On February 1, the Trump administration accused Mexico’s government of maintaining an “intolerable alliance” with drug trafficking organizations—an allegation Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum immediately dismissed as “slanderous.”

The White House provided no new evidence to support the claim, perhaps because proof is somewhat elusive. Despite cases of narco-corruption in past governments that reach all the way to the top—like the conviction of ex-federal security secretary Genaro García Luna in U.S. federal court on drug trafficking charges—there is no “smoking gun” evidence that recent Mexican presidents have themselves forged pacts with drug traffickers or personally authorized them.

But President Trump could have easily pointed to a long list of Mexican governors and mayors convicted for organized crime ties. In the past decade, Mexico has imprisoned five former governors for connections to organized crime, while the U.S. has extradited two others. The list of former mayors jailed on charges of colluding with organized crime is even longer.

This is what should most worry Trump, Sheinbaum, and other regional leaders: crime’s growing influence at the local level—the product of crucial shifts over the past 15 years.

During the 2010s, crime groups throughout the region recognized that penetrating city halls and governor’s offices was easier and often more effective than targeting the presidency or Congress. Without transforming entire countries into narco-states, their influence is eroding democracy, the rule of law, and investment conditions across large swaths of their territories.

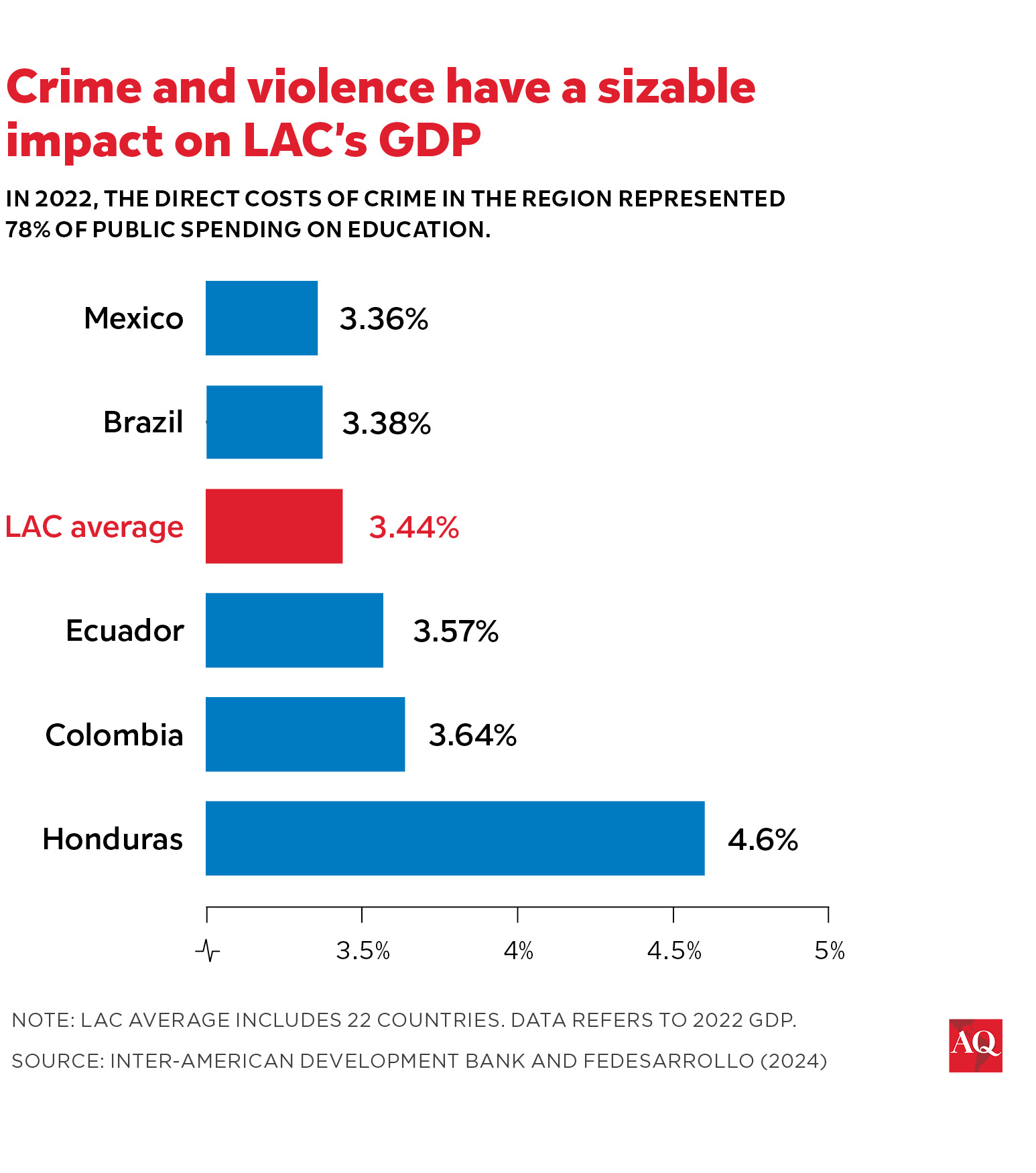

The direct costs of crime and violence in Latin America reached 3.4% of the region’s GDP as of 2022, according to the IDB. Presidents must prioritize limiting crime’s local influence before it spreads further, even if it means confronting members of their own parties.

