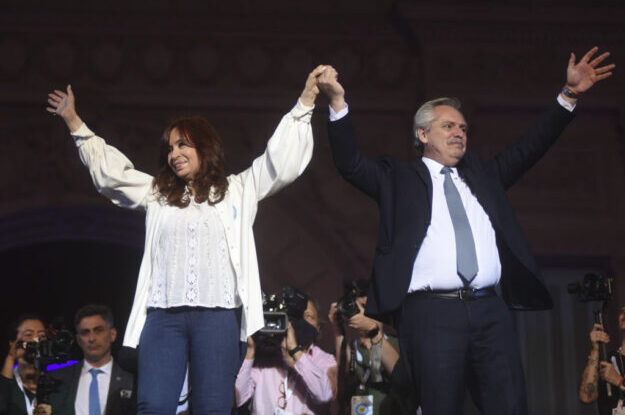

In an interview with La Nación published on December 8, Argentine President Alberto Fernández declared “I am the one who decides.” Meanwhile, his powerful vice president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner wrote in an open letter that she “is not the one holding the pen” regarding the potential of a much-heralded upcoming deal with the International Monetary Fund. Is there a new détente between the Peronist partners in power – or is this just another temporary truce?

It’s a vital question for the future of Argentina, bruised by the pandemic and with inflation running near 50%. The ruling Frente de Todos coalition, weakened by a bruising electoral defeat in November midterm elections, needs all its disparate elements in Congress to work together in order to support the IMF agreement, an effort that suffered a reverse on December 17 when the lower house rejected the government’s budget proposal. Cristina Kirchner’s influence and negotiating role as president of the Senate will be in much need as the Peronists, a minority though still the largest party, will need votes from a third party, Juntos Somos Río Negro. But will she play along? After all, her words – “Cristina isn’t the one holding the pen” – can be interpreted in several different ways.

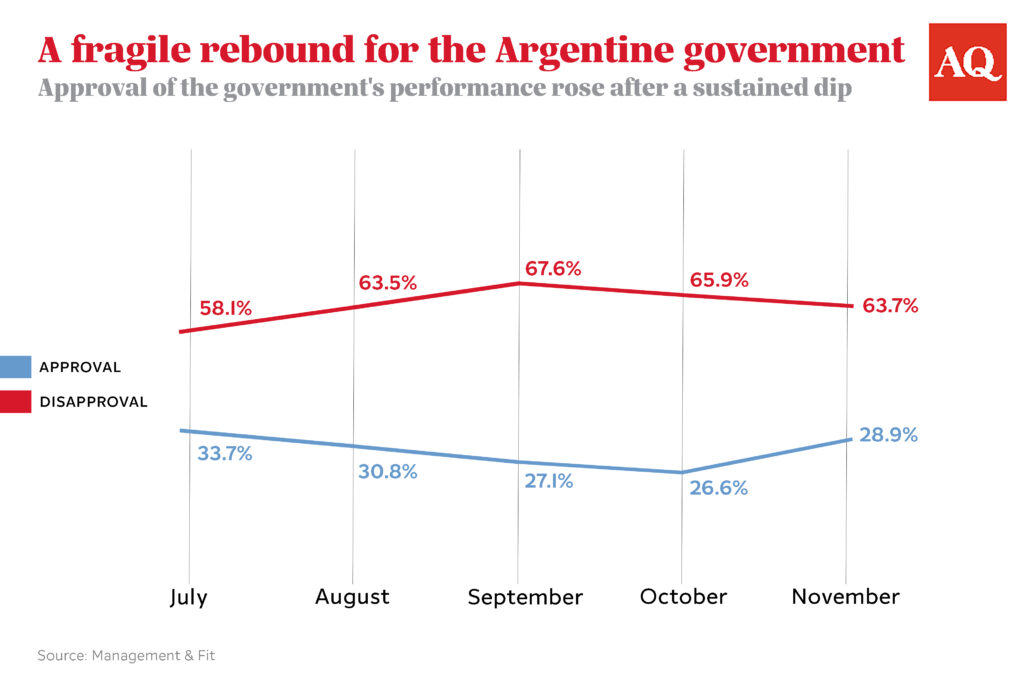

The Peronist dust-up before November’s elections is still fresh in everyone’s minds. After primary results came in looking disastrous for the government in September, Kirchner penned a devastating open letter asking Fernández to fire several ministers and reverse course on spending cuts. But matters have cooled since. Fernández met Kirchner halfway, firing his chief of staff but keeping his economy minister, Martín Guzmán. That didn’t stop the government from suffering a defeat, losing its majority in the upper house, but the damage wasn’t quite as bad as the primaries had suggested.

