argentina might be next: One candidate in the country’s hard-fought runoff presidential election, libertarian Javier Milei, has announced his intention to loosen gun restrictions.

The U.S. National Rifle Association, an arms industry lobbying group, has been seeking to promote gun rights across the Western Hemisphere for decades. But recently, coordination between conservatives in the U.S. and Latin America has taken on new prominence. Former Fox News host Tucker Carlson’s recent interview of Argentina’s Milei showcased an intensified exchange—and so have Latin American offshoots of U.S. Conservative Political Action Conference conclaves. There, a homegrown pro-gun movement is also on public view: At recent Brazilian installments of CPAC, Marcos Pollon, leader of a group called Proarmas (“pro-guns”), has been a repeated featured speaker.

As homicide rates soar in many countries, in a region already stricken by the world’s highest murder rates, calls to relax gun regulations may spread further.

Armed civilians in Latin America

Private gun ownership isn’t new in Latin America. Many countries allow for private citizens, including security guards, to purchase firearms legally. But there are often strict regulations around carrying them—and a battery of tests, including psychological examinations, are required before a permit is issued.

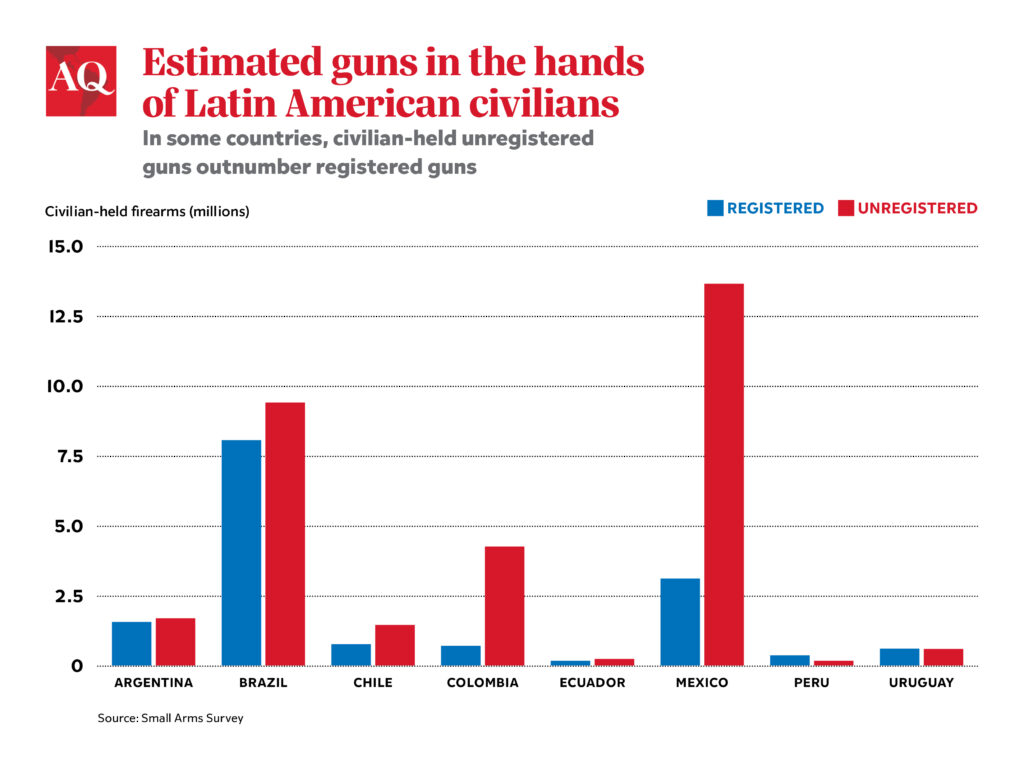

Meanwhile, criminals have long obtained guns on the black market—and illegal guns outnumber legal ones in much of the region, according to 2018 data from the Small Arms Survey. In Argentina, the difference is small: around 1.5 million registered guns versus 1.7 million unregistered ones. But in Mexico, of nearly 17 million guns in civilian hands, only 3 million are estimated to be legally registered.

