Gustavo Petro might be only six weeks into his presidency, but he hasn’t lost any time defining his top priority. “I will work to achieve true and definitive peace. Like no one else, like never before,” he pledged at his August 8 inauguration.

Petro’s agenda, which he has dubbed “total peace,” is nothing if not ambitious. He proposes simultaneous talks with the National Liberal Army (ELN), FARC splinter groups and over two dozen other mafias—all with the goal of ending Colombia’s epidemic of violence once and for all. If the promises sound big, that’s exactly why many Colombians voted for Petro. After his predecessor, Iván Duque, failed to remedy the situation with a more conventional security policy, there was and is appetite for change.

But success is far from guaranteed. For now, Petro can count on a pro-government majority in Congress, seasoned peace negotiators in his cabinet, and an open line to Washington, Havana, and Caracas, each of which may figure in eventual talks. Moreover, while opposition to the 2016 Accord was fierce, Total Peace has received little political pushback. Still, much will depend on whether Petro’s government can get three critical groups on board—all without undercutting the state’s bargaining power in the process.

Support from Strange Bedfellows

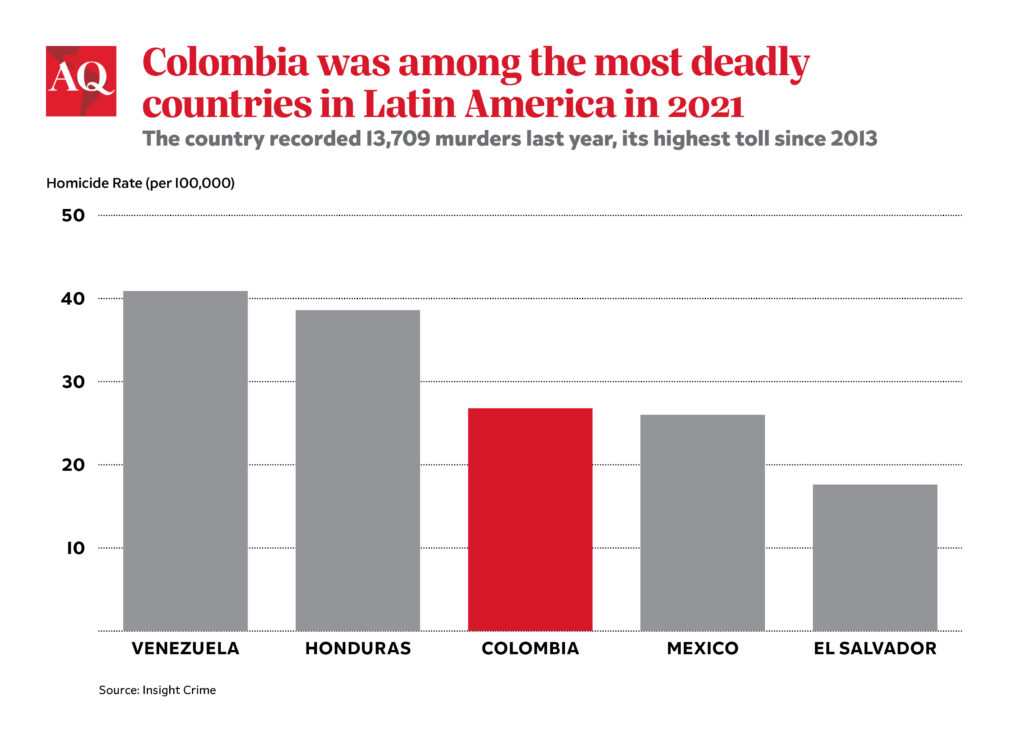

First, Petro needs buy-in from Colombia’s myriad armed groups and criminal organizations. For now, 22 criminal and armed groups have expressed willingness to enter talks—but they have different incentives to accept or reject peace, which could become a hurdle. Moreover, Petro inherited a crumbling security situation from his predecessor: In 2021, Colombia’s homicide rate stood at 26.8 per 100,000, topping even Mexico’s and reversing years of improving security in the run-up to and immediate aftermath of the 2016 Peace Accord.

The ELN, which, at 2,500 fighters, remains Latin America’s largest insurgency, has consistently signaled its interest in engaging in talks with the Petro government. In August, Petro signed a decree lifting the arrest and extradition orders for ELN leaders holed up in Cuba. This week, FARC dissidents, who rebuked the 2016 Peace Accord, also met with the Petro government to explore the possibility of dialogue. And the Clan del Golfo, the fragmented successor to Colombia’s right-wing paramilitaries, declared a unilateral ceasefire on the day of Petro’s inauguration to signal its leaders’ willingness to take part.

