A year ago, the Latin America and Caribbean region was considered a global symbol of pandemic failure. With 8% of the world’s population, it was reporting nearly a third of worldwide COVID-19 deaths. Hospitals were overwhelmed, bodies were piling up, and those who could afford it flew to cities like Miami to get vaccinated.

Just 12 months later, almost 70% of the region’s population is fully vaccinated, surpassing many industrialized countries. The average number of deaths per capita is now lower than in Europe and the U.S. and by the first half of May the region was reporting 9.6% of global deaths.

That percentage has risen recently alongside a new winter wave in South America, but the region’s achievement still stands out. And the story behind it holds important lessons for the future.

The region clearly benefitted from the unprecedented push by industrialized countries and pharmaceutical firms to develop vaccines. At first, “vaccine nationalism” favored the richest countries, but by mid-2021, Latin American governments had jumped into this dynamic new market and aggressively negotiated large vaccine purchases from multiple manufacturers.

Once it was apparent that economic recovery would be impossible without large-scale vaccinations, the region’s finance ministries did their part by releasing the funds necessary to close deals. Governments also quickly removed regulatory and legal hurdles that could have slowed vaccine deployment.

Argentina, Brazil and Mexico leveraged expertise in clinical trials and drug manufacturing to broker deals with pharmaceutical firms that needed to test and prove the efficacy of new vaccines. And in a reflection of the region’s multi-polar geopolitics, most countries simultaneously sourced jabs from North America, Europe, Russia and Asia, improving their chances of securing supplies.

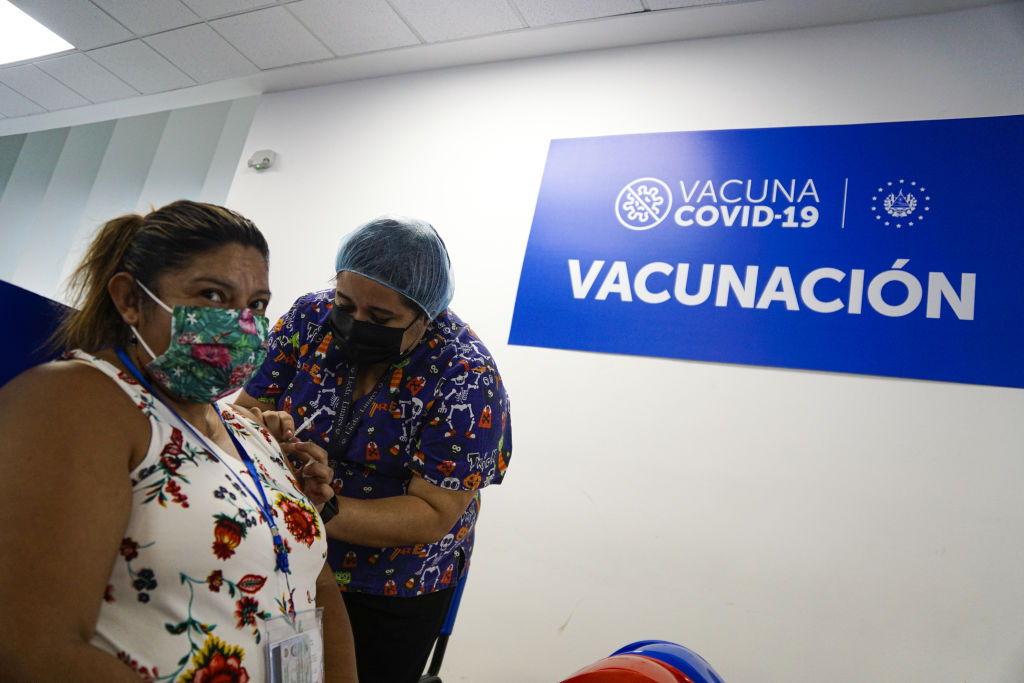

As vaccines began to arrive, governments chose unconventional approaches to overcome the daunting challenge of delivering hundreds of millions of two-dose regimens. Some awarded contracts to private logistics firms that had robust national distribution networks, while others tapped the armed forces to help administer shots. Many rolled out sophisticated communications campaigns to orchestrate coordinated efforts over vast territories.

But perhaps the critical factor in the success of these efforts was public trust. Despite a torrent of misinformation on social media, highly polarized politics and surveys that indicate nine out of 10 people in the region distrust each other, Latin Americans showed relatively low levels of vaccine hesitancy.

This is largely because in most of the region’s countries, public health authorities have run effective vaccination campaigns every year, for decades. This legacy of credibility paid off during the pandemic, as churches, schools, private companies and civil society organizations joined forces to assist public authorities with the vaccination drive. As a result, all but a handful of countries reached high vaccination rates in record time.

Of course, Latin American and the Caribbean remain vulnerable to COVID-19 variants, and vaccine coverage remains starkly unequal, ranging from 92% in Chile to under 2% in Haiti.

Although the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) helped the region obtain vaccines through COVAX, the global vaccine purchasing and sharing program, the region missed an opportunity to form a unified regional purchasing block representing some 650 million people. In the future, the region should increase its bargaining power by adapting the European Union’s approach to negotiating advance-purchase agreements.

Developing a strong, well-governed regional fund for joint procurement of vaccines and other health technologies, strengthening existing mechanisms or structuring new ones would also send a positive signal to the private sector, which would have greater incentives to invest in local production capacity. Countries should also work even closer with the IDB to strengthen regional supply chains. This could generate a virtuous cycle that reduces Latin America’s dependence on imports.

On this front, the region got a boost on June 22, when European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and President Pedro Sánchez of Spain announced the EU would work with the IDB to help Latin America and the Caribbean produce world-class vaccines at home.

Given the multitude of legal hurdles that the region’s countries had to overcome to purchase and deploy coronavirus vaccines, governments should also finish the job of modernizing regulatory frameworks and improving their capacity to prevent, prepare for and respond to future public health emergencies.

Still, the success of COVID-19 immunization programs in Latin America, a region far poorer than the U.S. or Europe, shows that local clinics with well-trained staff and access to the right technology can be the backbone of a resilient and innovative public health system.

Now, the region’s governments should capitalize on this experience and push to modernize the primary health care system. They should also step up collaboration with the IDB, which is working with several governments to accelerate the digital transformation of healthcare to improve access, quality and efficiency.

Latin America is as polarized as the U.S. and Europe. Its vaccination success shows that investing in key public policies can help overcome political divisions to improve lives. It also demonstrates that building trust in institutions can yield big results.

Research shows that improving trust can increase innovation and accelerate economic development. This is a lesson that should inform decision-making in every country.

If we seize this opportunity to build on Latin America’s vaccine success, this remarkable achievement could lay the groundwork for lasting gains, potentially even making the region a leader in equitable healthcare.

That would be a win not just for Latin America, but for the entire Western Hemisphere, improving the wellbeing and productivity of people throughout the Americas.

__

Claver-Carone is president of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB)