This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Lula and Latin America

BOGOTÁ – As an anti-corruption crusader, Iván Velásquez faced down drug lord Pablo Escobar, exposed ties between Colombian politicians and death squads, and was declared persona non grata in Guatemala after helping to put that country’s president behind bars. But his current assignment as Colombia’s defense minister may prove his most challenging post.

Velásquez accepted the job, which involves managing the 481,000-member armed forces and national police, even though he had no experience in security matters; he was better known for denouncing human rights violations, including cases involving the Colombian military. His appointment last August dismayed an officer corps already alarmed by the 2022 election of President Gustavo Petro, a former left-wing guerrilla. Then, just days into the job, Velásquez launched a massive reorganization that led to the ouster of more than 50 generals and admirals.

“It would be hard to think of a defense minister who would be more offensive to many elements within Colombia’s military” than Velásquez, said Jeremy McDermott, co-director of Insight Crime, a think tank that researches organized crime in Latin America. “This was an earthquake for the security forces.”

Amid the aftershocks, Velásquez must address Colombia’s complex and shifting security landscape.

On the positive side, Colombia’s homicide rate has decreased slightly and there has been a notable lack of scandals involving the police and military under Velásquez, said Jorge Restrepo of the Bogotá-based Resource Center for Conflict Analysis. That has been a welcome change in a country where security forces have been repeatedly accused of illegally killing civilians, corruption and the use of excessive force, including at 2021 protests against Petro’s predecessor, Iván Duque. The purge of the officer corps, Restrepo added, cashiered many who opposed the Petro government’s peace initiatives.

“It brought a breath of fresh air into the armed forces,” Restrepo said. “The new military hierarchy is committed to human rights.”

Yet there is more to the story, especially outside Bogotá. Despite a historic 2016 peace accord that demobilized the FARC, Colombia’s largest guerrilla group, an array of smaller rebel factions and drug trafficking and crime groups continue to sow terror in large patches of the countryside home to 7 million people, or about 15% of Colombia’s population. These groups have no real ambitions to seize power and mainly fight among themselves over territory. But they are killing and kidnapping civilians, extorting businesses and forcibly recruiting young people. Critics say Velásquez’s decisions have stripped the security forces of some of their most experienced leaders.

“To me, it seems like a very dangerous situation to have a new defense minister without any knowledge of security issues who then gets rid of most of the military’s installed capacity to fight criminal groups,” said Daniel Mejía, a former government security secretary for Bogotá, Colombia’s capital.

Ceasefire confusion

Complicating matters further is President Petro’s reluctance to use military force as he attempts to negotiate ceasefires with Marxist rebels, like the National Liberation Army (ELN), and criminal groups such as the Gulf Clan. This is central to his signature policy of paz total, or “total peace,” which aims to immediately reduce homicides, torture and disappearances and, eventually, end armed conflict in Colombia.

But the policy has also been perceived as confusing. In some cases, troops have been told to cease “offensive operations” against these groups but to combat the cocaine trafficking and other crimes they carry out. This has left the armed forces unsure of the rules of engagement and hesitant to act, said Humberto de la Calle, a Colombian senator who was chief negotiator of the 2016 peace treaty with the FARC. Velásquez, he said, has further muddied the waters with “abstract” speeches.

“The armed forces are trained to obey orders, but Velásquez has failed to provide total clarity about their mission,” de la Calle said.

A prime example of the confusion came on March 2 when 5,000 armed protesters, whom local officials claim were infiltrated by guerrillas, took over an oil pumping station in southern Colombia to demand better roads and government services. They quickly overwhelmed anti-riot police, who do not carry firearms, killed one of them and kidnapped 78 others. Over their mobile phones, some of the officers pleaded for help, but the government refused to dispatch troops. Instead, Velásquez helped win the release of the officers through a day of negotiations. As he shook hands with the newly freed men, Velásquez said, “We managed to keep in check a very complex situation involving people who could have caused a lot more violence.”

But rather than applauding Velásquez for avoiding a bloodbath, some Colombians saw the episode as a sign of weakness. Meanwhile, videos of the kidnappers herding humiliated police officers into cattle trucks recalled the late 1990s and early 2000s, when rebels routinely captured police and army troops and had the upper hand in the war. In an editorial, the Bogotá newspaper El Espectador blasted the Petro government for applying “lots of carrot and very little stick” in the standoff and noted that “since Iván Velásquez arrived at the Defense Ministry, the news has been macabre.”

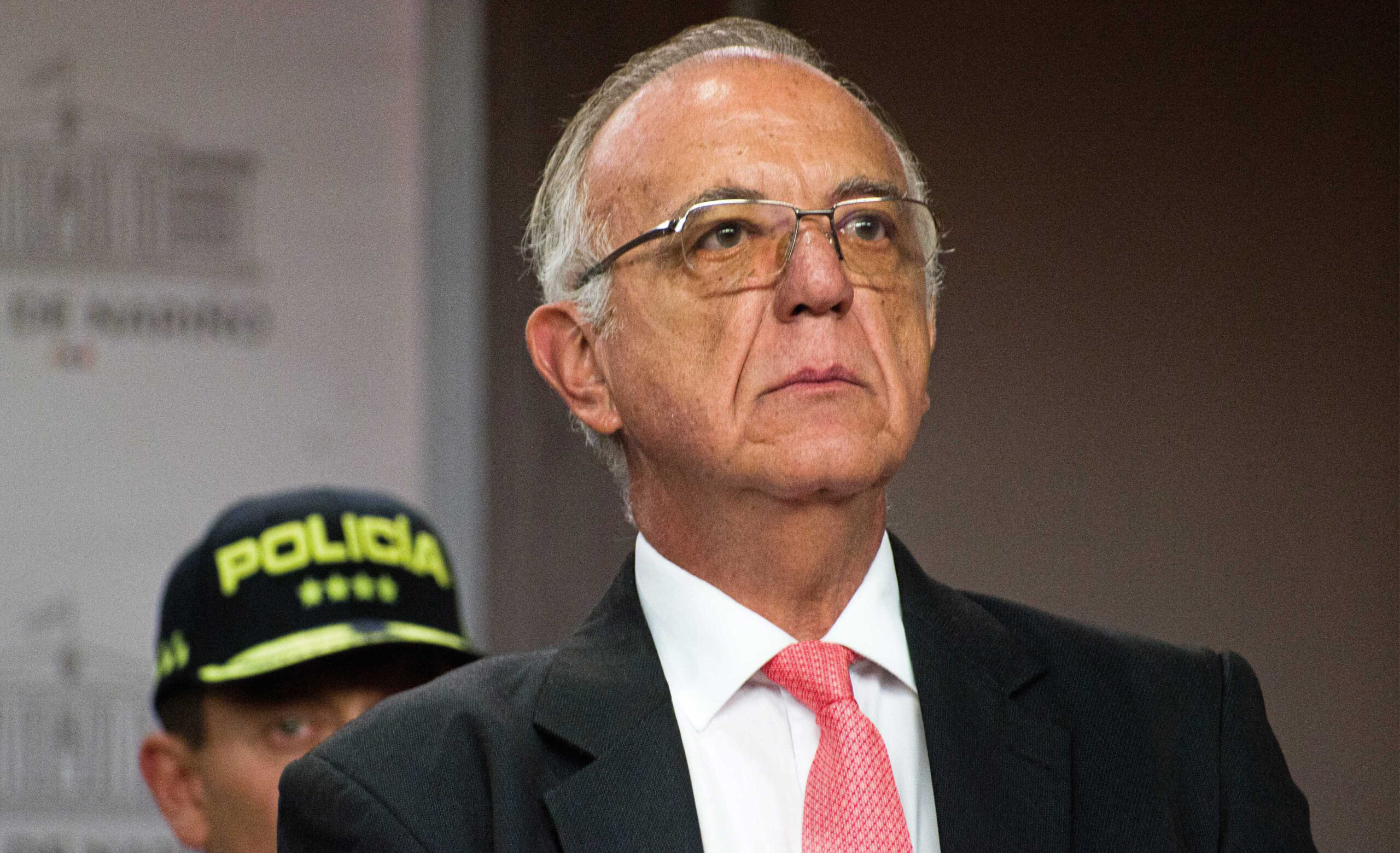

A spokeswoman for Velásquez said he was too busy to speak with AQ for this story. But at a recent news conference in Bogotá, he ticked off a list of ongoing military operations and bristled at suggestions the police and army were hunkered down in their barracks.

