The president who almost wasn’t

Guatemala’s Bernardo Arévalo was nearly prevented from taking office. Now, can his drive to reform the country succeed?

BY JOSÉ ENRIQUE ARRIOJA | APRIL 22, 2025

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Guatemala | Leer en español

GUATEMALA CITY — When you enter Bernardo Arévalo’s office today, everything seems almost normal.

There is no sign of the upheaval that nearly stopped him from assuming the presidency after he won 61% of the vote in Guatemala’s 2023 election. No hint of the court battles, the opposition’s efforts to destroy his political party, the street protests in his favor, nor the repeated desperate interventions by the international community that many credit with letting him take office—and, perhaps, helping keep him alive.

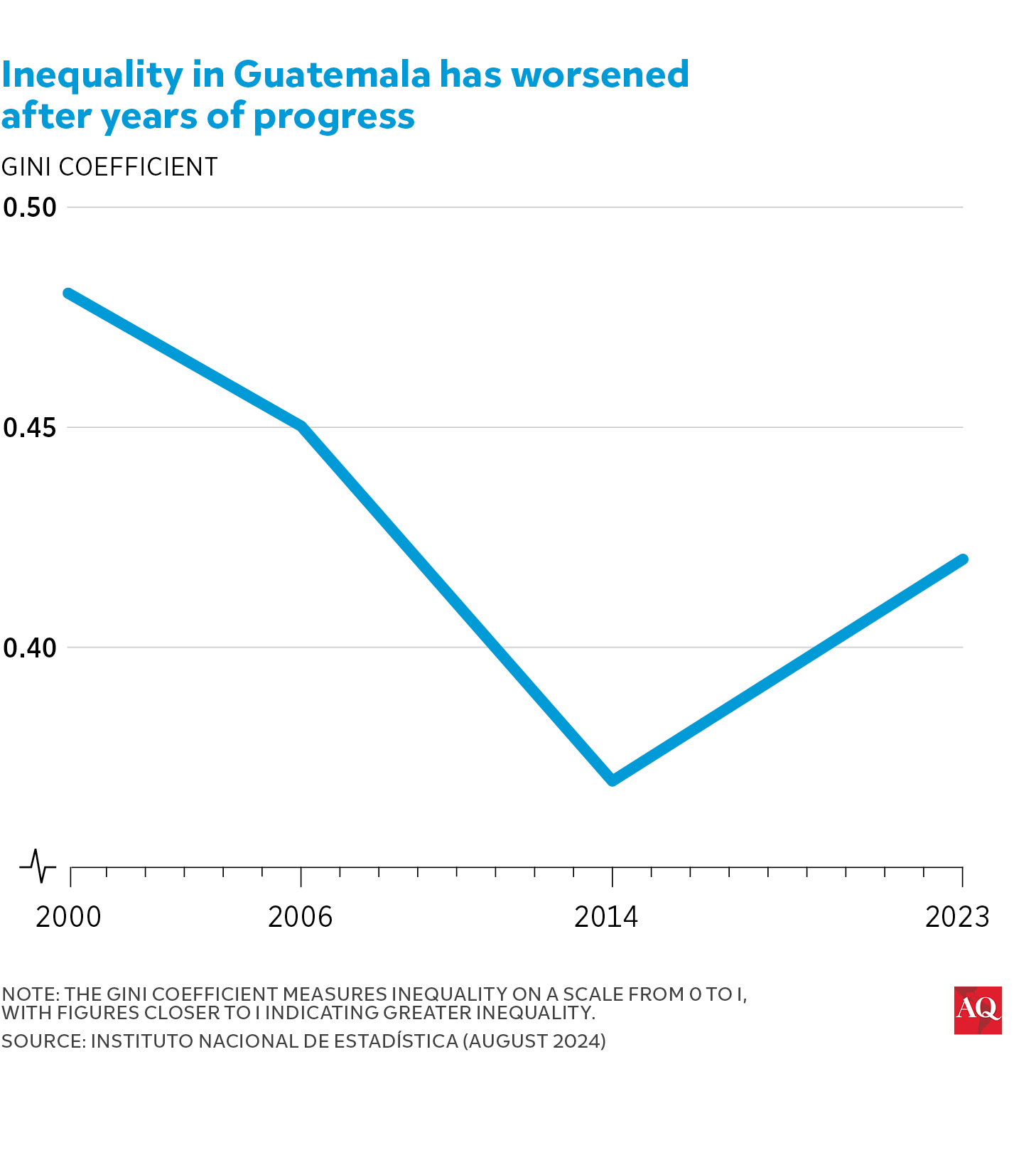

There is, instead, only a calm, goateed 66-year-old who sounds exactly like the trained sociologist and philosopher he is—analyzing the numerous challenges of one of Latin America’s most unequal nations with a kind of scholarly remove, urging patience even as some of his supporters grow frustrated with the slow pace of change.

