SANTIAGO — Fresh off his 2021 primary victory, President Gabriel Boric famously predicted that “if Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it would also be its tomb.” Three years later, his ambition to remake Chile got buried instead.

Now approaching his final year in office, the former student activist often sounds less like Marxist icon Salvador Allende and more like the traditional center-left politicians he once derided. He espouses growing the economic pie, vows “mano dura” against crime, and blasts Venezuela as a dictatorship. Has Boric genuinely moderated his convictions? Or, as his less scripted remarks suggest, is this the tactic of an agile young politician biding his time?

Wherever his soul lies, Boric has been unable to accomplish any of his promised structural reforms of healthcare, education, taxes, and pensions, to name a few. But he might be forging a more durable legacy: from the 2019 protests that propelled his meteoric rise to back-to-back attempts at rewriting the Constitution and the missteps of an administration in search of identity, Boric is unwittingly steering Chile back to the successful moderate politics that preceded him.

“If Boric has moderated, this isn’t about a legacy that he pursued or attempted from the start,” Claudio Alvarado, executive director of the Institute of Studies of Society, a think tank in Santiago, told AQ. “Rather, it’s one of resignation to the strength of the facts.”

Three years into his mandate, Boric’s presidency is dogged by chronic tension within his divided political alliance: the Frente Amplio and the communists on whose shoulders he ascended, and the center-left that, after the constitutional debacle, is carrying him through the real work of governing.

This tension reverberates across issues like security, which polls show Chileans are most worried about. Amid extra policing and tougher crime penalties, for example, his government is starting to make progress. Despite contrary public perceptions, the rate of homicide victims in the first half of 2024 fell by 9.4% year over year. In southern regions, the number of arson attacks disguised as Indigenous resistance has come down too. While center-left allies are urging Boric to stay focused on fighting crime, the Frente Amplio is diverting his attention to niche causes such as euthanasia.

