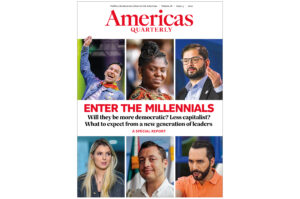

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on millennials in politics | Leer en español

Chile’s former President Ricardo Lagos (2000-06) is one of Latin America’s true statesmen. Now 84, he also began his political career quite young—in 1972, when Salvador Allende designated him ambassador to the Soviet Union. In this interview, he speaks to AQ editor-in-chief Brian Winter about why he’s bullish on today’s young generation of politicians, including his successor as president: 36-year-old Gabriel Boric.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Americas Quarterly: In Latin America, Chile is the most emblematic case of a new generation that has taken power. In your opinion, what makes them different from previous generations?

Ricardo Lagos: Well, I’d say it’s been a very successful group from a political point of view. I remember when many of them started, as a new generation in the student organizations in 2010 and 2011, when there were student protests in Chile. They were the leaders.

AQ: Would you have ever imagined at that time that, 10 years later, they would be running the government?

RL: Never! They seemed so young. Anyway. Some of them went directly from receiving money from their parents to study in the university to the stipend that legislators receive from parliament. That’s not a bad way to start a political career. And they were very successful at capturing people’s imaginations.

And you saw the latest, right? In which one of them even became president. There wasn’t even a debate on who was going to be the candidate, because several of the others (from the group of former student leaders), who could have been candidates, weren’t yet of the age the constitution requires to be president. (Ed. note: The age is 35.) Isn’t that amazing? One could say that Boric is ‘the oldest’ of the group, and that’s why he became president.

AQ: How do you think their values are different from past generations?

RL: Well, I’d say this stems from a country that has had fast economic growth. To cite just a few figures: In 20 years, Chile saw its average income double, to $22,000 per person. However, it maintained the same fiscal income, at about 20% of GDP. A richer Chilean society implied that society was demanding more goods and services from the state.

Today in Chilean universities, for every 10 young people, seven are the first generation in their family who gets to the university. Well, we’re also very proud of that, but it must be paid for. How can you have such fast economic growth, but the fiscal income stays the same? So, there’s a dissatisfaction because I’m earning more than before, but I can’t get to the end of the month, when before I could. So you have this situation where we have more money, we have more resources, but we’re also more unhappy.

When you have the social explosion in Chile, the famous October of 2019, when we had the origins of this need to produce a new constitution, that’s when it became indispensable to understand this task we had before us.

AQ: Throughout Latin America we see a generation of young people with a lot of focus on inequality, on public services, as you just mentioned, and on climate change, among other areas. What do you think today’s young people are missing, though? Are there any lessons they haven’t learned yet, or have forgotten?

RL: I think they’re lacking a certain knowledge of the apparatus of the state, and how it works, what its problems are. It’s not enough to think “I want to improve and have better taxes and to have …” No! How do you do it? What are the tools? And that requires experience, that requires experience. It’s not easy.

AQ: You began very young in politics as well, more than 50 years ago. If you were young again, would you go into politics?

RL: It was a different era. I’m from the era of the Industrial Revolution. The world was clear and simple. There are a few who have the capital to buy the machine. There are the others who only have their labor to make the machine run. So the world is divided between those (two groups). You see? How clear it is, there’s left and right, you see where everybody is.

Now, instead, we’re going through a digital revolution. This is a Copernican change, a new world is emerging. … The power centers are less clear. When you talk about the United Nations, the Millennium Development Goals—these are things that come from the industrial world. We still have to reduce poverty, we have to improve the distribution of income, all of that. But there are new questions we’re only beginning to understand.

AQ: Does this new generation make you more skeptical, or more optimistic about the future?

RL: I’m optimistic about the world we’re headed toward. I have no doubt. When he got to the second round (of the 2021 election), I came out and immediately said: We have to support Boric, you know? I think this new generation is very positive. Will they have difficulties? Yes. But they’re going to move forward, I believe.