“We are creating a space, an institutional rescue. And for us, the institutional rescue is the sine qua non that (will) allow us to generate development later,” Arévalo told AQ in an interview.

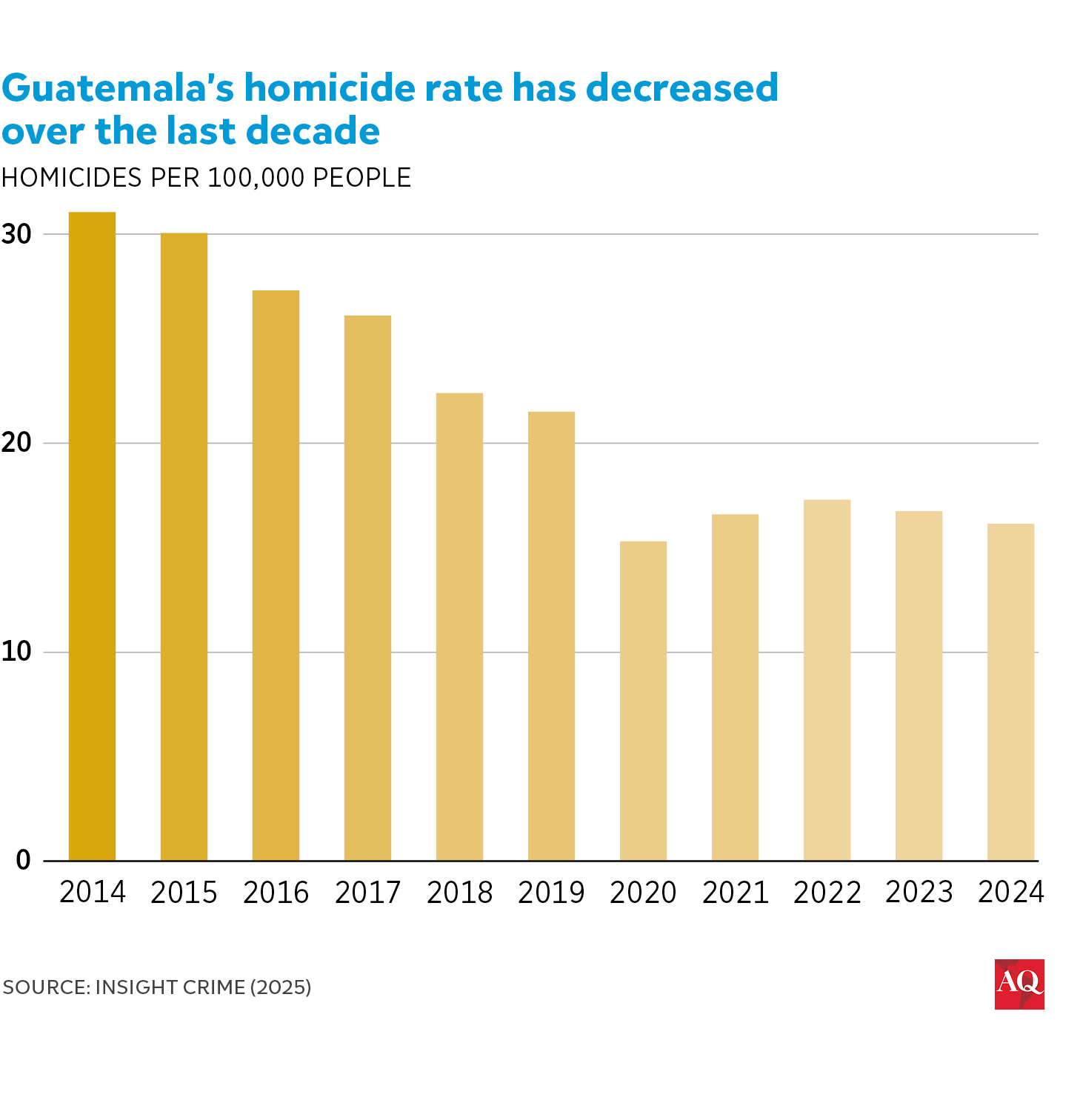

Since he took office in January 2024, in a ceremony delayed several hours as the opposition mounted one last dramatic attempt to stop him, several things have gone right. Guatemala’s economy is expected to grow 4% this year, and Arévalo’s center-left government has passed some important reforms, including an antitrust law and a new legal framework for building infrastructure, one of the country’s most pressing challenges. Arévalo has forged a constructive relationship with parts of the private sector. Guatemala’s homicide rate, among the world’s highest just a decade ago, has continued its decline—and now stands at an all-time low, even lower than that of Costa Rica.