Going local

Until the 1990s, when drug traffickers sought to buy off or intimidate political power, they typically aimed for the top, injecting drug money into national campaigns and assassinating ministers and presidential candidates. They haven’t entirely given up on this strategy, as recent high-level convictions, like that of Honduras’ Juan Orlando Hernández, prove.

But in many parts of the region, crime has gradually recalibrated its political tactics, becoming more efficient and, above all, more local. During the 2010s, thanks to soaring global demand, cocaine, illegal gold, and migrant smuggling boomed like never before. Those booms, coupled with government crackdowns, produced what I have called “reorganized crime”—a fluid, ultra-competitive mosaic of old and new crime groups vying for influence.

“Reorganized crime” meshed naturally with Latin America’s increasingly competitive local politics. With the decentralization of the 1990s and 2000s, mayors, governors, and local assemblies came to hold real power, including control of local police and lucrative public contracts. Campaigns for local office became increasingly costly, and the political machines and strong national parties that had traditionally financed and organized them in many places weakened. Reorganized crime filled the sizable gap.

Parallel power

Across parts of Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Central America, crime has come to constitute a “parallel power” at the local level. It is parallel in the sense that it exists side by side with the state, has its own (illicit) revenue streams, and can either collude, combat, or simply coexist with local authorities—whatever is best for business.

Like parallel political parties, crime groups in these areas finance campaigns and hold their own de facto primaries, pressuring candidates to drop out or simply eliminating them. In Chiapas and Michoacán—two of Mexico’s most crime-ridden states—ten candidates for local office were killed during the 2024 general elections and hundreds more dropped out before election day. Like parallel election administrators, crime groups may remove and replace party activists involved in supervising the vote, as occurred in 2021 in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, where dozens of opposition party activists were kidnapped.

Before and after election day, crime groups also negotiate and renegotiate secret deals with the winners, often through public shows of force. Where these deals stick, they repurpose public administration as a tool for administering their criminal businesses. Public contracts become channels for laundering crime money. Property title offices legalize ill-gotten assets. Sometimes, they enlist local police. According to reports in local newspapers, Brazil’s two largest gangs, the First Capital Command (PCC) and the Red Command (CV), have mastered these arts.

The costs of local control

Criminal influence in local politics is arguably less catastrophic than a full-blown narco-state. But this makes it all too easy for presidents to neglect the problem. In Colombia, killings and violent threats against political leaders have nearly tripled from 2015 to 2023. Similar, if not larger, increases have been registered in Mexico and Brazil. In all three countries, the victims are almost always municipal or state government officials.

Crime’s local power erodes democracy and the rule of law. In cities and states where crime groups loom large politically, voters often cannot be certain about who they are really electing, since candidates may have hidden criminal backers. They cannot trust that candidates are competing on a level playing field, or if the press is genuinely free, given the immense pressure on journalists to self-censor. Nor, in these areas, can they count on the local justice system. In Mexico’s Guerrero state, for instance, where crime and politics are tightly interwoven, more than half the employees of the state prosecutor’s office required to submit to background checks either refused to do so or failed them. A string of active duty and former prosecutors have been killed there since 2023.

Meanwhile, legal economies and investments suffer. In Sinaloa, Morelos, and Tamaulipas, three Mexican states in which crime groups loom especially large, foreign direct investment has fallen below pre-pandemic COVID-19 levels.

Rio de Janeiro state’s energy distribution company, Light, was compelled to file for bankruptcy on May 12, 2023, after militias and armed groups described by Justice Minister Flávio Dino as being “protected by (local) politicians” stole its products and imposed exorbitant unofficial fees on its users.

In Brazilian cities with high homicide rates, companies invest less in their workforces and research and development. A recent IMF study indicates that halving homicide rates in violent municipalities could increase their economic output by 30%. Reducing crime’s grip on local politics could pave the way for growth.

Taking action

To address the challenge, the region’s presidents and top prosecutors must investigate governors and mayors who collude with crime, hold them responsible and offer adequate protection to those who resist. For now, Brazil is leading the way, even as crime groups’ push into local politics there remains a major problem. In 2023, federal police dismantled a criminal plot to kidnap and kill authorities across five states, and last year, authorities froze organized crime funds intended to finance local candidates in municipal and state elections.

But politics often gets in the way. Presidents risk losing legislative support and fracturing their own parties by boldly going after corrupt state and local officials. In Mexico, the Guacamaya leaks—a cache of military documents hackers made public—provided evidence that military intelligence believed at least three governors from the ruling Morena party either staffed their administrations with organized crime figures or cut deals with cartels. But Mexico’s federal prosecutor’s office hasn’t launched any follow-up investigations. Each governor has denied the allegations.

Reorganized crime doesn’t need full-blown narco-states to thrive; it just needs to continue its push for local power. If Trump, Sheinbaum, and other leaders really want to weaken it, they must focus on reducing its political influence at the local level.