This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Guatemala.

When Gilberto Kassab founded his party, the PSD, in 2011, he uttered a phrase that has become famous in Brazilian politics: The PSD would be “neither right-wing, nor left-wing, nor centrist.”

This made many Brazilians laugh, for he was describing a long tradition, of which the PSD is only the latest and strongest version—that of parties that work, if not quite with anyone, certainly with a wide range of political groups.

As of March, three ministers in President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s center-left government were from the PSD, the Social Democratic Party. But Kassab himself was holding a job in the administration of a key right-wing opposition figure: São Paulo Governor Tarcísio de Freitas, an ally of former President Jair Bolsonaro. In the 2010s, the PSD was part both of Dilma Rousseff’s cabinet and of the president who deposed her, Michel Temer.

When talking about Kassab, analysts sometimes bring up the phrase “Someone who takes their socks off without removing their shoes,” a Brazilian saying used to describe savvy politicians. But Kassab is not an empty vessel. Despite lending support to left and right, he generally represents center-right and right-wing positions, particularly on economic issues. He became successful by navigating the crucial role that negotiation and accommodation play in Brazilian political culture. “Many politicians in Brazil’s history have that characteristic, including President Lula,” says Maria do Socorro Sousa Braga, professor at Universidade Federal de São Carlos.

“A party must have a power project, otherwise there’s no reason for it to exist. A power project and a country project,” Kassab told AQ in a recent interview.

It’s a formula that has produced results. Kassab is seen today as one of the most important behind-the-scenes political operators in Brazil. The PSD is now the biggest party in Brazil, as measured by the number of people living under the party’s mayors (Lula’s Workers’ Party, or PT, is only seventh by this metric). It has the most seats in Brazil’s Senate and the fifth-most in the chamber of deputies.

If the PSD’s politics are amorphous, they may reflect those of the nation at large. For all the talk of Brazil’s polarization between Lula and Bolsonaro in recent years, a poll run by the Senate in 2024 showed that 40% of participants said they didn’t identify with any political group—right, left or center.

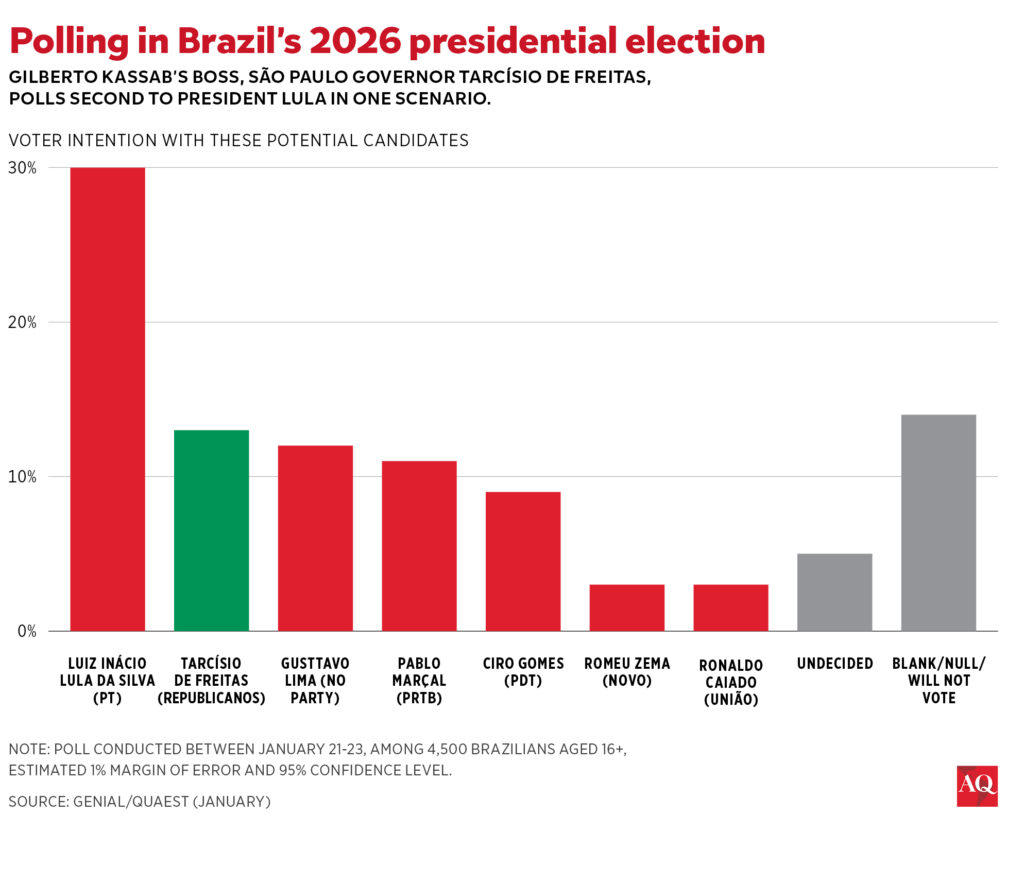

Indeed, Kassab’s story highlights Brazil’s political reality: A country divided between 29 parties, a Congress that has gained increased control over the budget, and a series of relatively weak presidents. Kassab and the PSD play a key role in guaranteeing governability, and also serve as a kind of barometer at a time when Brazil’s political winds appear to be shifting again. Lula’s popularity has fallen this year, Bolsonaro has been disqualified from running again in 2026, and the business world’s preferred candidate happens to be Kassab’s boss: Freitas, the São Paulo governor.