The pending agenda

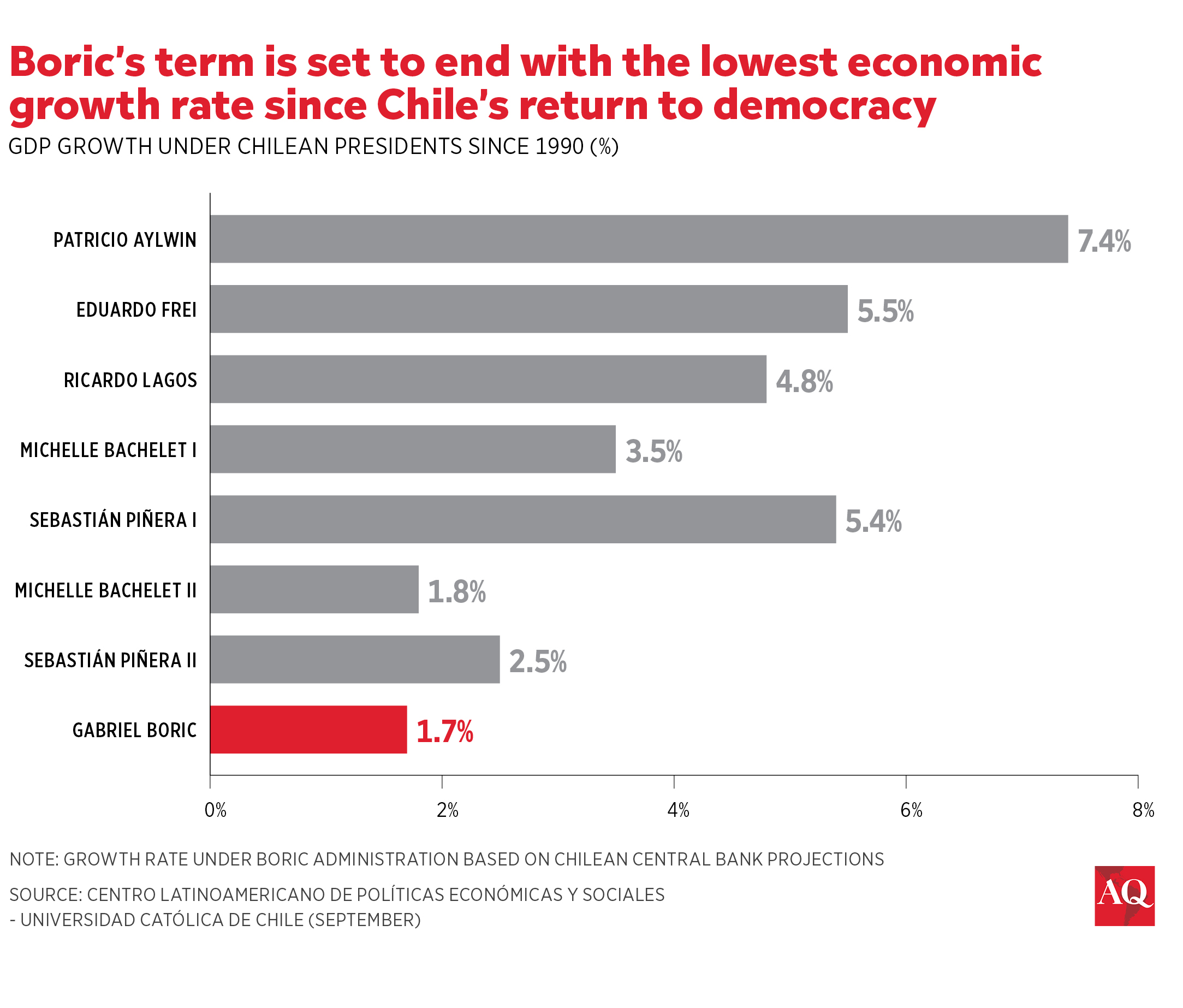

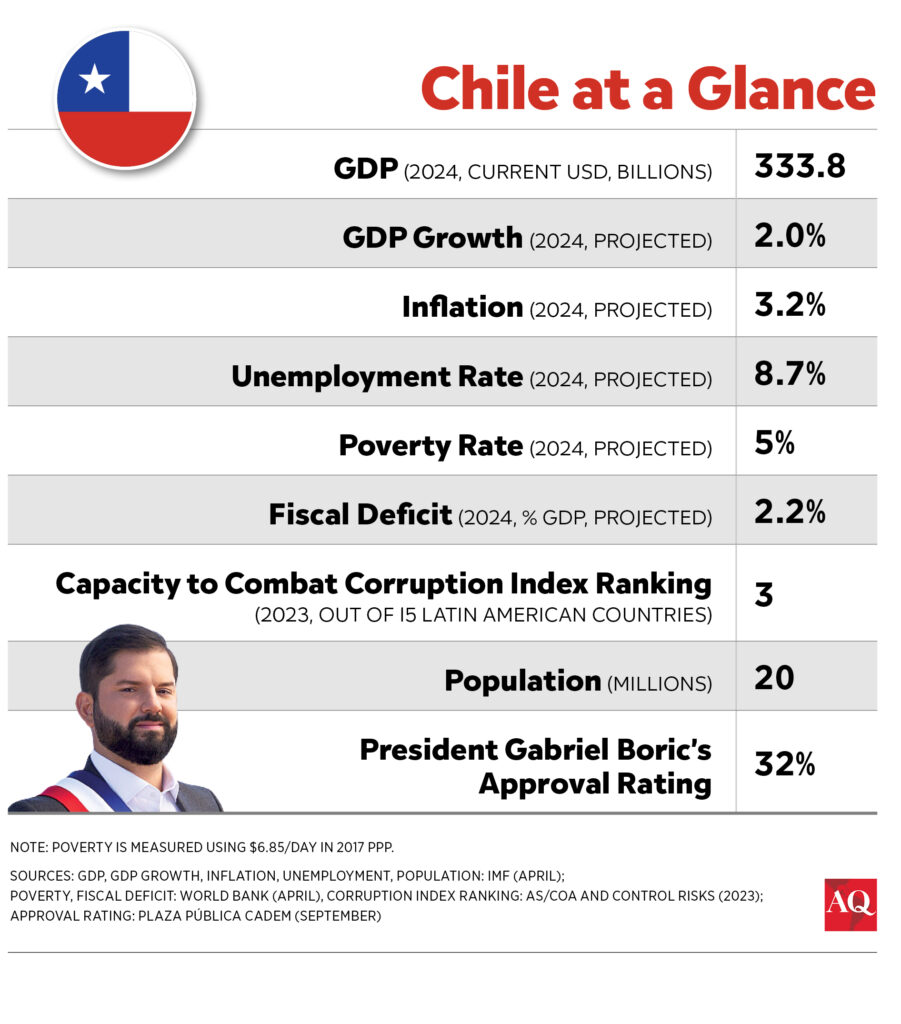

Boric also faces challenges on other key fronts. Chile’s central bank recently cut its long-term annual growth projection to just 1.8% for 2025-2034, putting his presidency on track to register the lowest economic growth since the restoration of democracy.

