BUENOS AIRES – Nearly 55% of the world’s lithium deposits lie in Latin America’s lithium triangle, the swath of territory encompassing Chile’s and Argentina’s northern regions and Bolivia’s southwest.

But as hopes of a windfall from increased electric vehicle production rise, anxieties are rising too over which country will come out on top—or whether cooperation between the three can help secure more advantageous deals.

Already, expectations of rising demand are contributing to strains in global supply, as the price of lithium carbonate equivalent, a key lithium derivative, has soared almost 500% in the past two years. The International Energy Agency expects demand to rise to 2.5 million tons by the end of the decade, up from 0.5 million today.

Electric passenger vehicles sales are projected to hit 21 million units in 2025, BloombergNEF has estimated, a jump of nearly 220% compared to 2021. Global automotive companies such as Toyota, which owns a joint venture which produces lithium carbonate in Argentina, are looking to secure their supply in the lithium triangle.

Competition—or collaboration?

Chile, Argentina and Bolivia could become major global lithium players by the decade’s end. But there are risks that supply could falter if production is not streamlined. Unlike OPEC for oil, the region lacks a coordinated approach to set policy and influence global prices. The majority of lithium extraction is carried out by foreign or private miners, and there is little synchronization at the country level.

“Global interests (in lithium) are so big that if we do not manage ourselves in a very strategic way, we could not benefit as much as we really want,” Carlos Ramos, president of Bolivia’s national lithium company, Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB), said in an interview with local media.

Some agree that the region could land better deals if the three countries worked together. And timid steps have been taken in that direction. In August, Chilean and Argentine state secretaries met to discuss a “strategic approach” to develop the lithium value chain and agreed to have a trilateral meeting with Bolivia, though no specific date was given.

A CELAC summit held in Buenos Aires from October 24 to 26 featured conversations on lithium collaboration.

Argentina seems most interested in collaboration that could lead to a standard price for the metal. Local media had recently reported that the government was pushing the idea of a regional lithium association that could resemble OPEC’s powerful grip on global oil prices.

But after the Argentine government claimed that the countries’ foreign ministers were meeting to work on a joint document on regional lithium policy, provincial governors complained and the meeting ended with no agreement—providing the latest illustration of the difficulties that attend international collaboration on lithium.

It is unclear how supportive both Chile and Bolivia’s governments are of such an initiative. Moreover, the decision to coordinate production at a trilateral level could clash with Argentina’s own laws, which dictate that natural resources are owned by its provinces, which have successfully drawn massive private capital and could be reluctant to share the benefits more broadly.

At any rate, coming to terms around policy will be a daunting task, considering Bolivia’s low production levels as of yet, and the leading role played by private enterprise in extraction in Argentina and Chile.

In Chile, memories of the Intergovernmental Council of Copper Exporter Countries are not encouraging. In the late 1960s, the country was one of the founders—together with Zambia, Peru and Zaire—of an organization that sought to coordinate policies around the red metal. The alliance was ultimately abandoned decades later as its efforts to control global copper prices proved unsuccessful.

Extracting lithium in South America

Of course, any potential agreement between lithium producers in Latin America must take into account the realities of production in the region—and a shifting balance between countries.

Outside South America, lithium is usually extracted from hard rock. In the region, it is found in salt-rich water that is pumped to the surface into an evaporation pond. The sun takes it from there. This method is cheaper, but takes longer to produce results.