What is new are demands by politicians—and by sectors of the population that support them—in favor of looser gun regulations. These demands reflect the idea, long entrenched in the U.S. but relatively unpopular in Latin America, of the armed “good citizen” defending society against crime.

Brazil is the country where, so far, efforts to make it easier for citizens to buy guns have had the greatest effect. While in office, Bolsonaro used presidential decrees—more than 20 of them—to remove restrictions on buying guns and increase the number of guns available to the general population and specialized hobbyists. Moves allowing hobbyists to carry firearms on the way to a gun club or competition represented “in practice … a license to carry guns,” said Bruno Langeani, a researcher at Sou da Paz.

The influx of legal guns soon flooded the black market with more powerful weapons than ever seen before. In São Paulo, the prevalence in the illegal market of semi-automatic pistols has tripled since 2018, according to Sou da Paz, the rise continuing under Lula. Experts expect the surge in gun ownership under Bolsonaro to have repercussions on the illegal market for the next two or three decades.

Many of Bolsonaro’s looser regulations, which polling had suggested were unpopular, were reversed by Lula, who has reduced the number of firearms available to private citizens to two and required owners to re-register their guns. In Brazil, like in most of Latin America, regulations on civilian-owned guns are still significantly stricter than in the U.S.

But these and other changes haven’t reversed a massive increase in firepower in civilian hands in Brazil. A proposed buyback campaign hasn’t taken shape. “[Lula] imposed restrictions for the future, but he’s not making radical changes for the gun owners that bought weapons during Bolsonaro’s government,” said Langeani.

The limits of Lula’s reversal of Bolsonaro-era gun policy seem to reflect not just the logistical difficulty of getting guns out of civilian hands once they have been acquired, nor only the continued strength of Brazil’s gun lobby, but also deepening divisions in public opinion on the subject.

In July, asked if owning a legal firearm for self-defense should be a legal right, 50% of Brazilians polled agreed, and 48% disagreed. Not lost on gun advocates is the fact that homicide in Brazil declined during Bolsonaro’s government, though some experts see factors other than looser gun policy behind the decline.

Armed citizens and the state

The Latin American right wasn’t always in favor of getting more guns in the hands of civilians. In Argentina, for example, “The traditional right wing never wanted an armed society,” said Maria Esperanza Casullo, a political scientist at CONICET and the University of Río Negro. “They wanted a society with no guns and a police [force] with lots of guns.”

Indeed, the drive to expand legal gun ownership often comes hand in hand with ideas about civil resistance to government. “An armed people will never be enslaved,” Jair Bolsonaro said last year. Some of the politicians who have championed relaxing gun laws are anti-statist libertarians (Milei), or have libertarian leanings (Lasso).

“There’s a great effort by right-wing governments to weaken the state and place all responsibility with civil society or private actors,” said Gualdemar Jiménez, an arms researcher in Ecuador. There’s a class dimension here, too, Jiménez said: “Let’s be realistic: Not everyone has the money to buy firearms.”

Others say these anti-state tendencies coexist with the desire to give more power to state security forces. Bolsonaro, for example, while in office, both supported private gun ownership and advocated a tougher approach on criminals by law enforcement.

Not all right-wing leaders in the region promote looser gun laws. Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele might pose for photos with high-powered firearms, but he hasn’t overseen a notable loosening of gun ownership restrictions—preferring to combat crime with a sweeping state crackdown on gangs.

In countries that have seen relaxations of gun laws, experts are especially worried about attempts to relax controls on carrying guns in public, rather than just owning them—something that has been firmly prohibited in most countries until recently.

“That’s the most dangerous part of all,” said Carina Solmirano, a security expert at Control Arms, a nonprofit. “It basically means going back to Hobbes’ state of nature. … Everyone is armed and carrying their weapons on the street, resolving issues in their own hands.”