Correction appended below.

RIO DE JANEIRO — On most Friday nights, 22-year-old Nathália Rodrigues finds herself bombarded with confessions from her online followers. Proclamations of late-night pizza orders and impulsive shopping sprees pour in from around Brazil, all of them followed by the words “Nath, I have failed you.”

The phrase has become something of a meme in Brazil, a testament to the popularity of Rodrigues’, aka Nath Finanças’ (Finances), brand of personal finance management. As one of the country’s most popular financial influencer-educators, Rodrigues has become something of a guiding light for a class of newly-banked lower-class Brazilians thirsty for financial education.

“My mission is to teach people personal finance in a way that is simple and easy to learn,” Rodrigues told AQ. “Real finances for real people.”

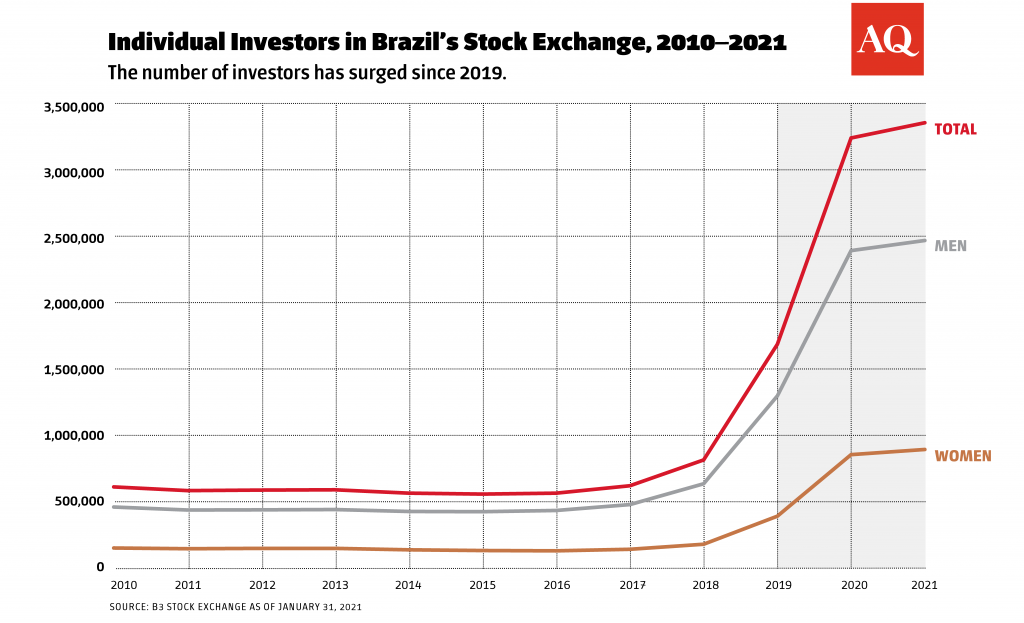

Rodrigues’ rise comes just as a surge of young and lower-to-middle class Brazilians has begun to invest in the stock market. Brazil’s B3 stock exchange data shows two million Brazilians invested for the first time between April 2019 and April 2020. The total number of individual investors now stands at over 3.3 million.

Launched in 2019, Rodrigues’ YouTube channel featured everything from simple explanations of Brazil’s basic interest rate, the Selic, to low-budget spending guides for Carnival, and gained a promising audience in the low thousands. But it was the pandemic — and some help from a rueful Dexter’s Laboratory meme — that swept her to stardom.

Within months of COVID-19’s arrival in Brazil, her following had doubled: By the end of 2020, Nath Finanças had 200,000 YouTube subscribers and 430,000 Twitter followers. Rodrigues earned her own column in the Extra newspaper and became a regular feature in Brazilian print, online and TV media.

She even has her own plug-in on Google Chrome. Install it and you’ll find your impulsive online purchases stuck behind a new barrier: Hover your mouse over a website’s “buy” button, and you’re beaned with an image of an inquisitive Rodrigues, the question “ARE YOU SURE YOU NEED THIS?” overlayed in all caps.

Her brand of simply-taught financial literacy for lower-class Brazilians hit the right note at the right time. Congress had just passed a bill authorizing monthly support payments of $105 for low-income workers, charging state-owned bank Caixa Econômica Federal with opening digital bank accounts for more than three million Brazilians. Online shopping surged, and by October, Brazil’s “unbanked” population had plummeted 73%.

Part of Rodrigues’ pull among what she calls “real” Brazilians is her upbringing in Nova Iguaçu, a city in the periphery of Rio de Janeiro. Born to a family that spoke little of money (“only at the end of the month, when there was never enough of it to pay the bills”), Rodrigues learned the dangers of financial illiteracy firsthand, paying exorbitant banking fees and falling prey to predatory credit card offers.

It was only after she began a degree in administration — finding time between coursework in financial mathematics and an internship at a financial firm in downtown Rio — that Rodrigues managed to pull herself out of what had become a classic credit card debt spiral. Soon, she began envisioning free financial education for Brazilians like herself. Thus was born Nath Finanças.

As the online “coach” community began peddling stock market “Get Rich Quick” schemes, Rodrigues stuck to her principles, dissuading her followers from jumping in until they had gotten their bills in order. “My audience is not a audience that is prepared to invest. It is a audience that is in debt. And I get tons of questions on social media about how to get rich quick and how to invest,” said Rodrigues. “I say look, guys. Let’s stop and think. Are you still in debt? Yes? Then why are you getting into the stock market?”

Credit: Nath Finanças

“I’m not here to talk to people about how to invest a thousand reais. I’m here to teach them how to save ten reais. Because sometimes, for my audience, that’s all that’s left at the end of the month.”

Tatiana Lima, a journalist from Rio’s North Zone, said that Nath Finanças helped her realize how much she was paying in monthly fees at a traditional bank. “I closed that account and opened one with a digital bank, with no costs,” Lima told AQ.

Rodrigues said that, for many, access to new technologies like digital banking has provided a welcome change. “They found a way to reach lower-income Brazilians that were tired of dealing with traditional banks, waiting two hours in line to pay their bills,” said Rodrigues.

But despite the benefits of fintech, Rodrigues worries that there has been no concerted public education plan to guide millions of new users (many of them only recently banked) through the incipient technology. “When I went online to explain how to use [the new Central Bank payment system] PIX, I had more than 100,000 viewers.”

For Rodrigues, it may take time for Brazilians to forget past financial sins. “We have a past full of pain,” she said, pointing out that President Fernando Collor de Mello confiscated close to $100 billion from Brazilian bank accounts in 1990, essentially destroying confidence in the banking sector. “These are people that to this day haven’t gotten their money back. So we have this justified insecurity and fear about saving money.”

A previous version of this article misstated the number of investors in 2019