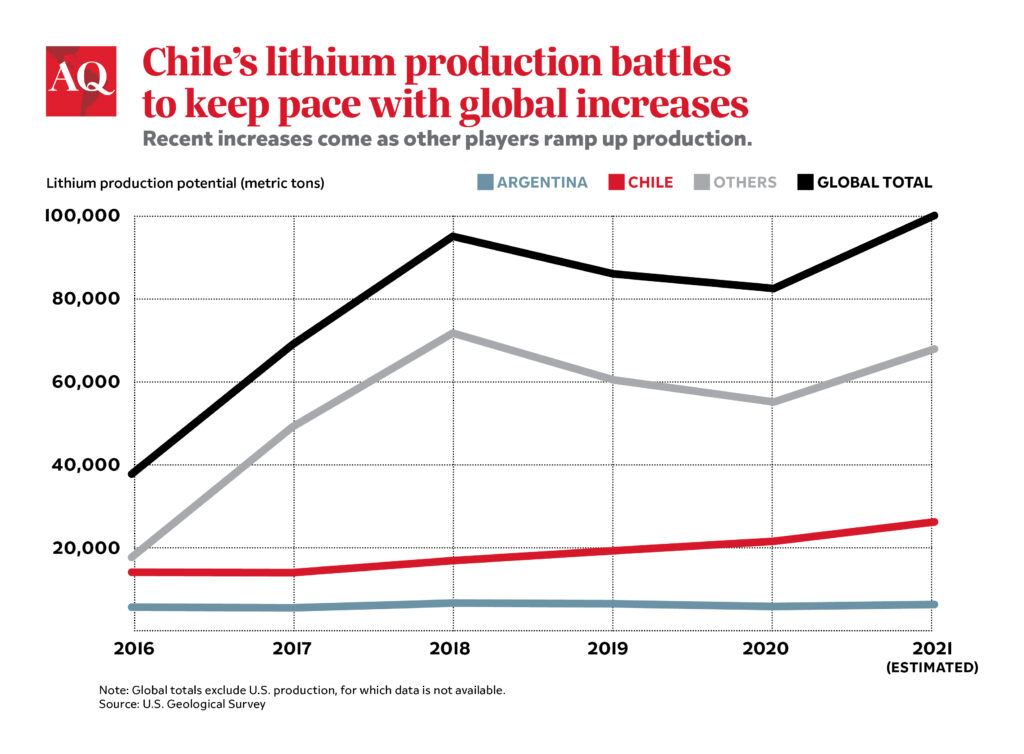

Chile, which has been mining lithium for years, is Latin America’s largest player. In 2021, it produced 26,000 tons of lithium, a quarter of the world supply, second only to Australia (55,000 tons). China is the third-largest producer, with 14,000 tons, and Argentina comes fourth with 6,200.

But according to data from the U.S. Geological Survey, Bolivia and Argentina have the world’s largest identified reserves, 21 million tons and 19 million tons, respectively. This is twice as much as in the U.S. or Chile, and three times as much as in Australia. It could provide the material for a shakeup in the national distribution of production in the region—but for now, this potential is mostly unrealized.

Argentina is seeking to expand its share of production. In the past two months, delegations of Argentine officials made three separate trips to the U.S.—including the president, the finance minister and governors—touting energy and lithium resources in the process.

“The world demands lithium and we have the opportunity to provide it,” President Alberto Fernández said recently, arguing that the country has “huge possibilities” to become a significant supplier.

Some experts agree Argentina is gaining momentum. Despite financial instability and a poor economic reputation, the country has drawn billion-dollar deals from investors. In July, Chinese Ganfeng Lithium bought rights over two lithium flat salts in Salta for $962 million. According to data from the Argentine Lithium Chamber, the country has only two mines operating. But more than ten new projects are being developed.

With the surge in global prices, Argentina’s exports have risen to $500 million this year. But they are well short of the $3.5 billion the government estimates it could get by 2030.

In Chile, lithium exports have risen dramatically to $5 billion from below a billion last year. In 2022, the metal is set to displace gold, silver, and iron altogether as Chile’s second-most exported mining product.

But some are concerned that the country might lose its leading position in the region, as prospects of an expanding role for the state in the sector may deter new investment.

“Chile cannot make the historic mistake of privatizing resources again and for this reason we will create a National Lithium Company,” then-candidate Gabriel Boric tweeted in December 2021. After he was sworn in in March, the government attempted to review contracts awarded to two giant lithium miners.

“It is evident that Chile’s share is going to fall,” Gonzalo Gutiérrez, Chile’s Lithium and Salt Flats Advisor to the Ministry of Mining, said in an interview. The government seeks to compensate for the lack of new projects with technological gains.

In Bolivia, the country has few exports yet to speak of, and both a higher altitude and a lower lithium concentration in its salt flats makes extracting the metal uneconomical without specific technology.

But with the largest identified reserves in the world, the effort could pay off. Some private companies are willing to take their chances. The country, which nationalized lithium in the late 2000s, mandates that YLB have a definitive say in all endeavors. More recently, however, it opened the door for private sector investment, with YLB exploring partnerships with foreign companies to develop the extraction technology.

Will one country come out ahead of the others in the struggle to profit from global demand for batteries, or will regional cooperation help bring shared prosperity? The direction of government will prove a decisive factor—but only time will provide a definitive answer.

—

Feliba is a financial reporter covering Latin America. He has written for the Washington Post, the New York Times and S&P Global Market Intelligence among other publications.