On the diplomatic front, Arévalo has survived the departure of his most critical international ally, Joe Biden, and surprised some observers by building a seemingly positive relationship with the Donald Trump administration, cooperating closely on key issues like immigration and drug interdiction while avoiding—at least so far—any of the turbulence that has hit peers like Mexico, Colombia and Panama.

Indeed, many celebrate the fact Arévalo is still here at all. The powerful segment of the Guatemalan establishment that resisted his inauguration, seeing Arévalo as an existential threat to their grip on political and economic power, has certainly not given up. Since taking office, Arévalo has faced 13 impeachment petitions and six attempts to remove his immunity from prosecution. His biggest rival, Attorney General Consuelo Porras, whom the U.S. has sanctioned for alleged corruption, remains in office and seemingly ready to act upon any hint of weakness or wrongdoing.

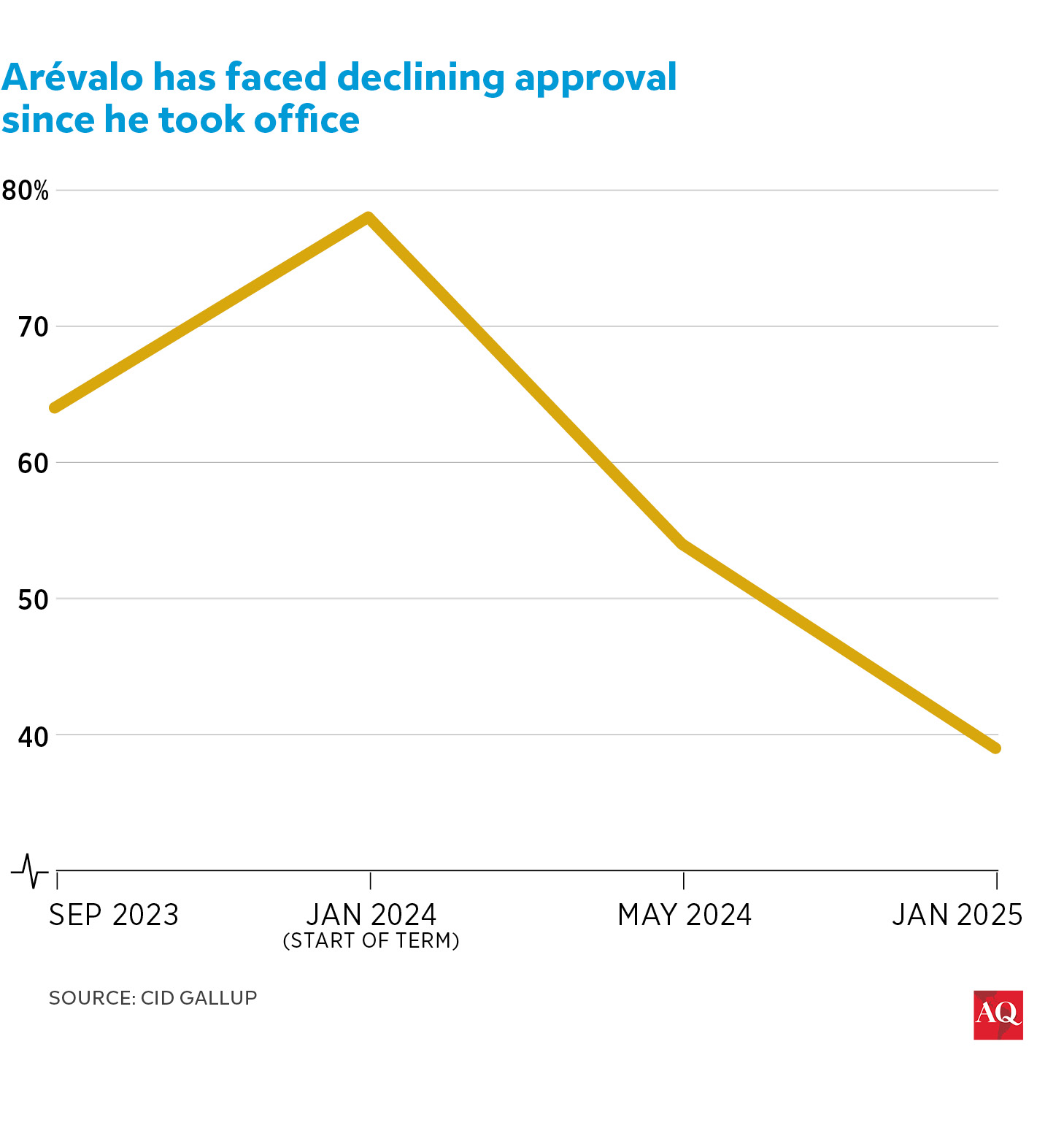

No one believes he’s out of the woods. Arévalo’s popularity has fallen from 78% at the beginning of his term to only 39% in January, according to CID Gallup. Some Guatemalans see him as overly contemplative and not decisive enough. Others are angry he hasn’t yet done more to change the status quo in a country where 56% of the population lives in poverty, child malnutrition is entrenched, and millions have emigrated in recent years in search of a better life, though that exodus has slowed of late.

But even amid this adversity, Arévalo is seemingly taking the long view. In our interview, he referenced the idea of a “democratic spring”—a phrase associated with his father, Juan José Arévalo, the country’s first-ever democratically elected president, who governed from 1945 to 1951 and implemented several reforms including a national minimum wage and social security system. That period of promise ended when his successor, Jacobo Árbenz, was toppled in a 1954 CIA-led coup, ushering in several decades of civil war, authoritarian rule, and—in more recent years—fragile, often flawed democracy.

“We will witness the democratic spring (once again) when we tangibly rescue the institutions from the corrupt actions of the state.”

—President Bernardo Arévalo

“We will witness the democratic spring (once again) when we tangibly rescue the institutions from the corrupt actions of the state and put them to work for what they were created for,” Arévalo told me. Over the course of 40 minutes, he outlined a bold vision for progress on social spending, education, infrastructure, security, and democratic reform—which, if implemented, would be game-changers for Central America’s most populous nation and largest economy.

(Erick Velásquez/EBLA Digital)

A rocky road to the presidency

