Hopes that an election in Venezuela next year might resolve the country’s political divisions and revive a moribund economy have reemerged as the Biden administration and Nicolás Maduro’s regime are reportedly near an agreement to lift some U.S. sanctions in return for steps to hold a fair contest in 2024. Still, considering recent history, skepticism abounds among the international community that the authoritarian government would allow an opposition candidate to win the election and take office.

Within Venezuela, however, there is a surprising level of faith in the potential of elections to bring political change and restore democracy. Over the past few months, the response to the regime’s politicization of the electoral council, banning of leading candidates, and efforts to disrupt an opposition presidential primary has been one of defiance. An independent commission is proceeding with preparations for the primary, candidates are crisscrossing the country and campaign headquarters are bustling. And in another encouraging sign, civil society groups are educating and mobilizing voters.

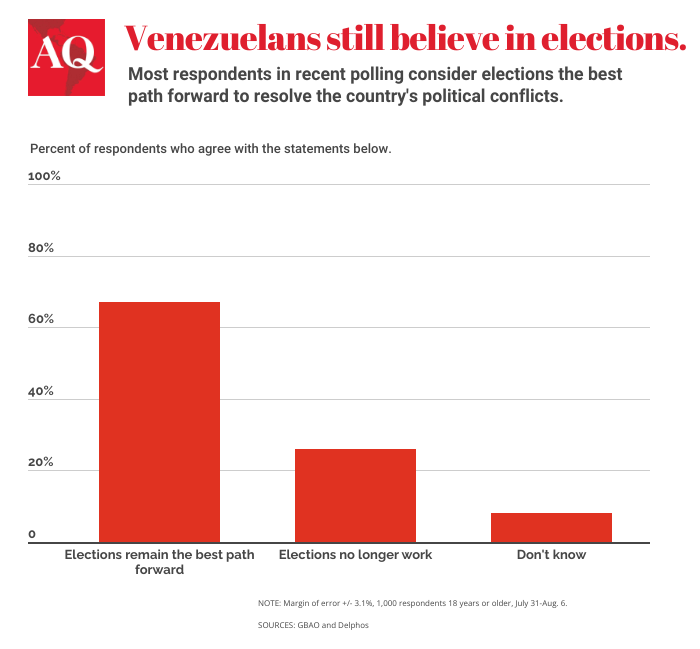

All this activity resonates with Venezuelans from different parts of the political spectrum who continue to see the election, with all its flaws, as the best option to start solving the protracted political crisis, its profound economic fallout, and, more importantly, the severe humanitarian emergency affecting the neediest. According to a recent poll by GBAO, a Washington, D.C. polling firm, and Delphos, a Venezuelan company, two-thirds of Venezuelans agree that elections remain the best way to put political conflict behind; only one-fourth think it is time to consider other options.

A critical test comes on October 22 when about a dozen candidates will stand in the primary to choose the opposition standard bearer for next year’s general election. Longtime opposition figure Maria Corina Machado will likely win handily, polls show. A socially tolerant free marketer, Machado has been uncompromising in her frontal criticisms of the regime since the days when the late President Hugo Chavez was consolidating his power and has stood apart from the rest of the opposition.

Divide and conquer

As Machado soared in the polls, she was banned from running for president on June 30. The move complicated the already complex negotiations the Biden Administration has been conducting with the regime in Qatar and raises a fundamental question:What happens if Machado wins the primary?

Will she be allowed to run next year? If not, will she step aside and support an alternative opposition candidate? Can the United States meaningfully lift sanctions in exchange for steps by the Maduro regime to improve electoral conditions if Machado is barred from running and does not support an alternative opposition candidate?

Machado believes that if she wins the primary, she can leverage domestic and international pressure and negotiate with the regime to allow her to run. The regime, she notes, should not be allowed to choose its opponent, and that condition should be a red line for the international community. Biden administration officials agree.

Machado will face countervailing pressure, however, from other opposition leaders. Personal rivalries and policy differences combine to make her a divisive figure in certain opposition circles. Some in the opposition are already calling on her and another candidate the regime barred from running to drop out of the race. Suppose Machado is not allowed to run next year: In that case, most of the opposition will likely run an alternative candidate, compelling her either to back that contender or urge her supporters to boycott the election.

If Machado opts to encourage abstention, her supporters will face a choice between loyalty to her and belief in democratic principles on the one hand, and pragmatism and commitment to elections, even substandard ones, on the other. For the regime, this has the makings of an optimal scenario—a fractured opposition with lowered turnout that could allow Maduro to win a plurality.

The will of the people

Fearing this outcome and cognizant of polls that show a unified opposition would defeat Maduro, some opposition figures make two arguments in favor of Machado’s deferring to another candidate. They point to a state-level election in 2021 when the regime disqualified a series of opposition candidates, only to lose to another. They also cite the example of Ricardo Lagos, a Chilean socialist who deferred to the more moderate Patricio Aylwin to represent the opposition in an election to choose the first successor to the dictator Augusto Pinochet, in 1989. Effectively transitioning from Maduro, the argument goes, requires a conciliatory figure who can reassure the outgoing regime and its base.

Whatever the merits of these arguments, there is a difference between the stakes of a small state-level election and the representation of a country, and the case for an alternative to Machado was more compelling when she was one of many competitive candidates rather than the dominant figure polls suggest she is now.

Either way, Machado is poised to emerge as the leader of the opposition and its international symbol and spokesperson. The degree of opposition unity in next year’s election will hinge on her, as will any momentous breakthroughs in U.S.-Venezuela talks.

The elections, however, have a momentum of their own regardless of diplomatic discussions in Qatar or the proclivities of individual candidates. Experts on Venezuela have long assumed that a successful election and potential transition are contingent on an agreement between the Maduro regime and the United States. Perhaps—but with or without a deal, the Venezuelan opposition and voters are committed to taking advantage of the electoral process, whatever the odds of success.

Feierstein is a senior advisor at the U.S. Institute of Peace, the Albright Stonebridge Group and GBAO.