Permitting lags and a controversial government proposal to borrow from renewable energy margins to subsidize electricity are sullying Chile’s investment climate, the business community says. Significant investments in pivotal sectors like lithium and green hydrogen, disparaged by young progressives as “extractivism,” are stuck. “Boric and his political allies are uncomfortable with any whiff of profit,” entrepreneurs’ chamber president Jorge Welch told AQ.

Boric still has a shot at reforming Chile’s pension system after he abandoned an all-or-nothing campaign against privately managed pension funds. A framework consensus would shore up pensions through an additional 6% in mandatory paycheck withdrawals. But critical details, such as the state’s role, are still undefined. Analysts like Gabriel Ugarte of the Centro de Estudios Públicos argue that a more just and sustainable system that boosts current pensions without robbing future generations will ultimately require an unpopular increase in the retirement age and incentives to create more formal employment.

On education, core problems such as school desertions, poor quality, and violence have taken a backseat to finding a way for Boric to fulfill his pledge to ease the $11 billion debt burden of university students, a key constituency. After a tax reform derailed, his promised forgiveness now resembles a modest, long-term refinancing.

Perhaps most painful for Chileans is the broken public health care system. More than two million patients await treatment by a specialist for basics like eye care and gynecology. Wait times average nearly a year. And the public sector’s management of the wait lists is now under regulatory scrutiny.

One route to tackling Chile’s structural challenges runs through a much-needed reform of the fragmented political system. An administration proposal would raise the electoral threshold for congressional seats and enhance party discipline. “This should only be a first step toward a more substantive reform to bring about congressional majorities as opposed to groups representing small minorities,” constitutional expert Natalia González told AQ. “This can’t just be a tick of the box.”

A revolutionary repents

The radical spark that kindled Boric’s career still glows in extemporaneous remarks that seem designed to appease grassroots supporters disaffected by his political compromises. He told the BBC last year that he “strongly believes” capitalism isn’t the best way to solve society’s problems. More recently, he indulged the class-struggle crowd but trampled on the separation of powers by celebrating the pre-trial detention of an “elite” lawyer in a snowballing white-collar scandal now enveloping the Supreme Court.

For now, Boric’s approval ratings are inching past the 30% that has endured for most of his tenure. The narrative of his political arc, however, remains elusive. At former President Sebastián Piñera’s untimely funeral in February, he waxed repentant.

Boric squandered a historic opportunity to chart a contemporary “Chilean way” to peacefully address social grievances, socialist party elder Carlos Ominami told AQ. Instead, the millennial president might only be remembered for “normalizing” Chile in the aftermath of the estallido and pandemic.

Something else is starting to look normal. Whether out of conviction or expedience, Boric’s coming of age is giving way to a likely presidential contest between moderates rather than the political extremes on the left and the right that his administration helped to discredit. On the center-right, the frontrunner in 2025 is Providencia Mayor Evelyn Matthei, daughter of an Air Force commander who played a role in Chile’s peaceful transition to democracy. Matthei regularly outpolls Boric’s former hard-right presidential rival José Antonio Kast, whose Republicanos party got burned in the constitutional process. Polling behind Matthei is leftist two-time former President Michelle Bachelet, but she seems more likely to try to play kingmaker than vie for the presidential sash again. A more probable candidate is center-left Interior Minister Carolina Tohá. Another contender is the centrist governor of the Santiago metropolitan region, Claudio Orrego.

A race featuring such moderate figures would restore the center-lane politics that brought Chile stability and prosperity, laying a path for gradual reform and bucking the radicalization taking hold elsewhere in Latin America.

This wouldn’t be the legacy Boric intended. If he convincingly embraces it, Chile might remember him well.