Arévalo was born in Uruguay in 1958, a few years after his father was forced into exile. Despite his family’s history, for years, he steered clear of electoral politics and built a name for himself as a career diplomat, serving as vice minister of foreign affairs and ambassador to Spain. He then took several jobs on reconstruction and reconciliation projects, leading initiatives for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and Interpeace, an international organization that focuses on building peace and fostering connections in post-conflict societies.

Arévalo finally entered politics in 2020 as a lawmaker for Semilla, a small party. He ran in the 2023 presidential election as a long-shot candidate, and thus appears to have escaped the scrutiny of Guatemala’s entrenched elites. Three other candidates in that race were disqualified on technical grounds widely seen as political in nature; Arévalo, polling below 3% in most surveys, was allowed to run.

But then Arévalo surprised virtually everyone by getting 12% of the first-round vote, enough to get into a runoff, thanks largely to strong support in Guatemala City and other urban areas. Alarm bells went off right away: Running on an explicitly anti-corruption platform, Arévalo was very obviously not part of the club of politicians that has mostly dominated Guatemalan politics since democracy returned in the 1980s. Before and after the runoff, the Public Ministry went into open confrontation, with courts and opposition legislators engaging in numerous actions that Arévalo described at the time as a “slow-motion coup.” (See the 2023 Election Timeline.)

(Luis Echeverria/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The Biden White House, concerned about another source of instability in Central America and eager to prop up a fragile democracy, spun into action, urging then-President Alejandro Giammatei to guarantee the democratic transition as well as Arévalo’s own security. The U.S. canceled hundreds of visas for politicians and business leaders alleged to be interfering with the transition, and sent a procession of officials to Guatemala City to pressure for the popular vote to be respected. The European Union, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, several other countries, and even the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights supported Arévalo’s cause. Much of Guatemala’s private sector, including institutions such as FUNDESA, CACIF and the Chamber of Commerce, also spoke against efforts to overturn the election.

Today, Arévalo speaks with some relief of the forces arrayed against him: “With changes in the courts and the political landscape, this power is becoming increasingly isolated and is disappearing.”

Nevertheless, the constant clash with the judiciary absorbed much of Arévalo’s first year in office. More than a dozen everyday citizens I talked to in this city recognized he has been navigating against the current. At the same time, most complained that the government has been slow to implement the expected changes and to show results in what Arévalo has called a “semi-destroyed” country.