“We are not just sitting around with our arms crossed,” said Velásquez, looking somber in wire-rim glasses and a dark suit.

Decades of public service

Indeed, Velásquez, 67, has always been a workaholic and a deeply committed public servant.

He grew up in Medellín, studied law, and, as Colombia’s dual guerrilla and drug wars raged in the 1980s, focused on human rights cases. In 1991 he was appointed inspector general—the government’s internal affairs chief—for Antioquia department, a dangerous job as many state offices had been infiltrated by the Medellín Cartel. At one point, an envoy for Pablo Escobar offered Velásquez a suitcase full of cash to back off on his investigations. He rejected the bribe, but, fearing for his life, sought out the imprisoned drug lord to explain why. A sweaty Escobar, who was playing soccer on the prison grounds, halted the game to meet with Velásquez.

“I thanked him but told him I don’t accept gifts,” Velásquez told the Bogotá magazine Bocas in an interview last year.

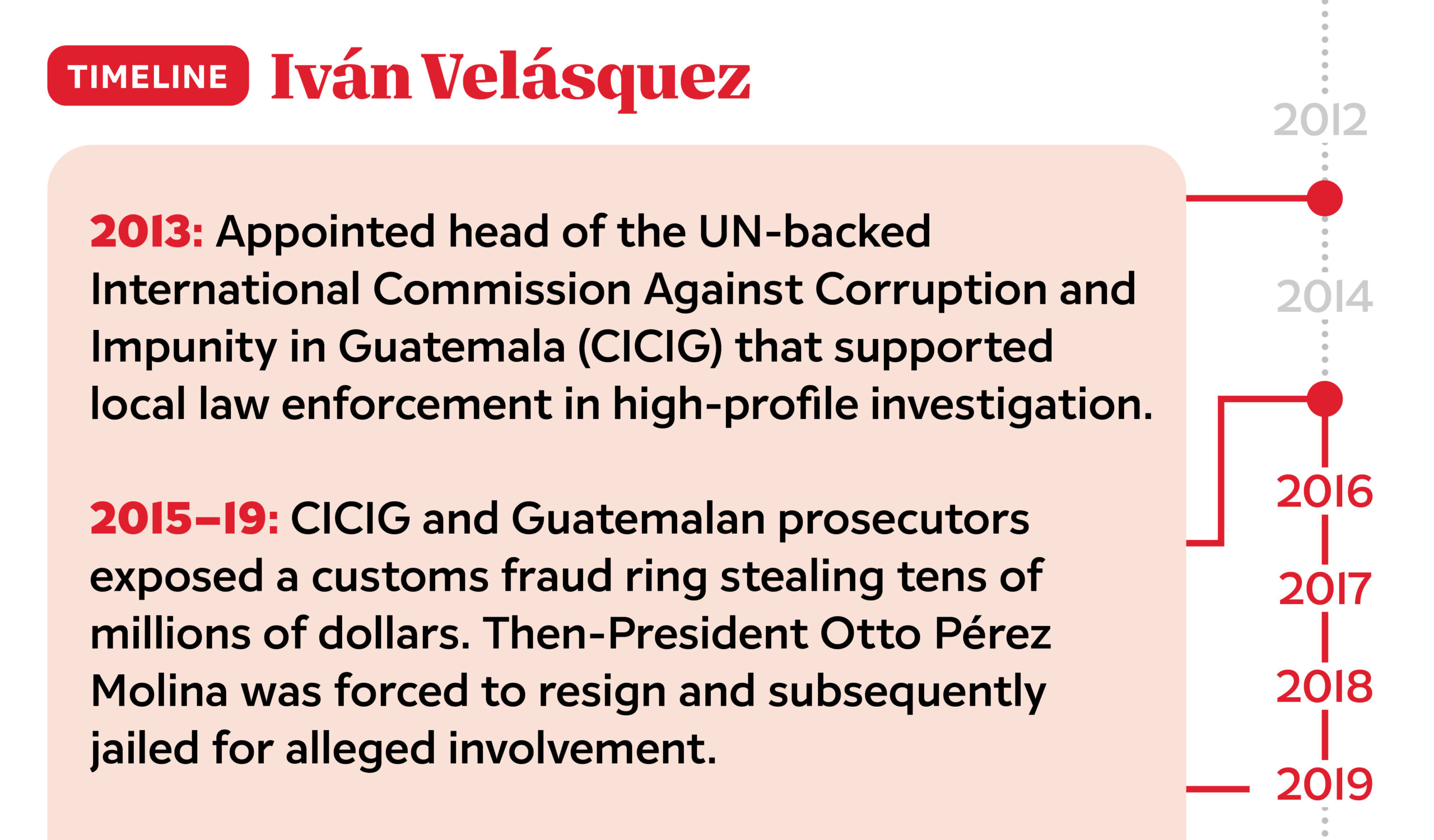

As an assistant justice on Colombia’s Supreme Court in the early 2000s, Velásquez investigated a wide-ranging conspiracy in which Colombian politicians were financing right-wing paramilitaries who then intimidated voters into supporting them during elections. The probe led to more than 60 convictions and caught the attention of the United Nations. In 2013, Velásquez was selected to head the U.N. International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala. Known as CICIG, it was formed in 2006 to help solidify Guatemala’s democratic institutions as criminal rings were infiltrating the country’s political system. As usual, Velásquez was all in.

“He slept in the same dark bunker where he worked, 24/7, and he could not step outside of his offices without a heavy armed guard,” wrote Maria McFarland Sánchez-Moreno in There Are No Dead Here, a book that details Velásquez’s work in Colombia and Guatemala.

In its most sensational case, the commission helped Guatemala’s judiciary with an investigation that led to the 2015 resignation of then-President Otto Pérez Molina, who was later convicted on corruption charges. Thousands marched in the streets to support the commission’s work while graffiti in Guatemala City proclaimed: “I love CICIG” and “Thank you, Iván!”

“In the past decade, Guatemala has become a place where once-untouchable, powerful elites have learned to fear criminal prosecution,” Velásquez wrote in a 2019 op-ed in the Washington Post.

Critics, however, say Velásquez overreached by targeting the family of President Jimmy Morales, sworn-in shortly after Pérez Molina resigned, over comparatively minor corruption allegations. An enraged Morales, himself under investigation for illicit campaign financing, declared Velásquez persona non grata and, in 2019, forced the CICIG to shut down.

