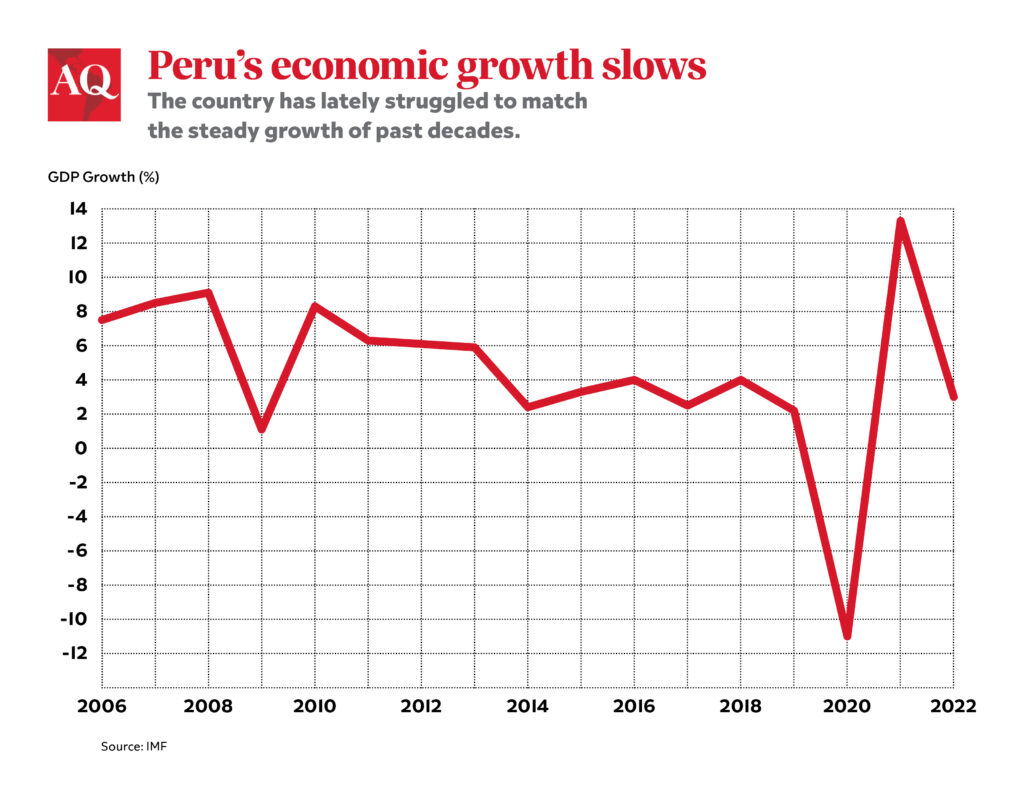

Peru’s economy was once dubbed a “miracle” by analysts who marveled at its stability despite years of political chaos. But now, it’s facing tough times.

Despite a strong rebound in 2021 after the COVID-19 pandemic, Fitch Ratings has revised down its projections for GDP growth in 2022 from 2.5% to 2.3%. Similarly, the IMF has adjusted its projection from 3.3% to 2.8% and has announced that Colombia’s growth rate looks set to overtake Peru this year. Analysts have pointed to adverse global financial conditions, including high inflation and less demand from China, Peru’s main trade partner and the biggest consumer of its mineral exports.

There is no doubt that Peru is not performing as it once did. But what’s new is that the country’s economy is finally being affected negatively by political crises. A recent Reuters article noted that Peru’s central bank had recorded the lowest level of investor confidence since the 2008 recession, due to the series of corruption scandals and constant cabinet changes of Pedro Castillo’s government. According to Fitch, “politics and the economy can no longer be treated separately.”

But how fair is it to say that the Castillo administration is fully to blame for Peru’s economic woes? While the country’s governability has always been shaky, Castillo has taken this to new levels. Currently, the president is facing six criminal investigations that implicate him directly in bribery and other corruption schemes and include his wife and sister-in-law as well as several other close associates. He has reshuffled his cabinet 59 times in a year, which means that there has been a new minister every week on average. Congress is also not helping matters; so far it has tried twice to impeach Castillo and will likely try again. The general chaos prompted over 200 business organizations to sign an open letter in July condemning all the corruption allegations against the president and demanding that Congress remove him if these continue to appear.

It’s not surprising that Castillo is facing opposition from business groups, due to the alarm his presumed leftist agenda caused since the beginning of his presidency. But Peru’s economic troubles go beyond investor confidence. It was only a matter of time until the country’s economy could no longer solely rely on its solid macroeconomic policies. Previous governments, all very business-friendly, were able to keep politics divorced from economics mostly because in the 2000s and 2010s there was an appetite for Latin American resources not seen since the end of the Second World War. This commodity boom, driven by China’s rise, allowed Peru to accumulate high levels of reserves, grow almost 6% annually for years and reduce poverty to 20% from the 50% recorded in the early 2000s. It also let governments ignore repeated warnings that secondary reforms would be necessary to maintain economic performance.

Already by 2014, for example, the IMF and World Bank were stressing the need for Peru to have a broader tax base, to modernize its labor market in order to incorporate more workers into the formal sector, to invest in technology and to diversify its economy so that it reduced its reliance on mineral exports, which make up about 10% of the country’s GDP. None of these things occurred.

Neither was any previous government able to provide a definitive solution to the social conflicts that have repeatedly arisen around mining projects in the last decade. Relationships between mining companies and the communities that live in their vicinity have become increasingly frayed. The Las Bambas copper mine, owned by MMG, was recently paralyzed for almost 50 days, despite the government’s several attempts at brokering talks between the population and the company. However, protests have been occurring since 2015, and in general, the inability to resolve the social conflict issue has now resulted in a smaller pipeline for mining investment in 2022.

What’s interesting is that Castillo’s new minister of Finance, Kurt Burneo, a well-known technocrat, has publicly recognized the need to recuperate investor confidence in order to foster economic growth. Two weeks ago, while presenting the budget for the next fiscal year, Burneo stressed that one of the government’s goals is to recover this confidence by promoting private investment through commissions that fast-track projects and government-to-government arrangements like the one with the United Kingdom for the 2019 Panamerican Games. Burneo has also stated that the ministry will not seek to increase taxes in a similar effort to reassure investors.

The Castillo government, thus far, has not proved to be the threat to the private sector that it was feared to be. In fact, it has largely maintained the same fiscal and macroeconomic management that’s been in place since the structural adjustment policies implemented in the 1990s.

And yet, macroeconomic discipline alone cannot foster the conditions necessary for Peru’s development. Politics was eventually bound to catch up to the economy. Unfortunately, it has coincided with a highly incompetent president at the helm, adding fuel to the fire.