BRASÍLIA — Over the last decade, Brazil’s Congress has dramatically increased its power, reducing the scope of the “hyper-presidentialism” to which Brazil has long been accustomed. It’s a development that looks set to present a new and considerable check on the power of the next president—whether that will be former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, or incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro.

To understand the rise of Congress, look to Brazil’s recent history. When Dilma Rousseff (Workers’ Party) was president (2011-2016), one of the main criticisms she received from her coalition, including her party, stemmed from her centralizing figure and little opening to dialogue with the legislature. This led to several initiatives from Congress seeking to increase its own power, consequently reducing the influence of the executive branch.

For example, the Brazilian Congress has always officially had the last word on creating new laws, but in practice, this has changed a lot in recent years. Since the return to democracy, the president has had the power to veto a bill of law approved in Congress. Congress always had the power to accept this veto—or not.

Historically, Congress would accept the decision of the president. But in 2013, this began to change. Former Speaker of the House Henrique Eduardo Alves, a member of Rousseff’s coalition, pressured by allies unsatisfied by her lack of dialogue, proposed and approved a new strategy for vetoes. Congress now had a short period to analyze and vote on presidential vetoes. If these vetoes were not voted on, other scheduled votes were blocked from proceeding.

This change was revolutionary and had consequences. By simply analyzing vetoes, Congress understood its power to negotiate demands with the executive branch. Rousseff had more vetoes overruled than her predecessors, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, and Lula da Silva. Bolsonaro, meanwhile, has more vetoes overruled than Rousseff, Cardoso and Lula put together.

Around the same period, another significant change also reduced hyper-presidentialism in Brazil. Amendments to the budget proposed by lawmakers became mandatory. Before, acceptance of these amendments depended on the executive branch, which would favor loyal members of its allied base, providing stimulus to pork-barrel spending. Today, each member of Congress gets around 15 million reais in amendments to the yearly budget. This has dramatically reduced the submissive behavior of the allied base toward the president.

During Bolsonaro’s administration, Congress approved only 34% of his proposed measures, a record compared to past presidencies. Although Bolsonaro was reluctant to negotiate directly with Congress, this number is also a consequence of the legislature’s independence. If we analyze only provisional measures, the president’s most powerful legislative tool, only 49% of them were approved, against 90% for Lula (2003-2010) and 87% for Cardoso (1995-2002) and Itamar Franco (1992-1994).

Other regulatory changes have also been made that contribute to increasing checks and balances in the country. Recently, Congress approved the formal and legal autonomy of the Brazilian Central Bank. The current governor of the Brazilian Central Bank, Roberto Campos Neto, has a mandate until December 2024, regardless of who wins the election on October 30. Few other emerging markets can say the same.

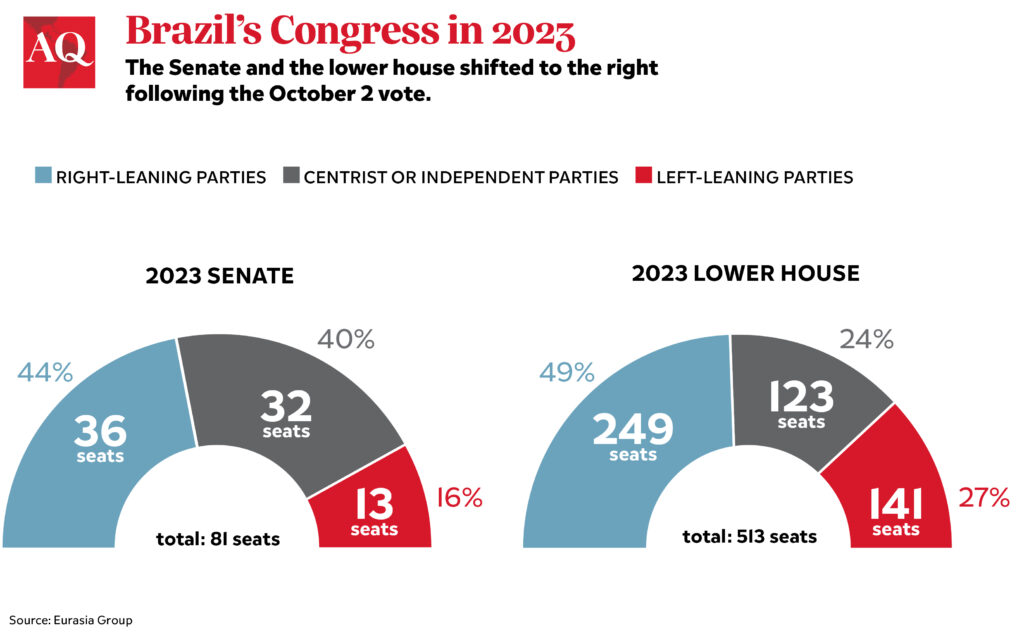

Considering the Congress elected on October 2, neither Bolsonaro nor Lula has an ideological base to create a simple majority, let alone the supermajority required to make changes to the Constitution.

The polarized national election has enhanced the regional variable on party dynamics. Several centrist parties supported Lula in one state but Bolsonaro in another. This led to lawmakers in the same political party reaching Congress with very different messages. Whoever wins will need to engage in retail politics, sometimes negotiating votes on the individual level. Negotiating deals with party leaders is no longer enough and the power of the whip is not as strong as it once was.

Bolsonaro’s victory would mean a clearer path for items such as administrative reform, privatization of the postal service, new sectorial benchmarks and a more market-friendly change to the spending cap. Lula’s victory would mean a more narrow path towards some campaign promises, including total repeal of the spending cap, alterations to the 2017 labor reform and increased spending for infrastructure investments.

From 2018 to 2022, Bolsonaro enjoyed support in Congress for his economic proposals but failed to advance his conservative agenda. From 2023 onwards, the scenario remains similar: a president elected without a completely compatible Congress. Bolsonaro has a more straightforward mission but will need support from parties outside his inner circle. Lula, meanwhile, has a more arduous road to a majority, and dilution of his proposals will be necessary to get there.

The Brazilian Congress has cooperation with government in its DNA, and it will almost always find a way to create a base susceptible of working with the incumbent president. And being close to the president still has benefits. But the submissive mentality has changed. We now see increased independence and a scenario where governability is no longer an imperial right, but rather the subject of tough negotiations, in which key players, even allies, are usually outside the president’s ideological realm.

In a campaign, candidates own their proposals. In a political system such as Brazil’s, the president is a shareholder of the government, not its owner. It is fair to say that political power in Brazil has never been so diluted and shared as today.

—

Aragão is partner at Arko Advice.