“In politics, perception is everything,” Raquel Zelaya, president of local think tank ASIES, told me. In a country with a pronounced authoritarian tradition, Arévalo is perceived as “a negotiator, a person of dialogue, who bridges gaps,” but lacking the capability to impose his will and set a course. “That doesn’t fit the idea of power and command that we suffered for years.” Additionally, Arévalo and his newly empowered party show “surprising divisions when they should be fully united. They are confronting many challenges,” she said.

(José Enrique Arrioja/Americas Quarterly)

A fragmented legislative power

One of them has been Congress. Throughout 2024, Arévalo faced a divided Congress, but Semilla’s 23 lawmakers managed to broker consensus with 16 political blocs and the other 137 representatives that conform the chamber. At the end of the period, Congress approved 36 key laws or decrees, including an antitrust law. (Until the passage, Guatemala was the only country in Latin America without such legislation.) Also relevant was the approval of the Priority Road Infrastructure Law, focusing on developing and maintaining the key roads that converge on and surround Guatemala City and connect the nation’s maritime ports and main airport.

“This year, we have an ongoing dialogue with Congress and a clear agenda for the proposals we want to submit,” Arévalo told me with an optimistic tone. A new law for civil aviation is needed to modernize the La Aurora airport, an outdated facility in the heart of the city that serves international and national flights and urgently requires expansion and upgrades. The government’s procurement and acquisitions law is antiquated and distorted after several reforms, requiring a new bill. Civil service and water legislation also need updates, Arévalo said, as does legislation governing maritime ports on both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The government also has two anti-corruption laws in the pipeline, one initiative on technology and a reform for the nation’s criminal code to ensure more substantial jail and financial penalties for those breaking the law.

“It is a challenge for a government to have a minority bloc in Congress,” Arévalo told me, because “its performance depends on the ability to establish alliances necessary for governability.”

Others agreed. Sonia Gutiérrez Raguay, the only self-described Indigenous lawmaker in Congress, admits that the Arévalo’s administration didn’t have “all the allies it needed” last year, complicating the government’s performance during the “democratic crisis” the nation endured. “We want to see the continuation of this government, and our party is in favor of advancing the progress and democracy in our country,” said the lawmaker from the WINAQ-URNG party.

As a political organization, Semilla is contesting three legal actions filed against it that have reduced its members to independent lawmakers in Congress, according to Andrea Reyes, the legislator in charge of the party’s legal defense.

(José Enrique Arrioja/Americas Quarterly)

“We want to see the continuation of this government, and our party is in favor of advancing the progress and democracy in our country.”

—Sonia Gutierrez Raguay, lawmaker from the WINAQ-URNG party

The infrastructure link

For years, Guatemala has tried to become a destination for investment in the textile, construction, and manufacturing sectors. However, an old and decaying infrastructure network, from incomplete roads and bridges to insufficient ports and railroads, has always limited the country’s potential. Indeed, the need for better infrastructure was made tragically clear once again in February when a bus crossing a bridge in Guatemala City collided with several vehicles and plunged into a ravine, killing 53 people. Arévalo decreed three days of mourning.

“Guatemala’s main problem right now is its poor road infrastructure quality,” Elmer Palencia, the congressional leader of the opposition party Valor, told me in his office, citing “high logistics costs that ultimately translate into high living costs” for both regular citizens and companies.

