A little over a year into Pedro Castillo’s administration, many Peruvians are wondering how their embattled president is still holding on to office. And now Castillo is facing the biggest challenge to his presidency to date. In the last two weeks, a congressional subcommittee voted to go ahead with two constitutional accusations against him—as Castillo responded by moving to set up the conditions that could allow him to dissolve Congress.

The first accusation is for treason, based on Castillo’s statements that he would hold a referendum to ask the population whether Peru should give neighboring Bolivia maritime access. The second, presented by the attorney general, alleges that the president is the head of a criminal organization that seeks to obtain bribes in exchange for governmental contracts. If these accusations are eventually approved by the legislature, they could potentially strip Castillo of his presidential immunity, allowing the prosecutor’s office to formally charge him, and Congress to remove him.

Many people, including myself, thought that such a weak president wouldn’t last very long in power. When he was elected in 2021, Castillo had no majority in Congress, no real allies among Peru’s political class, no governing experience—and the opposition was clearly out to get him. The specter of impeachment was present right from the beginning and there have already been two attempts to initiate proceedings. There have also been regular protests in Lima demanding his resignation. The latest developments suggest that Congress is determined to deliver the final blow one way or another.

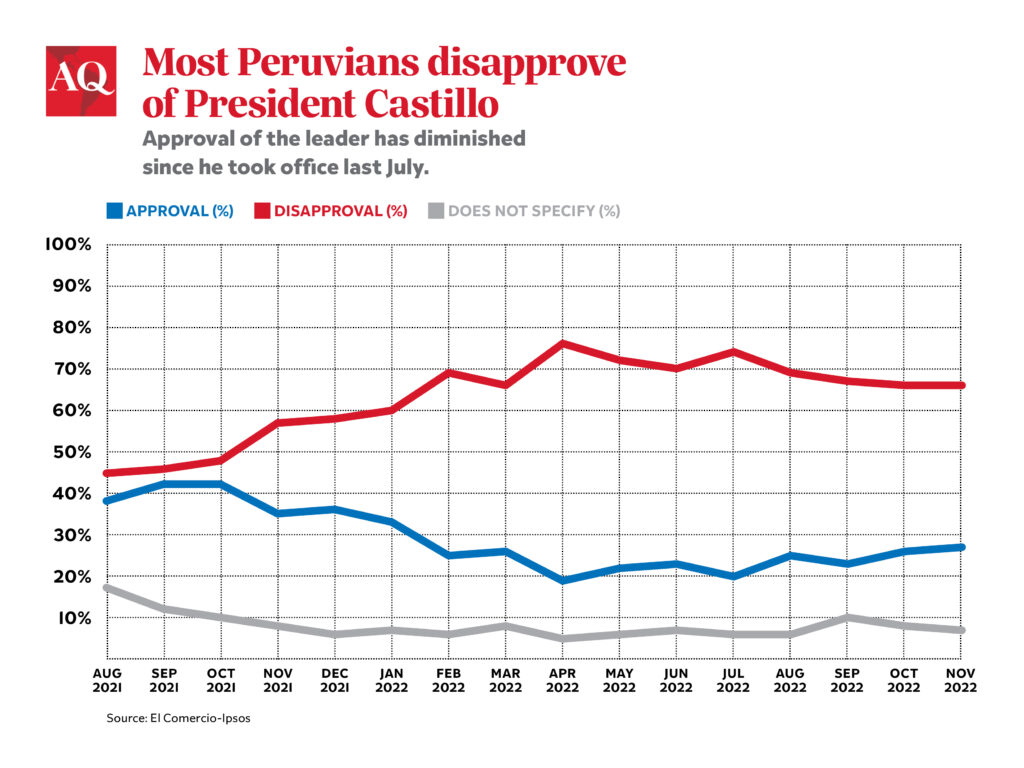

But despite his unpopularity—the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos registers an approval rating of just 28%, and El Comercio-Ipsos, just 27%—Castillo has two cards up his sleeve that could prove decisive for his survival. First, if there is anything close to an axiom of Peruvian politics, it’s that anti-corruption sentiment is intimately tied to anti-fujimorismo. Every single large-scale protest in Peru in the past five years has been a rejection of Keiko Fujimori, of her party, Fuerza Popular, or of individuals perceived to be allied to fujimorismo. When former Attorney General Pedro Chávarry tried on New Year’s Eve in 2018 to dismantle the special team in charge of investigating the Lava Jato cases, people came out into the streets because they saw him as an avatar of fujimorismo.

After the impeachment of former President Martín Vizcarra in 2020, week-long nationwide protests were likewise sparked by Peruvians’ belief that the individuals who removed him—mainly legislators from Acción Popular, a center-right party—were doing it to benefit both themselves and Fuerza Popular as well. Despite all the credible accusations of corruption against Castillo (who maintains his innocence), for many Peruvians they’ll never be as bad as anything Fujimori could do.

Second, no matter how much Peruvians distrust Castillo, they dislike Congress even more. Almost all parliamentarians are seen as fundamentally corrupt and self-serving, particularly so after Vizcarra’s impeachment. There may be small protests against the president, but it’s hard to imagine large swaths of the population getting behind any congressional action, even more so considering Acción Popular and Fuerza Popular are the two main opposition parties.

It’s possible that the president is aware of this. It might explain why the prime minister, Aníbal Torres, asked Congress last Thursday for a vote of confidence on a bill that would overturn a recently approved law limiting the use of referendums. The speculation is that Castillo’s aim is to dissolve the legislative, which he is permitted to do if Congress defies the executive on two consecutive votes of confidence. Torres has denied this, claiming that the bill curtails constitutional rights—even though a constitutional tribunal has already ruled in the bill’s favor earlier in the year. Given the country’s history with congressional dissolutions—Martín Vizcarra did so in 2019, and infamously, so did ex-President Alberto Fujimori in 1992, marking the beginning of his dictatorship—this is tantamount to the nuclear option. At the same time, it’s unlikely many Peruvians would care very much if Congress were shut down.

Castillo has also resorted to a peculiar strategy: petitioning the Organization of American States (OAS) to apply its Democratic Charter, alleging that both Congress and the attorney general’s actions present a danger to Peru’s democratic order. Officials from the OAS are now meeting in Lima with all the parties involved, but the most the organization could do is strip Peru of its right to vote in the OAS assembly—not exactly a solution to the country’s current crisis.

In any case, it’s not far-fetched to conclude that the executive is doing what it can to stop the congressional investigation against Castillo. But they’re on the back foot: Since Thursday, most parties have signaled that they will simply disregard the request, as votes of confidence only apply for bills considered state policy. If this happens, the government has said it will consider it as a vote of no confidence, triggering a crisis in Cabinet, but it’s hard to see how a ministerial reconfiguration would help Castillo at this time.

In short, the two powers find themselves at a standstill, and it’s increasingly difficult to predict how the clash will end. Castillo may choose all-out confrontation with the legislature, banking on its unpopularity—or he might hope the two constitutional accusations, which will take a few months to resolve, will come to nothing. For now, neither side has a clear advantage in Peru’s constitutional war of attrition.