This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s ports

“There are different categories of fancy Mexican,” says one character in Nicolás Medina Mora’s debut novel, América del Norte.

These include fresas (“harmless, except for their accents, which are known to cause aneurysms,”) pipopes, mirreyes, progres (“fresas who read Open Veins of Latin America”) and juniors (“the nepo babies of someone in the Cabinet”).

In this mock taxonomy, the novel’s protagonist, Sebastián Arteaga y Salazar, is a junior. His father, one of Mexico’s most powerful men, is a Supreme Court judge. Raised in a climate of overwhelming, even suffocating privilege—trailed everywhere by bodyguards since the age of 10—Sebastián, who has literary ambitions, decides to become an American writer instead.

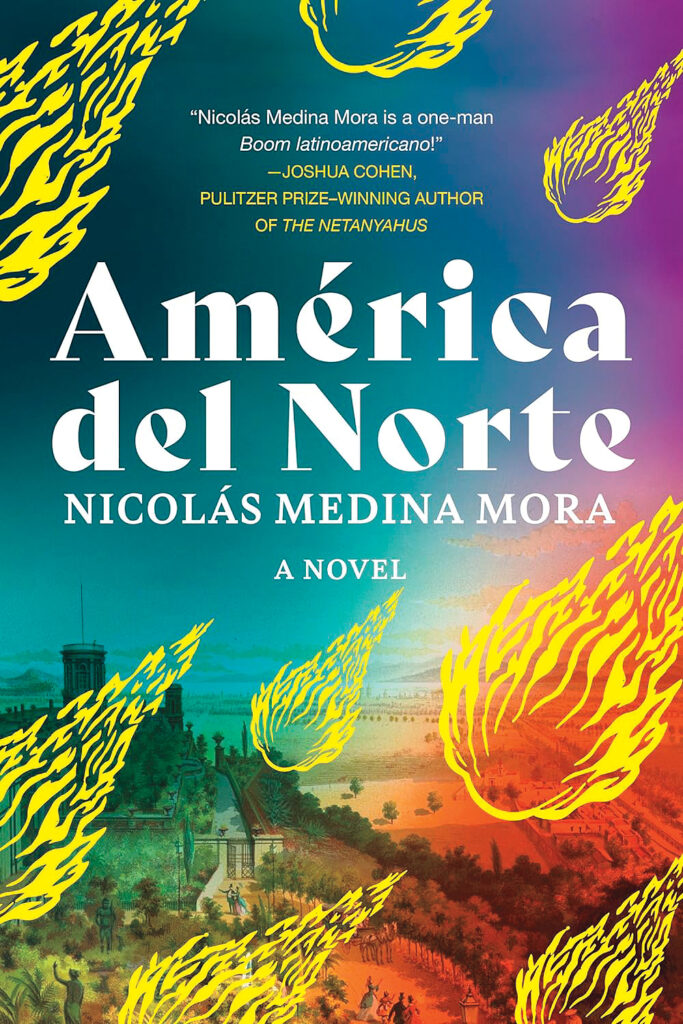

América del Norte

Nicolás Medina Mora

Soho

Hardcover

480 pages

At first everything goes according to plan: an Ivy League education, stints at the trendiest Brooklyn media outlets, admission to the best creative writing program. But then it all goes wrong. Donald Trump cuts the supply of U.S. visas. His mother falls ill with cancer. The rise of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) brings his father’s political downfall. Finally, Sebastián’s romance with a U.S. woman falters, blotting out his last hope for a green card.

The novel’s author has a familiar last name. His father, Eduardo Medina Mora, played a major role in overseeing Mexico’s drug war. After being appointed to the Supreme Court by Enrique Peña Nieto, he resigned in 2019 after being investigated for alleged irregular payments.

A powerful father is not the only similarity between author and protagonist: Medina Mora went to Yale and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, worked at Buzzfeed News and writes for n+1. In the novel, he uses his fictional alter ego’s failed Americanization to paint a double portrait of two interlinked North American elites.

In previous generations Mexico’s elite had looked to France, disdaining the U.S. as uncivilized. But then, as one character puts it, NAFTA “made rich Mexicans want to become Americans—and not just any kind of American … the sort of people they met on their Easter trips to Disneyworld.”

Sebastián wants to become American too, only a more sophisticated kind. But he is irritated at the way he is encouraged to exoticize his own background in his writing, by people who don’t realize how privileged his upbringing was. In his failed bid for a visa, Sebastián discovers the limits of U.S.–Mexico exchange. Goods and services may be able to move freely across the border, but he can’t.

Sebastián comes to resent the “hateful” and racist U.S., but his social critique is muddled with personal disappointment. In the Mexican context, Sebastián has scorn for the heroes-and-villains view of politics he attributes to AMLO, but his U.S.-tinged progressivism often takes a similarly moralistic form. Sebastián sees that “the politics I’d acquired in America” should lead him to share AMLO’s antipathy for Mexico’s political elite, including his dad—but he takes the opposite tack, calling his father’s resignation under duress from the Supreme Court a “soft constitutional coup” by AMLO.

Medina Mora’s lively intelligence and humor compensates for some of his narrator’s less agreeable tendencies. Hopping between the U.S. Midwest and Mexico City, the novel interweaves reflections on Mexican history and Hegel with childhood flashbacks and long nights in dive bars. América del Norte has a formidable goal: to define the contradictions of contemporary North America and its elites. But where those contradictions overcome the author’s own powers of observation, the book breaks down into its constituent parts: a literary CV in the American context, and the diary of a junior in the Mexican one.