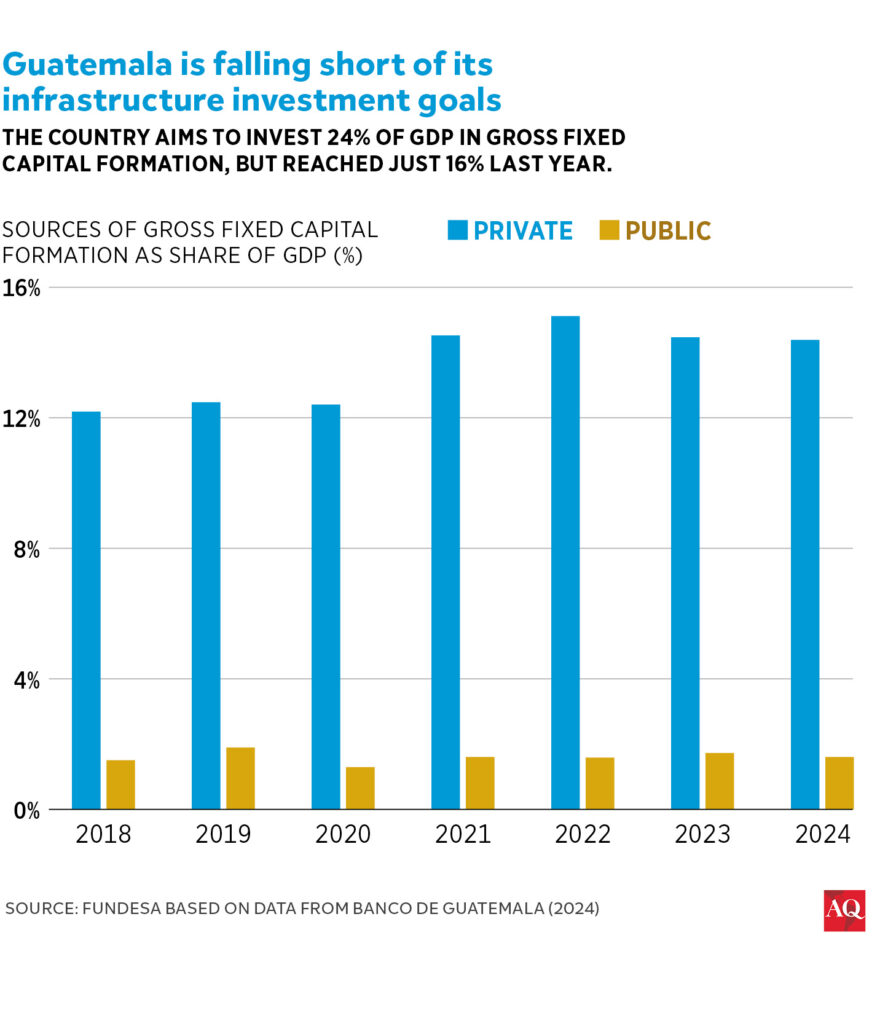

Guatemala is known for its lack of government investment. In 2023, excluding Haiti, the country ranked last in public expenditure in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to data compiled by OECD and ECLAC. The public infrastructure investment rate is also the region’s lowest, and with 19,000 kilometers of roads, it has little more than one meter of road per capita, the lowest in the Western Hemisphere.

Aware of the challenge, Congress passed the Priority Road Infrastructure Law in November to repair, maintain, and expand more than 1,600 kilometers of critical roads. The legislation, which Palencia authored, will enable the government to invest as much as $5 billion per year in public works. “The government now has the tools they need. Now they have to execute,” he added.

As the system is set up now, the government cannot build large-scale projects that surpass $120 million, according to Juan Carlos Zapata, the director of the Foundation for the Development of Guatemala (FUNDESA), who applauded the approval of the infrastructure law as a “big achievement” for Arévalo and Congress. However, he said the country still needs additional legislation, such as reforming the current law for public-private alliances and the one that regulates the port system. “With those tools (laws), I’d say that projects worth $250 million or $300 million would be structured, which will be transformative.”

The execution issue

The problem with completing infrastructure projects goes beyond anything on paper. “It’s a challenging task,” Miguel Ángel Díaz Bobadilla, the minister of Communications and Infrastructure, told me at his office near the international airport. For years, the ministry “has not only been the booty, but the petty cash of many administrations,” leaving behind uncompleted or poorly maintained works. “Over the last 40 years, this ministry has been used to embezzle the public treasury,” he added.

A sign of the ministry’s challenges is its high turnover: Díaz Bobadilla is the fourth such minister under Arévalo. But ambitions are big. Arévalo wants to connect Guatemala’s most isolated rural areas with a plan called Rutas para el Desarrollo. “We have identified that the country’s poorest areas are those with the worst infrastructure,” he said. A second plan, named Conecta, will recover most of the national road system “which has been abandoned and neglected for a long time,” Arévalo added.

The government envisions the expansion of Puerto Quetzal (Pacific Ocean) and Santo Tómas de Castilla (Caribbean Sea). In the initial stage, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will design and execute the expansion of Puerto Quetzal. The administration also plans to rebuild the national railway system to connect the previously mentioned ports, creating a terrestrial interoceanic corridor that could be an alternative to the Panama Canal. A second railroad line would connect traffic from El Salvador to Mexico. For the nation’s capital, the government plans to build an above-ground metro and expand the La Aurora airport, a project open to international companies.

(Erick Velásquez/EBLA Digital)

Díaz Bobadilla admits that the government will need to accelerate its execution this year, as 2024 was a “lost year” in infrastructure due to political pressure from the government’s adversaries, he said. “In Guatemala, the corruption is Venice: It has many channels to flow,” he added.