How he got there

Kassab was a young man, still in college (he studied both engineering and economics at the prestigious Universidade de São Paulo, USP), when his uncle first noticed his political abilities. He got along with everyone and was clever. The uncle introduced Kassab to Guilherme Afif Domingos, a businessman and politician with connections in São Paulo’s public and private sectors.

It was the mid-1980s and Brazil was just beginning to have democratic elections again, after 20 years of dictatorship. Kassab worked on Afif’s campaign for Congress and rose through the ranks of São Paulo’s center right/right, becoming first a municipal council member, then a state legislator, a federal deputy and later the city’s mayor (2006-13).

In the middle of his tenure he launched the PSD and promised his party would support the administration of Rousseff, with whom he in theory had little in common. But Kassab and his allies were tired of being shut out of government, and Rousseff’s PT was in need of more reliable partners in Congress. “The PSD was almost commissioned by her,” said Marcus Melo, a professor at the Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Former colleagues even joked that PSD stood for Partido Só da Dilma, or Only Dilma’s Party.

In 2015 Kassab joined Rousseff’s administration as a minister for cities. But as her government started to weaken, the PSD began to defect. Kassab left the administration just days before she was impeached by Congress. In typically genteel fashion, but also taking some political risk given Rousseff’s unpopularity, he wrote her a public letter, saying he was convinced of her personal integrity and democratic commitment. “I say goodbye with the certainty that Brazil will emerge stronger and more united from this process.” Months later, he was named a cabinet member of the administration of Michel Temer, her vice president, whose party played a key role in her impeachment (MDB).

When confronted with the fact that he and his party have played a role in every administration since its founding, he says there was one exception: Bolsonaro’s (2018-22). Indeed, he was not a cabinet member, and the party remained officially independent. However, many prominent PSD members were Bolsonaro supporters and repeatedly voted with the administration—while others didn’t, in typical PSD big-tent style. Kassab recently met with Bolsonaro, who, according to Brazilian media, asked for his support for a piece of legislation that would give amnesty to those involved in the attack on Brazil’s government buildings on January 8, 2023.

Although Kassab prefers the label “independent,” the PSD is often associated with the centrão, the so-called big center, a group of parties with often shifting allegiances who generally pursue pork-barrel spending for their constituencies. But Kassab and the PSD are a little more clearly defined than the centrão. He has brought into his ranks other politicians associated with the center-right, such as Rio de Janeiro’s Mayor Eduardo Paes. “We advocate for a lean state, where everything that the private sector can do better than the state, it should do, which opens up resources for the state to invest in public policies for security, health and education. That is the path to a more prosperous country,” he told AQ.

Some say Kassab’s style is reminiscent of how politics used to be conducted in Brazil, in a pre-social media and polarization age. He wakes up early, travels a lot, and attends all kinds of political events. Allies say he is cordial and attentive. Key aides help him keep track of what funds allied mayors have asked for, whether or not they were delivered, and whether or not the mayor in question showed their gratitude.

What he means for the future

Kassab’s PSD has fine-tuned his strategy to a new political era—one in which the legislative branch has much more power than it used to. Since 2013, Congress has taken advantage of a series of unpopular presidents and approved a roster of constitutional reforms that have given it increasing control over Brazil’s budget.

The proportion of discretionary government spending allocated to Congress jumped from 3.95% in 2014 to 28.8% in 2020, settling at around 20% in 2024. The funds now controlled by lawmakers often flow directly to local governments, highlighting the importance of the PSD’s dominance in municipalities. That power means Kassab’s party will likely elect even more candidates in next year’s legislative elections, increasing his influence over whoever wins the executive branch. But Kassab has even bigger ambitions—he wants his PSD to reach the presidency.

As the political class moves toward the next election, Kassab’s steps are being closely watched. He is known for aligning with likely winners. Earlier this year, he stirred controversy by stating that if the election were held today, President Lula would lose. Lula dismissed the comment, saying, “When I saw the story about Kassab, I started laughing. I looked at the calendar and saw that the election will only be in two years.” Kassab later clarified: “It is still too early to say anything about the election. He can still turn the tide. He is strong.”

However, Kassab does have a favorite: Tarcísio de Freitas, who would represent a right-wing coalition. If Freitas runs, the PSD will back him, Kassab told AQ. In that case, Kassab would like to run for governor of São Paulo, Brazil’s richest state.

Publicly, both claim that Freitas will not put his name in the hat for president, but Brazilian media reports that the topic has been under discussion, especially as President Lula’s approval ratings have declined. “It’s obvious that Tarcísio is going to be president. I’ll bet you anything,” Kassab said. “I think it will be in 2030. Could it be 2026? Maybe, but it’s difficult. 2026 has already started.”

If Freitas seeks re-election as governor instead, Kassab wants to be his vice-governor. That way, he could later run for governor from the more advantageous position of already holding an executive post—making victory far easier.

At the same time, Brazilian media reported in mid-March that Kassab was negotiating with the Lula administration a possible role for the PSD in a PT 2026 ticket.

PSD stands for the Social Democratic Party, not because it espouses social democratic views, but because Kassab wanted to reignite a mid-20th century PSD, which had in its ranks a particularly beloved former president, Juscelino Kubitschek (1956-61). It was extinguished in 1965 by the military dictatorship that began the prior year. Kassab tried to frame his party as a revival of this politically sophisticated PSD. He even planned to create a think tank that would be named after JK, although the former president’s family didn’t allow him to. In some ways the PSD is seen as a party that tries to position itself as more enlightened than the centrão. Kassab says his goal is to keep it “in power, with good posts, in Brazilian politics for two or three hundred years.” Time will tell how he and the party continue to evolve.