A slightly worse than expected result for the opposition coalition Juntos por el Cambio has now sparked tensions there as well. “Since the notable and underappreciated victory on November 14,” writes Sergio Berensztein in La Nación, “the principal opposition leaders have behaved in a way that is dangerously similar to (past opposition defeats).” The Unión Cívica Radical is embroiled in internal tensions, including opposition to the head of the Juntos por el Cambio bloc in the lower house, Mario Negri. Meanwhile, PRO party president Patricia Bullrich had to clarify her remarks complaining about the opposition missing its target of 50% of the vote in Buenos Aires, perhaps to avoid seeming to blame PRO-affiliated Buenos Aires mayor Horacio Rodríguez Larreta.

Who came out of the November elections ahead, Cristina or Alberto? For Maria Esperanza Casullo, a political scientist at the National University of Río Negro, it certainly strengthened Cristina. “Before the elections, she said, ‘We need to put more money into people’s pockets right away, you need to fire some ministers.’ … And he did.” But it wasn’t all one-sided: “Alberto probably feels that he was able to run a better, more disciplined campaign” than many expected following the reshuffle, navigating the relationship with Cristina effectively.

Juan Cruz Díaz, a political analyst, has a positive view on the whole exchange. “I think with that letter, Cristina channeled discontent (within her faction) in a quite orderly way,” he says, compared to past instances of violent discontent in the streets. Seen in this light, Cristina Kirchner has a difficult task to fulfill within the ruling coalition: She must corral the left-wing groups in her orbit to support, at least reluctantly, government policies they may not like. Perhaps her letter, by registering discontent and obtaining concessions from the president, was a counterintuitively effective means of doing so.

These are the challenges that face a Peronism now operating in uncharted territory. The movement long relied on powerful central figures — such as Juan Perón, Carlos Menem, Cristina’s late husband Néstor Kirchner and, during her stint as president, Cristina Kirchner herself. But she is no longer such an overpowering figure, and now Peronism must function as a big tent that harbors several competing forces. With Fernández’s election, “a Peronism usually described as vertical and personalistic (became) a coalitional structure,” says Casullo. Many political parties that function as coalitions, such as the Democratic Party in the U.S., have familiar or institutional means of picking winners and disciplining losers of internal clashes. But the Frente de Todos bloc lacks such institutional channels, and so the sorting out of internal debates relies on personal relationships — and, in turn, on everyone involved keeping their heads.

That is being put to the test now, as the government’s budget has been rejected by the lower house, creating uncertainty in the path towards a deal with the IMF. Critics had complained of cuts to spending in critical areas including education, where spending was projected to drop by 6.2% in the initial budget proposal. Provincial governors had demanded more subsidies for transportation outside the capital.

Will recent signs of goodwill continue? An Argentine delegation met with IMF staff in Washington on December 10 and issued a cordial statement. After the budget was rejected, Kristalina Georgieva, the Fund’s managing director, took a reassuring posture, tweeting on December 17 that she had had a “very good meeting” with Alberto Fernández. There’s a sense of mutual desire to come to a satisfactory agreement – Argentina wants to avoid another default, and the IMF, having made an exceptionally large loan to the country under Mauricio Macri’s government, sees its own reputation on the line.

Meanwhile, Cristina Kirchner has been “quite quiet” in recent weeks, says Díaz. Yet back-to-back rallies by pro-government and anti-IMF demonstrators in Buenos Aires during December 10 and 11 seemed to suggest that Cristina will experience pressure from left-wing groups in her orbit to reassert herself in the negotiation process. The crucial question, one that only she may be answer, is whether she can resist it, or sublimate it in a minimally harmful way – and whether she wants to. All sides seem to want a deal, but if the history of Argentina is any indicator, further bumps in the road seem inevitable.