Ahead of an impeachment vote on December 7, now former Peruvian President Pedro Castillo dissolved Congress and stated that he would install a “government of exception” to rule by decree until a new Congress was established. Congress continued the vote regardless and impeached Castillo, elevating his vice president, Dina Boluarte, to the presidency.

Castillo had also announced a reorganization of the judiciary, enforced a curfew and ordered citizens to turn in their firearms.

AQ asked observers to share their reaction. We will update the page as developments arise.

Subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify, Google and Soundcloud

Luis Miguel Castilla, economist, former finance minister of Peru

This presidency finished the same way it was carried out for the last 16 months: with arbitrary measures. Just this morning, the opposition did not even have the 87 votes needed to impeach Castillo. They did not have Peru Libre’s support and Vladimir Cerrón even tweeted earlier today that they would not vote to impeach.

But then Castillo decided to close Congress and quickly turned the tide against himself. We were expecting an official announcement by the Armed Forces—which would be the only way Castillo could pull this off—but they were clear on their support for the constitution. In fact, all institutions in the country were fast to denounce Castillo’s unconstitutional move.

Now the new president, Dina Boluarte has a real challenge ahead of her. She needs to call a cabinet of unity. Boluarte will have Congress’ support initially, but she needs to build a coalition fast or she will be met with instability in just a few months.

My first reaction today was of shock, but again this government was so unstable and kept improvising everything, that this is a much welcome quick and swift resolution to the last 16 months of crisis.

Will Freeman, Ph.D. candidate in politics at Princeton University

The worst outcome in Peru has been avoided. Fortunately, Congress, the Armed Forces and Police, the judiciary, and Vice President Dina Boluarte quickly lined up to say Castillo’s attempt to install a “government of exception” would receive no support, and Castillo was placed in police custody. On one hand, the speed and unanimity with which Peru’s institutions said no to the coup attempt was encouraging. Conflict between branches of government may look more like a bar fight than healthy checks and balances, and frustration with government dysfunction may run deep. But when it comes to preserving Peru’s electoral democracy, some (minimal) red lines do hold. Virtually all the major players across the political spectrum and branches of government seem to agree that a break with the constitutional order and regular elections would be bad for the country—or, at the very least, for their own interests. Castillo’s bungled self-coup shows that no matter how frustrated Peruvians might be with runaway government dysfunction (and they are frustrated), no political force has been able to channel that discontent into support for an autocrat—yet.

But that may be more a problem of supply than demand. The LAPOP survey has shown year after year that support for executive coups in Peru is more widespread than in other Latin American democracies. Castillo’s autogolpe likely failed because of his terrible track record governing, which made him unpopular both with the people and with other branches of government. But what if a savvier president comes along and copies Castillo’s maneuver, only with popular support or allies in a few other key institutions? We shouldn’t be too confident that we would see a repeat of the unanimous and quick pushback we see today. There are figures waiting in the wings, like extremist-nationalist Antauro Humala, who want to dismantle Peru’s democracy—only they’re more serious about doing so than Castillo was. The saying goes that “history repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.” Let’s hope Peru doesn’t prove the logic works in reverse: Castillo’s autogolpe was a farce, but it could easily be followed by tragedy if Peru’s institutions can’t find consensus on addressing some of the country’s most pressing problems.

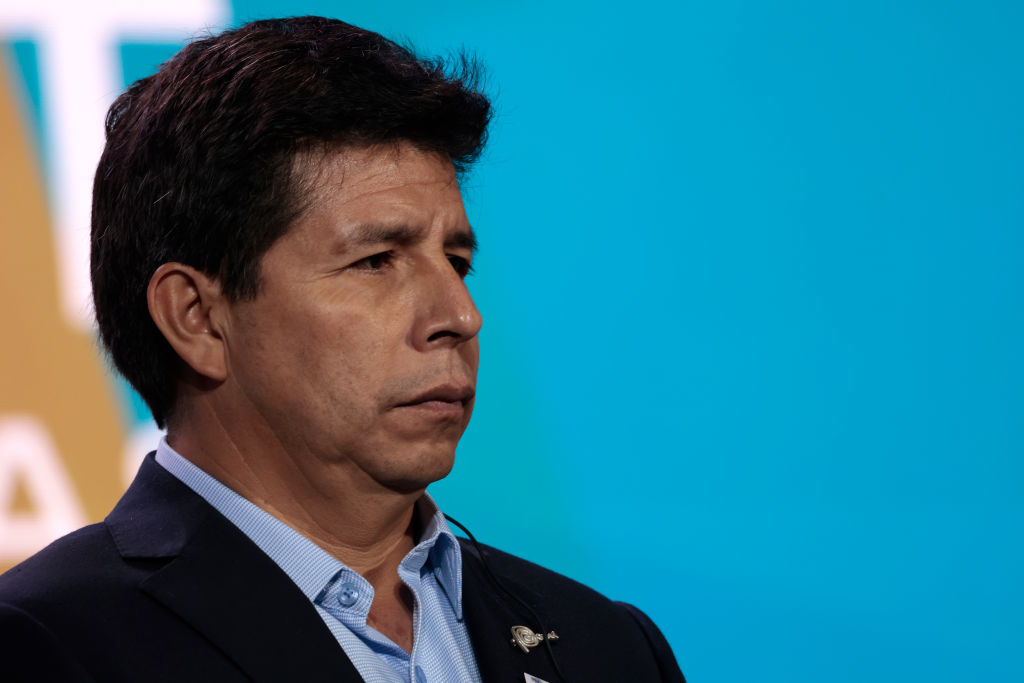

(Photo: Vachira Vachira/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Andrea Moncada, Peruvian political analyst

Castillo’s decision to dissolve Congress just as legislators today were getting ready to vote on his impeachment is a show of the president’s weakness and lack of political strategy. The move is unquestionably unconstitutional—the only lawful way to shut down the legislature in Peru is if the president gets two consecutive votes of no confidence, which has not happened. This will convince those parliamentarians who were on the fence about removing him from office to vote for his removal now, perhaps even those from his old party, Peru Libre, who had already been upset with the threat of dissolution a few weeks ago. His ministers and other high-ranking public officials are quitting en masse. It’s clear that Castillo thought this was his way to avoid getting impeached, but it was an impulsive, badly thought-out decision.

What it all comes down to now is whether Peru’s armed forces choose to support the president. That also looks unlikely to happen. The commander general of the armed forces resigned about an hour before Castillo’s address, in what is now a clear sign of disapproval. The president does not have a close relationship with the army, as was evident when he tried to influence promotions early on in his term. It looks like Peru will have a different president by the end of today, December 7.