BRASILIA — Over the last four years, I spoke to dozens of multinational companies and pension funds that wanted to invest more in Brazil—but felt they couldn’t, because of President Jair Bolsonaro and his policies toward the Amazon. Even in segments not explicitly tied to the environment, like commercial real estate or restaurant chains, there was a feeling that boards of directors and customers alike would not tolerate greater exposure to a country where both the rainforest and democracy itself were under threat.

The very brand of Brazil became toxic, especially in Europe. It didn’t help that Bolsonaro’s ascent to power coincided with the rise of ESG (environmental, social and governance) goals as a new standard for corporate performance. Many took the plunge anyway; Brazil received some $50 billion of foreign direct investment in 2021, making it the world’s sixth-biggest recipient. But that was still only about half the level the country often saw in the early 2010s. I know of one case where a $900 million investment was tabled because a CEO concluded the reputational risk wasn’t worth it. “Huge yield, but a huge headache,” he told me. “It’s not for us.”

With Bolsonaro now on his way out, Brazil has a golden opportunity to recapture many investments—if they don’t mess it up. Call it the “normality dividend.” President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has said many of the right things, traveling to the COP climate summit in Egypt for his first post-election trip abroad, declaring “Brazil is back” and making clear that sustainable growth will be a pillar of his government. But he has also sent contradictory signals on his future economic policy, sending billions of dollars rushing out of Brazil once again, at least until things become more clear. The continued refusal of Bolsonaro and his supporters to fully accept the October 30 election result has also contributed to a feeling that politics will remain unsettled for some time. During several days spent between Brasilia and São Paulo, I heard one recurring theme: The election is over, but uncertainty remains as high as ever.

