BUENOS AIRES — A massive blackout had just plunged 40% of the country into darkness and President Alberto Fernández had just delivered the final state of the union address of his term, but on the morning of March 2, the only news story on Argentina’s major TV news networks was footage from the city of Rosario, where gunmen had fired overnight into a supermarket owned by the family of soccer superstar Lionel Messi.

“Messi, we’re waiting for you,” read the threatening message left behind by the assailants, which continued with a reference to the mayor of Rosario, Pablo Javkin. “Javkin is a narco, he won’t protect you.”

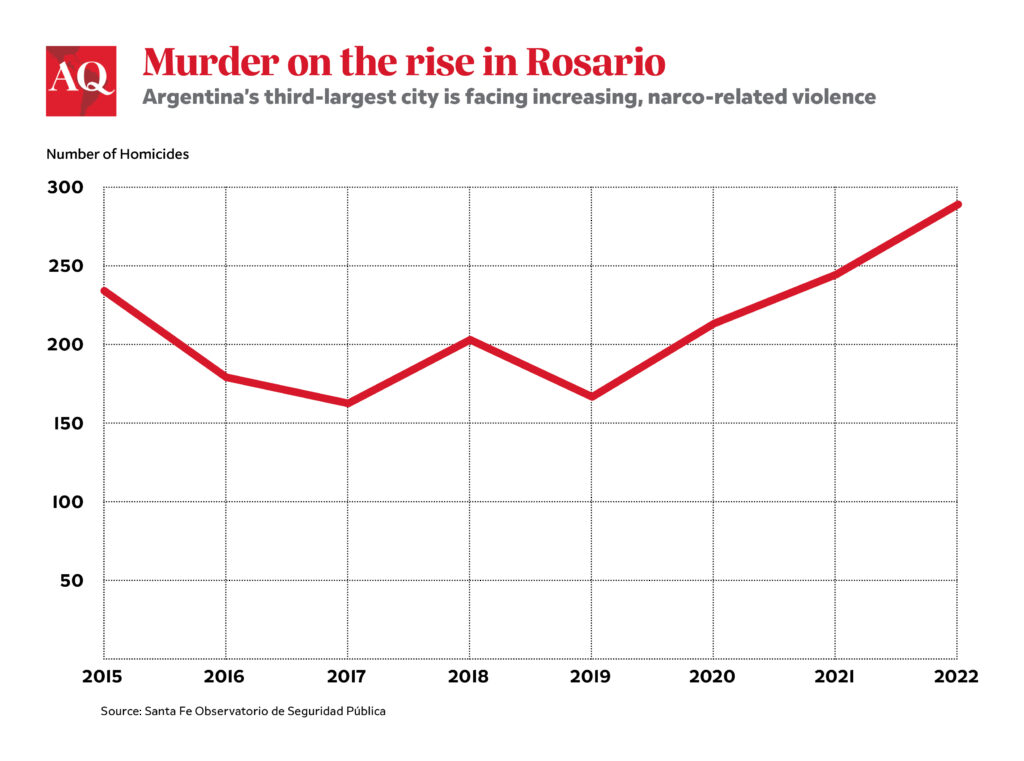

As Security Minister Aníbal Fernández admitted, the disquieting attack was evidence that “the narcos have won” in the largest city in Argentina’s Santa Fe province. The following Sunday brought more sad news: reports of the death of an 11-year-old boy in the city, when gunmen attacked a birthday party.

As inflation nears 100% and a drought in the countryside saps Argentina’s already scarce foreign currency reserves, one would expect the country’s economic woes to be the single dominant topic of conversation in an election year. And especially so, considering that Argentina is an island of relative safety in the region.

While property crimes have been elevated for some time—with a third of Argentines reporting being recent victims—the overall murder rate, at 5.3 per 100,000, stands as one of the lowest in Latin America. (The U.S.’s murder rate is 6.5.) As of 2021, robbery was up by 10% year over year but homicide was down 14%.

Yet amid a worsening situation in Rosario, located at a crossroads in the continent’s drug trade, and in the wake of several high-profile killings in the generally wealthy and safe capital, something surprising has happened: Security issues have come to rival economic ones as a topic of political discussion, with wide potential implications for the upcoming elections.

Last year, a survey undertaken by the University of Buenos Aires’s psychology department showed that 80% felt that the security situation had worsened over the past six months. Among supporters of the opposition—though not of the governing coalition—concerns about security were raised with almost the same frequency (84%) as concerns about inflation (87%). Another poll, by the firm Opinaia, shows security tied with corruption for second place to inflation as of February, but ahead of poverty—which wasn’t the case a year and a half ago.

“There is a widening gap between real crime indicators and fear of crime,” said Marcelo Bergman, professor of sociology and criminology at the Universidad Tres de Febrero. “But people really believe that crime is out of control, that it’s unsafe to walk in the street, and it’s true because thefts are increasing.”

In Buenos Aires, massive billboards on highways feature the face of Patricia Bullrich, president of the PRO party who has declared her intent to run for the presidency as part of the opposition Juntos por el Cambio (JxC) coalition—and the slogan: Hay que poner orden (“Order must be imposed”).

Responding to the events in Rosario, Bullrich emphasized her published plan to use the military to help address the situation in the city. It’s a controversial move in Argentina, where twentieth-century history has ingrained a distrust of the armed forces’ involvement in domestic affairs.

“We have to use all the tools of the state to defeat [the narcos], including the armed forces,” she wrote on Twitter.

Bullrich is doggedly staking out a hardline position on security, which she hopes will give her an edge against her rival within the opposition primary, Buenos Aires Mayor Horacio Rodríguez Larreta. She recently criticized Rodríguez Larreta, who is running on a more centrist platform, for being slow to get Taser stun guns into the hands of the capital’s police force, after a policewoman was shot and killed in the Buenos Aires metro system in February.

“[The issue of security] could have more impact in the Juntos por el Cambio primary than in the general election, because in the primary there are two strongly defined lanes, one tougher and the other more mild,” said Diego Gorgal, professor and senior security expert.

By emphasizing her tough stance on crime, the former security minister might also be seeking to draw support away from Javier Milei, a libertarian federal deputy and another potential presidential contender among the opposition. Milei has attracted attention with his fierce denunciations of what he calls Argentina’s “political caste”—but his libertarian beliefs make a law-and-order position more difficult to take.

Could the opposition’s emphasis on security—along with nonstop crime coverage in national news outlets that tend to have more sympathy for the opposition—be intended to draw attention away from the opposition’s often less popular package of economic adjustment measures?

“Milei is posing an electoral threat from the right, so tilting right [on security] is a smart move to stop the bleeding,” said Andrés Malamud, senior fellow at the University of Lisbon’s Institute of Social Sciences. “It is difficult to face him in the economic arena, but much easier on all others.”

And Bullrich’s hard line on security is already having consequences beyond the opposition primary. On March 7, President Fernández announced he was planning to send 1,400 federal agents to Rosario, with the armed forces set to help with logistical measures. The move could be read as an attempt by the government to take some of the wind out of Bullrich’s sails—at the price of lending credibility to her plans.

“To begin to solve our problems, exceptional measures [need to be] taken against a catastrophic situation,” argued Fede Angelini, vice-president of Bullrich’s PRO party, and a federal deputy from Santa Fe province. Asked which was more important, inflation or security, Angelini told AQ they were “on the same level—it doesn’t help you much to have money if they kill you.”

Security, a regionwide concern

Argentina isn’t alone in the region in being a traditionally safe country dealing with new worries about security. In Ecuador, President Guillermo Lasso’s approval has sunk as previously peaceful Ecuador has seen the rapid growth of organized crime and violence in recent years. And in Chile, polling shows that crime is voters’ top concern, amid a growing perception of insecurity in the capital, Santiago, and in the north.

Meanwhile, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s drastic measures against gangs, throwing tens of thousands into prison with scarce access to counsel, has drawn condemnation from human rights groups—but admiration from many politicians across the region. So far, no major Argentine politicians are among those to hail Bukele’s strategy.

How is the security issue playing with everyday Argentines? A woman working at a corner store in Munro, a lower-middle-class area just north of the city limits of Buenos Aires, called the security situation in her neighborhood, further west, a “disaster” and said her brother’s house had been ransacked by thieves despite being located just a few meters from a police station. But other residents of the area reported that crime wasn’t a top concern and said their vote would be decided by other factors.

Gabriela Oliveira, who works in elder care and lives in Florencio Varela, in the south of the Buenos Aires metropolitan area, reported a marked deterioration in safety in recent years.

“Politicians concern themselves with [things like] road maintenance … but regarding security there’s terrible abandonment,” she told AQ, citing not drug activity but rather a lack of employment opportunity for youth as a principal cause, and citing security concerns as the issue that would most influence her vote later in the year. “It’s the most important point.”

Regarding the possibility of an expanded role for the armed forces in security, she added, “I’m in agreement with Patricia Bullrich.”