Velásquez’s reform agenda

Back in Colombia, after Petro squeaked out a victory in the 2022 presidential election, Velásquez seemed like a natural for justice minister. But Colombian presidents often put political heavyweights in charge of defense, and Velásquez was a highly respected figure both at home and abroad. His selection also signaled that the new president would have zero tolerance for abusive behavior by the police and military, said Adam Isacson, a Colombia expert at the Washington Office on Latin America.

A clean-up job was in order following multiple scandals, ranging from police killings of protesters to corruption allegations to army officers illegally spying on politicians and journalists. A report last year by Colombia’s Caracol TV found that 39 of the army’s 56 generals were under investigation by the Attorney General’s office. Most of them have now been cashiered.

Velásquez also wants to eliminate Colombia’s obligatory draft and overhaul the military contracting system, long a source of graft. His most ambitious plan is to separate the police from the Defense Ministry to turn a highly militarized force that spent decades battling guerrillas and drug traffickers into an organization focused on protecting citizens and dealing with protesters.

However, none of these reforms is likely to garner much support if security in the countryside continues to deteriorate. Efforts to reach ceasefires with the ELN are floundering. In March, reacting to a military offensive against illegal gold mining, the Gulf Clan—Colombia’s largest crime organization—attacked police stations, blocked highways and paralyzed commerce in parts of Antioquia and Córdoba departments. In a February survey by the Invamer polling agency, Petro’s job-approval rating had dropped to 40% as pressure mounted for his government to adopt a harder line.

“Today, no armed group in Colombia feels a threat of such magnitude from the military or police that it would be inclined to offer real concessions,” says a new report from the International Crisis Group. “The Petro government urgently needs to complement its plans for dialogue with a more rigorous security approach.”

Velásquez suggests this could backfire and referred to his successful efforts to free the 78 policemen abducted at the oil station. Had he sent in the troops, there would have been a shootout. Then, instead of calling him out for going soft on criminals, he said, critics would accuse him of provoking a massacre. Speaking to Medellín’s El Colombiano newspaper, he said, “We must figure out ways to exercise authority while also respecting human lives.”

For Colombia’s defense minister, finding that formula remains a work in progress.