This article marks the launch of the third edition of the Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC) Index produced by the Americas Society/Council of the Americas and Control Risks. Click here to read the 2021 CCC Index report.

The presidents of Mexico and Brazil have very different ideologies, but they are united by at least one belief: That they have eradicated corruption in their governments.

“I can say there is no corruption. It’s over because the president is not corrupt, and he doesn’t tolerate the corrupt,” Andrés Manuel López Obrador said at his daily press conference in March. Similarly, Jair Bolsonaro told reporters in October that he had ordered an end to Lava Jato, the country’s iconic graft investigation, because “there’s no more corruption in the government.” He added, with a touch of irony: “When I indicate any person for any position, I know he’s a good person, especially looking at the amount of criticism he receives from most of the media.”

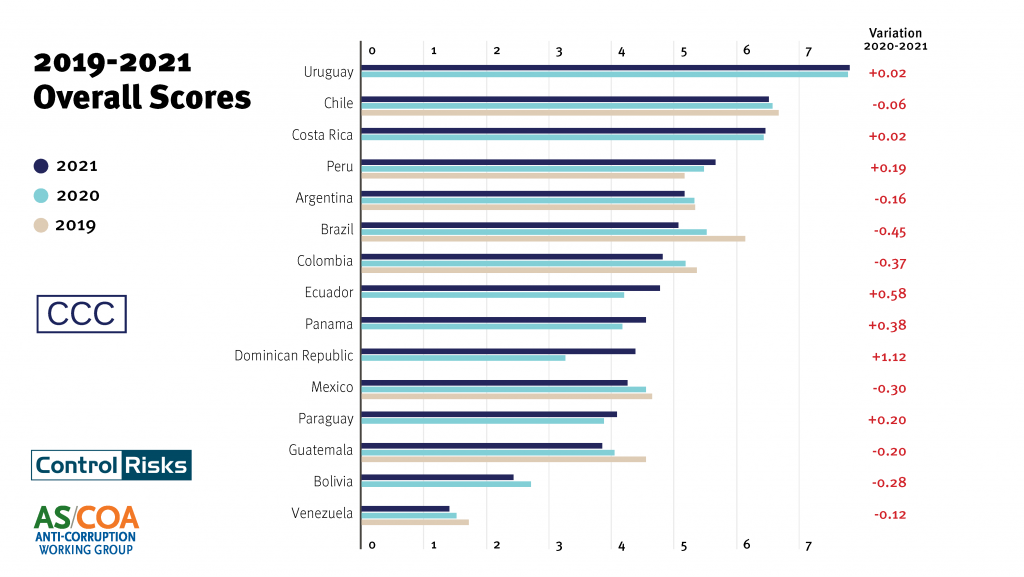

The 3rd annual edition of the Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC) Index tells a different and more complex story. Rather than measuring perceived levels of corruption as other studies do, the CCC Index evaluates and ranks 15 Latin American countries based on their ability to uncover, punish and prevent corruption. The index, which is jointly published by Control Risks and the Americas Society/Council of the Americas (which publishes AQ), draws on publicly available data as well as a proprietary survey that asks in-region experts to assess a variety of factors including the independence of courts, the strength of democratic institutions and the freedom of investigative journalists. Unfortunately, the 2021 edition of the CCC Index shows a decline in the anti-corruption environment in the majority of the countries surveyed. Brazil and Mexico were among the countries that saw their scores fall the most compared to 2020.

It’s not just a tale of individual leaders or governments, of course. Anybody who lives in Latin America, or does business there, knows that anti-corruption efforts have lost momentum since the mid-2010s, when Lava Jato and similar probes sent numerous powerful politicians and business leaders across the region to jail. Since then, the perceived errors and abuses committed by a number of high-profile prosecutors and judges have contributed to a decline in popular support for investigations in some countries. As a result, politicians have seized the moment to weaken corruption-fighting institutions and safeguards. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic led governments, citizens and civil society to shift their focus to other urgent priorities like the economy – despite numerous high-profile scandals involving the procurement of medical supplies and medicines.

But just as important as the pandemic is the widely documented erosion of democratic institutions occurring throughout much of Latin America and indeed the world in general. The CCC Index detected a concerning decline in the efficiency and independence of anti-corruption agencies in almost all the countries surveyed. The aforementioned statements from the presidents of Mexico and Brazil reflect an emerging (or “re-emerging,” if one takes a longer view) belief that strong leaders are single-handedly capable of purifying their countries’ politics. But we know from painful experience that this never works over time. Mexico saw its score in the CCC Index’s legal capacity category decline 8% this year, and it finished ahead of only Venezuela and Bolivia in the variable assessing the independence of the chief public prosecutor. Brazil suffered similar declines, following Bolsonaro’s appointment of figures perceived as less independent to the Federal Police and the Federal Public Ministry.

The news wasn’t all bad. The Dominican Republic saw the biggest increase in its score, by more than a point, after President Luis Abinader appointed an attorney general widely perceived as independent. Anti-corruption enforcement also appears evenly applied – in February, Abinader fired his former health minister over the alleged purchase of overpriced medical equipment. Ecuador and Panama also saw their scores rise, following concerted efforts by governments and civil society to crack down on graft, money laundering and other ills.

But the overall trend is clear, and disconcerting. Latin America has been one of the world’s regions hit hardest by the pandemic, which continues to leave a trail of death and economic destruction. Cleaner government would allow for more agile and effective responses to the numerous socioeconomic and health maladies that are likely to endure for years to come. Greater transparency would also help facilitate the boom in investment Latin America so badly needs, considering that foreign direct investment fell an estimated 50% in 2020, more than in any other region of the world.

None of these changes can be imposed from the outside – civil society, business leaders, politicians and other local actors will have to lead the process. But it’s certainly possible to get the virtuous circle of healthy democracies and economies started again. Combating corruption more effectively, with strong and independent institutions front and center, building on the growing maturity of compliance in the private sector, would be a good place to start.

__

Aalbers is a partner at Control Risks

Winter is the vice president for policy at AS/COA and editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly