BUENOS AIRES – Next June 20, Flag Day in Argentina, is a patriotic date. It could also mark a pivotal moment for the country’s efforts to replicate the U.S. fracking boom—on the eve of a presidential election.

The Alberto Fernández government is working against the clock to complete construction of a 356-mile-long gas pipeline before winter hits Argentina, and demand for gas—and imports—spikes. Vaca Muerta, in Neuquén province, is the world’s second-largest shale gas deposit, and the fourth biggest in shale oil. With the duct in place, its massive resources could be made readily available to large urban populations.

Completing the Néstor Kirchner pipeline has become a race against time for Finance Minister Sergio Massa, who set June 20 as the date to deliver the first part of the project. With most polls suggesting a complex outlook for the ruling Peronists, financial stability could play a major role in the run-up to the August primaries and the vote in October. The economy is in dire straits, with less than $5 billion in net reserves, and 56,700 tubes of steel could make all the difference.

Although the finance minister has repeatedly played down intentions to seek the presidency, he is widely considered a likely contestant for the top job from the ruling Frente de Todos coalition. His electoral chances, however, are tied to the fate of the economy, which nearly 75% of Argentines regard as in bad shape and deteriorating further. In his six-month tenure as finance chief, Massa has pledged to deliver several things. First was to bring monthly inflation down to 3% by April. But the latest 6% figure for January makes reaching that goal unlikely. The pipeline, in turn, could be decisive for a second goal: keeping the Argentine peso stable.

Ever since the war in Ukraine began, the government has been talking up its potential to supply global energy markets. However, it has yet to achieve energy self-sufficiency on its own turf. Last year, Argentina footed a $4.3-billion-dollar bill in gas imports, despite having the world’s second-largest shale gas reservoir. “One of the great adversities that our economy suffered last year was the impact of the war on the price of (liquefied natural gas) shipments,” Massa said recently. “With the pipeline, that will no longer be necessary. This is the last year that Argentina will need to import (gas).”

A “Dead Cow” comes to life

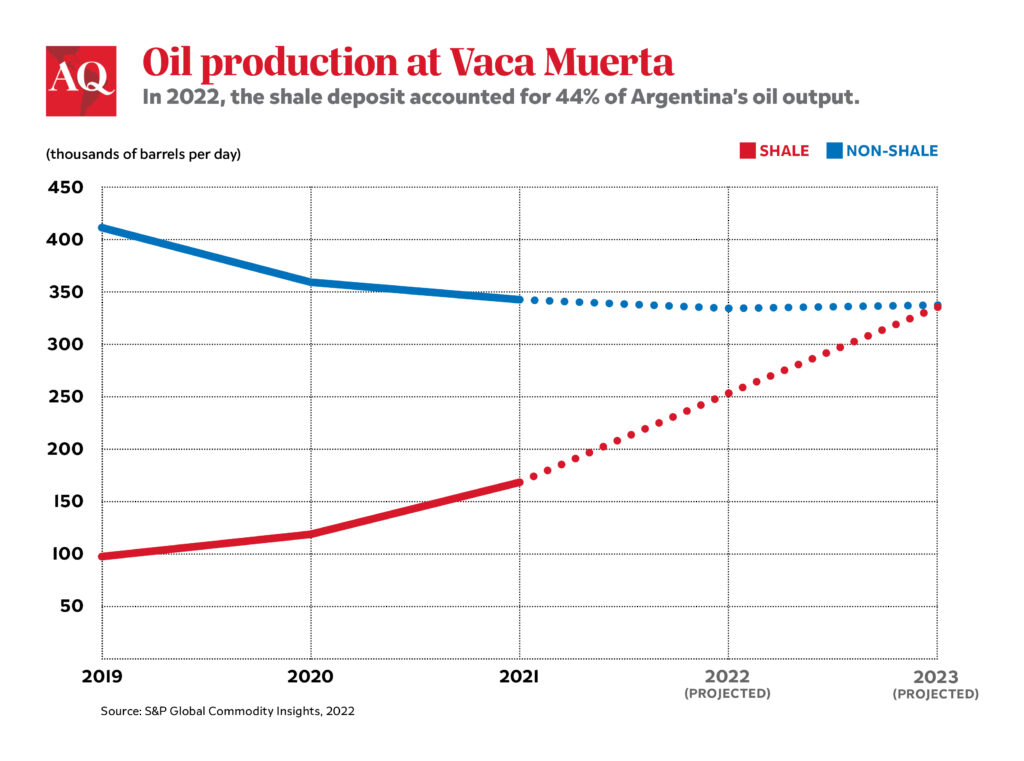

After significant investments in recent years, Vaca Muerta production is picking up speed at an impressive rate, growing at double-digits every year. Until 2018, the country produced little to no oil and gas from unconventional sources, according to official data. Fast forward to today, when shale resources alone now account for 44% (oil) and 39% (gas) of Argentina’s total production.

Vaca Muerta covers an area roughly twice the size of Connecticut. Only a small acreage is being exploited, yet in the coming quarters, the formation is bound to take the lead as the country’s most relevant area for oil and gas. Official data shows that in 2022 Argentina produced 250,000 barrels a day of oil from unconventional sources, and close to 73 million cubic meters of gas, up 47.7% and 23.2%, respectively, over 2021.

At a time when bans on Russia are reshaping energy supply chains, Argentina’s potential in Vaca Muerta could make the country “a rival” to world-class players in LNG such as Australia and Qatar, S&P Global Commodity Insights reported last year. German chancellor Olaf Scholz’s visit to Buenos Aires in January included discussions around lithium and gas, two of the most strategic assets Argentina has to offer. Germany’s dependence on Russian imports triggered an energy crisis following the Kremlin’s invasion. Scholz emphasized coordinating energy policy and supply. “This applies to LNG,” he said.

The pipeline

Infrastructure is the key element if Argentina is to take full advantage of the ramp-up in production. Named after deceased former president Néstor Kirchner, the Fernández-Kirchner government wants the pipeline to become a milestone of the administration. President Fernández has repeatedly celebrated the project advances on social media with a clear electoral tone. The government is projecting the pipeline will help save $2.4 billion in imports this year alone, more than half the central bank’s stock of net foreign reserves. With just $4.3 billion in net international reserves—according to private estimates—every dollar counts. The country is already under an agreement with the IMF to accumulate foreign reserves, rather than spend them.

The first section, promised for Flag Day, connects Vaca Muerta to Buenos Aires province. A second trench would allow for exports to Brazil. Argentina “could start exporting gas to Brazil as of September,” Massa said in an interview with The Financial Times. Delays, however, have been reported in local media, suggesting that the June 20 deadline could be at risk. Timing is not trivial. Failing to make good on the promise to deliver before winter hits would lead to hefty LNG expenses once again in 2023.

Still, the government commits to its deadline. “The work has all its sections active and is at full speed,” a spokesman from IEASA, the state-run company leading the construction, said. “The date is June 20.”

Vaca Muerta has the potential to not only save some money in the short term, but also to overturn Argentina’s long cycle of stagnation and decay. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates 14.4 billion oil barrels and 38 trillion cubic feet of gas lie underground. This could allow Argentina to incorporate $20 to $30 billion every year in gas sales alone, the government estimates. But that windfall will only come once the pipeline is ready, and running. The question that will be answered on June 20 is who will reap the political benefits of its completion.

—

Feliba is a financial reporter covering Latin America. He has written for the Washington Post, the New York Times and S&P Global Market Intelligence, among other publications.