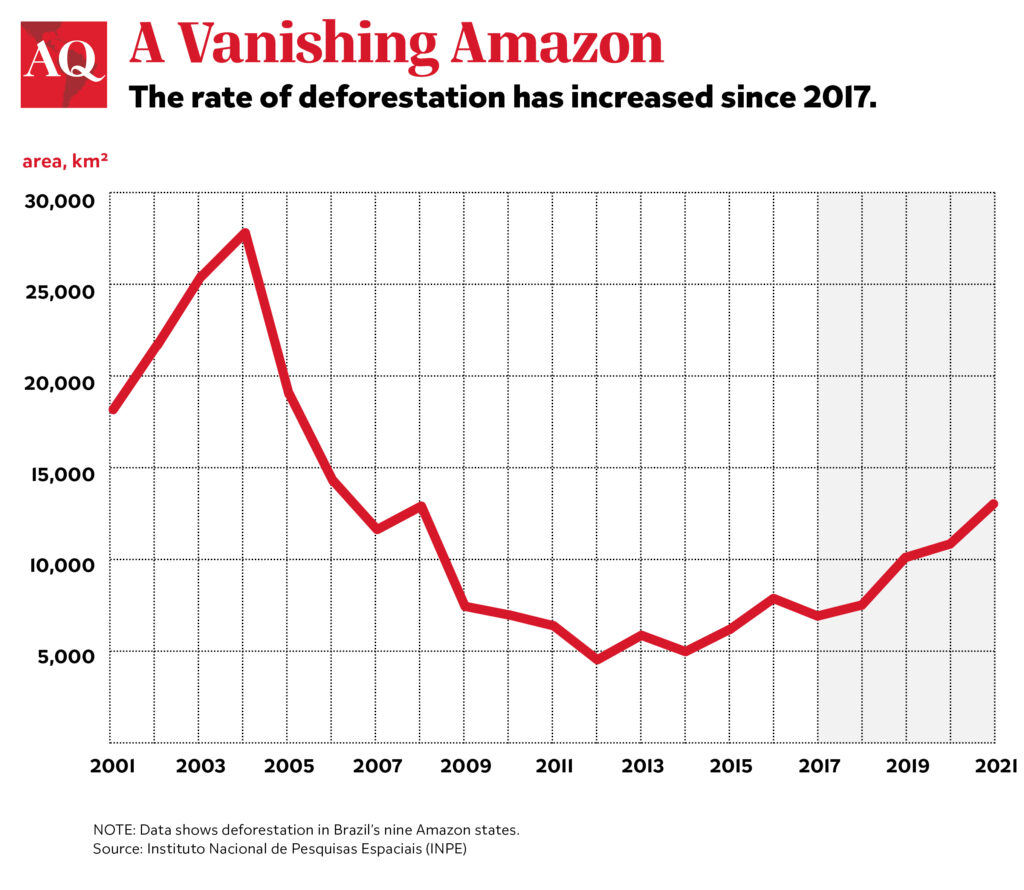

There are reasons to believe Brazil will indeed seize the moment. Under Lula’s first presidency from 2003-10, the rate of deforestation fell by about 75%. I’ve always thought of that as the clearest proof that Lula was more than just a passive beneficiary of good timing from the commodities boom of the 2000s; the turnaround in the Amazon required financial resources, technical expertise, a good team (Marina Silva, and many others) and the ability to build political consensus around conservation in affected areas. Under Bolsonaro, deforestation has soared back to its highest level since 2008. And since the election, the number of fires in the Amazon has grown an additional 1,200% compared to last year, according to satellite data, as farmers and loggers race to slash and burn as much as they can before the new sheriff—well, the old one—comes to town.

In theory, it wouldn’t take much for Lula to reverse the trend. He seems set to reappoint Marina Silva to a key position, and make environmental stewardship the axis of Brazil’s relationship with the rest of the world. Since Lula was last in office, technological advances have opened up new opportunities for the sustainable production of products like fish, cocoa and guava in a global market worth more than $175 billion annually, but in which the Brazilian Amazon has only a 0.17% share, according to a study published in AQ and elsewhere last year. Many in Brazil’s business community supported Lula in this election precisely because they believe that becoming a “green superpower,” and treating the rainforest as a valuable asset, is the key to unlocking a whole new era of economic growth over the next 20 years.

But no one thinks that will be easy. In a foreboding twist, some of Bolsonaro’s strongest support in the October election came from areas that have seen the most deforestation—suggesting many residents quite like the slash-and-burn model, believing (falsely, considering the region’s history) that deforestation will bring jobs and broad prosperity. They will not look kindly upon the return of environmental inspectors and other federal officials, especially under a president they will see as illegitimate. Some believe that talk of “green jobs” and targeted social spending could win skeptics over. But that will require resources, and Brazil already faces a fiscal challenge next year and beyond.

Which brings us back to the uncertainty surrounding Lula’s economic policy. Brazil will have a tight budget in 2023, in part because Bolsonaro spent billions on subsidies and additional welfare payouts this year in a vain effort at reelection. Everyone in the business community knew Lula would seek additional spending to continue a welfare program that pays poorer Brazilians about $110 a month at a time of undeniable social need. But so far Lula has shown signs of asking for much more than expected, and lashed out at “speculators” and others who dare to suggest that’s unwise. “Why do people need to suffer for us to keep the so-called fiscal responsibility?” he said on November 10—comments which, predictably, triggered a further selloff in financial markets.

Why does this matter so much? Well, it was fiscal mismanagement, along with corruption scandals and the end of the commodities boom, that wrecked the Brazilian economy in the mid-2010s under Lula’s hand-picked successor, Dilma Rousseff. The average Brazilian remains 10% poorer than a decade ago in large part because of that crisis. Lula has insisted his government will be “responsible.” But he has also appointed several key faces from the Rousseff-era debacle to his transition team, and shown a hesitancy to genuinely share power with the moderates who supported his presidential bid in the name of saving democracy.

It is not wrong, or prejudiced against the left, as some have suggested, for foreign and Brazilian investors to sell assets or sit on the sidelines for now. It is simply to wonder whether Lula and his party learned the right economic, political and ethical lessons from last decade’s collapse, or whether they will be content to put the old band back together and proceed mostly as before. The jury is still out, and will remain so until Lula names his Cabinet—and likely beyond.

The smart money on Avenida Faria Lima, Brazil’s Wall Street, continues to bet that Lula’s third term will be neither a disaster nor a raging success—that he and his team will be pragmatic enough to produce a new era of solid, if unspectacular, economic growth. The question is whether that will be enough to govern a polarized country where Bolsonaro’s die-hard supporters remain in the streets, where millions are suffering from hunger and unemployment, and where Brazil’s Congress, media and courts will be ready to pounce at the first sign of renewed corruption or other irregularities. One thing is clear: Moving past the Bolsonaro era and healing the Amazon are preconditions for many investments to return, but they are not enough on their own. Normality may yet prove elusive for Brazil.