Making progress will require considerable national and foreign investment. Guatemala No Se Detiene, a government-private sector partnership focused on detecting key areas for national development, has put together a portfolio of $8.7 billion in infrastructure projects needed to modernize the country. For the government, the clock is ticking, as Guatemala’s population is expected to rise from its current 18 million to 24 million by 2040.

Climate change is another source of urgency. Guatemala regularly ranks in the top 10 countries most impacted by climate change, as major storms are becoming more frequent and dry seasons longer, affecting agriculture and especially communities with poor connectivity to main roads. This is a key driver of migration from rural areas already beset by high levels of land inequality, poverty, and food insecurity. Better infrastructure adapted to this new reality could mitigate future pain.

Semilla’s 2023 governing platform calls for “urgent” investment in a range of infrastructure initiatives, but for most of these projects, Arévalo will not be cutting the red ribbon. “We are going to start processes and works that future governments will inaugurate. We decided that we needed to put this ship to the sea so it can start navigating,” he told me.

Security as a development hurdle

Security has been a brighter topic. New strategies and better cooperation with the U.S. have proven to be an effective combination. In 2009, the homicide rate was 45.6 per 100,000, but it sank to a record low of 16.1 last year.

To consolidate progress, more resources are needed, David Boteo, the Director of the National Civil Police, told me after speaking at an event at the National Palace. The institution under his watch operates with 41,265 officers nationwide, including 7,602 women, but “we need another 13,000 officers to get 20 officers in each station in the country, which is the minimum that we should have.” Nowadays, each police station has 10 to 15 police officers, Boteo added.

In early March, seven people were killed and another seven injured in two shootouts near the capital. Arévalo is implementing what the government calls a “democratic security program” to tackle as many as 22 gangs operating in connection with cartels in Colombia, Mexico, and El Salvador.

Last year, Guatemala seized a record of more than 18 tons of cocaine and sizable quantities of other narcotics, leveraging the “good communication, coordination and trust of several U.S. agencies,” Werner Ovalle, the vice minister of anti-narcotics, told me. In addition, the government captured 24 criminals facing charges in the U.S. and arrested more than 1,300 individuals on drug trafficking charges.

As elsewhere in Latin America, some Guatemalans yearn for a tougher approach akin to that of President Nayib Bukele in El Salvador. But Ovalle said in Guatemala, “our security model is somewhat different; there are different political and institutional conditions … We are committed to succeeding, so Guatemala would be a country to invest in and become a reference” in public security.

Key international relations

Expectations were high when Trump’s Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, visited Guatemala on February 5, seeking Arévalo’s support on receiving deported Guatemalans and stepping up the fight against organized crime and drug trafficking.

No one quite knew what would happen. Some among the Guatemalan establishment hostile to Arévalo had forged deep ties with the first Trump administration, and Arévalo’s close relationship with the Biden administration was also a potential liability. But the visit appeared to go well. In a press conference, Rubio offered clear support for Arévalo. “I’d like to commend you for your commitment to defending the institutions of a republic, and we will continue to work together with you so that you can achieve what you wish to achieve along that road.”

It turns out the two men had a previously established bond from years ago when Arévalo was a lawmaker for Semilla and Rubio was still a Republican senator. “We discovered (the common ground) as we were talking about the importance of history in understanding the times that we live in,” Arévalo said with a smile, adding that Rubio expressed “his support for the democratic process in our country.”

“Our relationship with the U.S. has been very good since the transition process,” Arévalo said. During Rubio’s visit, Arévalo agreed to increase by 40% the number of flights of deportees with Guatemalans and citizens of other nationalities, from the average of seven to eight flights per week from the U.S. Arévalo also announced the formation of a new border security force that will patrol Guatemala’s borders with El Salvador and Honduras.

(Johan Ordonez/AFP via Getty Images)

The president also mentioned “good relations” with Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum. “We have had working meetings discussing our borders, and we’ve been discussing transforming the region into a development zone.”

“We are also maintaining good relations with Europe and other countries, and we hope that, in addition to good relations, this will translate into an influx of investment, which, in the end, is what we know can make a difference,” Arévalo told me.

Aiming for investment grade

As Central America’s largest economy, measured by population and economic activity, Guatemala has experienced remarkably stable growth in recent years. On average, GDP expanded 3.2% between 2014 and 2023, above the Latin America and the Caribbean average, and probably grew 3.7% last year. The central bank is projecting a 4% economic expansion this year, the highest rate since 2022.

The positive performance led Fitch Ratings to raise the country’s outlook from “stable” to “positive” in early February, citing “expectations of continued solid growth momentum and stability.” It also highlighted Guatemala’s governance challenges as a “key rating constraint.”

The government is working to address those limitations as it looks to obtain an investment grade for its sovereign credit before Arévalo’s term ends in January 2028. “It is one of our main objectives and will be one of the legacies of President Arévalo’s government,” Finance Minister Jonathan Menkos told me in his office. Only seven Latin American and Caribbean countries enjoy investment grade; in July of last year, Paraguay became the most recent addition to the group.

Those aspirations will face a test soon. The Finance Ministry plans to issue as much as $3 billion in international bonds this year, possibly selling bonds denominated in quetzals, the national currency, for the first time. “It’s an analysis we’re still doing. We want to know how much, in what amount, and if there’s interest from different stakeholders,” Menkos said.

(Félix Acajabon/Guatemala’s Finance Ministry)

The country has a solid record to bank on. Guatemala’s sovereign bonds are already trading as investment grade papers in the so-called secondary market, Luis Lara, the Chief Executive Officer of Banco Industrial, told me. He sees the goal as viable given the country’s public finance health and the implementation of the infrastructure strategy. “If Guatemala had better roads, better ports, better airports, we would grow at a rate of 6% per year,” he said.

Arévalo sparked some controversy when, in December, his administration proposed a 10% increase in the national minimum wage for agricultural and non-agricultural sectors and a 6% rise for maquila and export activities. This decision was popular among the working class, but drew opposition from the Comité de Asociaciones Agrícolas, Comerciales, Industriales y Financieras (CACIF) business association, which argued that the increase threatened the country’s economic and social stability.

When asked if additional minimum wage increases were coming, Menkos didn’t rule out the possibility. “I think there will be a rational, objective, sensible, and forward-looking discussion about the minimum wage” as part of a medium-term policy, he said. At the same time, he rejected the possibility of increasing taxes or proposing a fiscal reform during Arévalo’s government.

Raising the minimum wage is necessary to make progress against Guatemala’s protracted poverty, said Carlos Benitez Verdún, the resident representative of United Nations Development Program in the country. Social programs such as Mano a Mano, similar to Bolsa Familia in Brazil, are set to make a sensible difference. “This is a government that aims for development, that doesn’t just want to put out fires,” Benitez Verdún said.

A new year, a new test

As Arévalo tries to modernize Guatemala and revive its democracy, there is consensus that he needs to show results in his second year in power. “The president has been doing many good little things,” Sonia Castillo, a homemaker who voted for him in 2023, told me one afternoon at Plaza de la Constitución, the square overseeing the Palacio Nacional. “I think he’s been a bit slow, but perhaps he needs to think things through before acting. I want him to help the neediest.”

Unleashing the infrastructure program, overseeing the return of deportees to the country, and following through on his education and agricultural agenda will keep the president busy this year while relevant decisions loom in 2026. Arévalo will appoint a new Attorney General to replace Porras, name the ten magistrates of the powerful Constitutional Court, oversee the election of the nation’s Electoral Tribunal, and name the General Comptroller. All key posts that may enable him to reset the leadership of the judicial branch and the electoral authority, the key branches that opposed him in 2023.

For each institution, the president will receive nominations from special committees comprised of authorities from public and private universities as well as from professional associations, such as the influential lawyers and notary’s bar association, which in February chose a new leadership closely aligned with Arévalo’s party.

The four decisions are critical in setting a new course for the nation. “As a country, we’ll be playing for our democracy next year,” Semilla lawmaker José Carlos Sanabria told me.

It is far too early to predict how Arévalo and his administration will pass on to history, but the evident social disparities call for action. “Given the high levels of inequality, we don’t have a consolidated democracy,” said Zelaya of ASIES, the think tank, citing a reality of “two Guatemalas,” rich and poor. “This year, we have to deliver,” asserted the finance minister Menkos, emphasizing the relevance of this year’s performance. “This year must be the year to execute, when people will see the works,” added Díaz Bobadilla, the communications and infrastructure minister.

As for Arévalo himself, he has a characteristically broad legacy in mind. “I’ll be happy if, as a result of this presidential term, the population reaffirms their commitment to the democratic system,” he said to conclude our conversation. It’s an aspiration that was in doubt two years ago, but seems somewhat more secure today.

—

Introduction images: First and fourth photo by Erick Velásquez/EBLA Digital; second and third photos by José Enrique Arrioja.