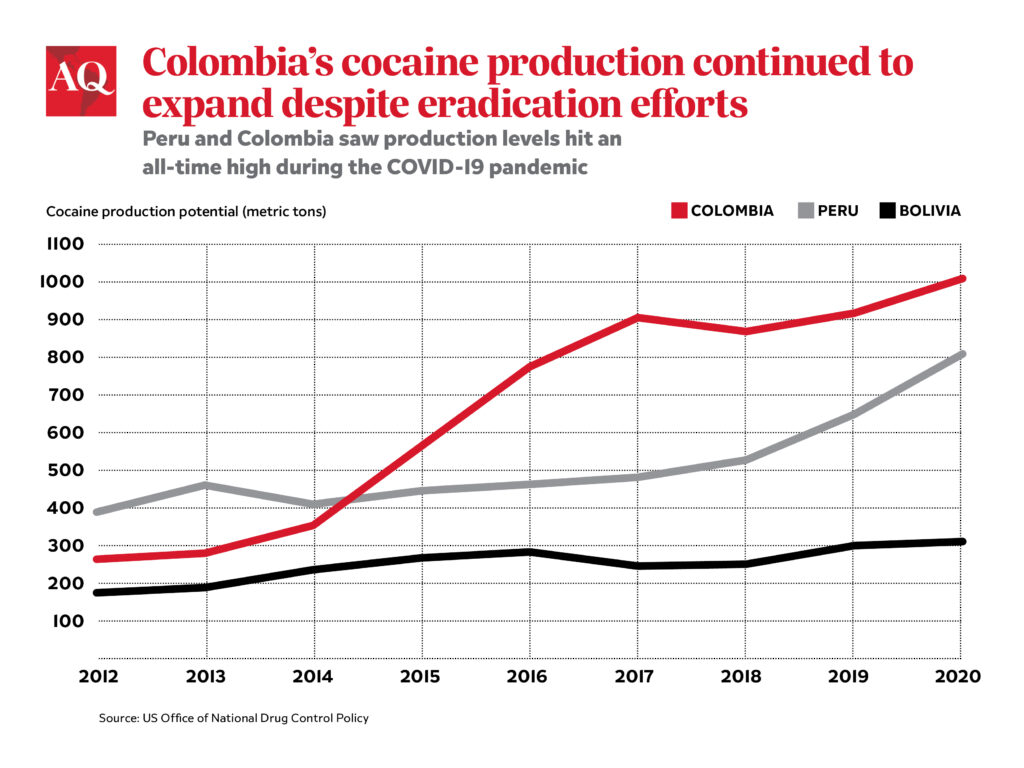

But all three groups—plus dozens of other, smaller mafias—also control lucrative drug trafficking routes and illegal mines and have much to lose from dismantling their criminal fiefdoms. Last year, Colombia’s cocaine exports reached near-record-setting amounts. It’s unclear how criminal groups expect to improve their situation, or safeguard their profits, by participating in talks, but they might be vying to turn their fortunes legal. The Petro government recently announced it has plans to pursue cocaine decriminalization.

If buy-in comes in phases, as it almost certainly will, that could pose its own risks. Still-active mafias could swoop in to take control of territory and illicit trade routes abandoned by groups participating in the talks. That was the story of the swathes of territory vacated by the FARC after 2016. With Mexican cartels growing regionally, a lurking danger is that Colombia’s illicit economies could end up in the hands of new foreign owners with bigger guns.

That’s what makes buy-in from a second group—Colombia’s armed forces and police—even more critical. Few were surprised when the Petro’s relationship with top brass got off to a rocky start. After all, Petro built his career as a critic of state security force’s checkered history of human rights abuses, and appointed Iván Velásquez, famous for investigating links between right-wing paramilitaries and the state, as his defense minister.

But the Petro government has moved quickly and aggressively to change military leadership, purging more than half of Colombia’s generals and police commanders in just six weeks. Observers say those left behind are eager to preserve institutional privilege and reputation and likely to fall in line with Petro’s security policy—provided dissenters among their ranks don’t get the upper hand. Retired generals and officers have already publicly criticized Petro’s plans to negotiate with mafias. Keeping security forces on board will be a must for filling vacuums left behind by criminal groups—but it’s sure to be a balancing act.

Third, although less critical than its domestic pillars, Total Peace also needs international support. After all, Colombia’s criminal and armed groups already rely on trade routes and territorial enclaves that run deep into Venezuelan territory. That gives the Maduro regime unfortunate yet undeniable leverage over Colombia’s security situation. In early September, Petro asked Venezuela to act as guarantor to upcoming talks—a request which Maduro eagerly accepted, drawing sharp criticism from U.S. Senate Republicans and Democrats.

But if Petro aspires to international legitimacy, Total Peace will also require the support of democracies. Chile’s President Gabriel Boric and Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez have both offered support. But it remains uncertain whether democratic governments can ensure any kind of transparent process alongside autocratic Venezuela. While Maduro’s participation could push the ELN, which depends heavily on access to Venezuelan territory, to stay at the negotiating table, it also risks legitimizing a brutal dictatorship likely to have ulterior motives.

Bellwether or Red Flag?

For Petro, Colombia and the region, the stakes couldn’t be higher. After a brief reprieve in violence at the height of the pandemic, organized crime is now resurging with a vengeance, eroding the state and threatening investments in Mexico, turning Brazil’s porous borders into lawless no man’s lands, and roiling once-peaceful countries like Ecuador, Paraguay, and Uruguay. A decade ago, governments across the region opted for head-on confrontation to fight organized crime, but mano dura crackdowns largely failed to deliver the desired results, and now leaders are struggling to find a new way forward.

If Total Peace succeeds, it could provide a blueprint for dozens of other governments across the region and dismantle Colombian criminal groups that have for years spread violence to Colombia’s neighbors, including Peru and Ecuador. But if Petro’s gamble fails, it could spell disaster. Silvana Amaya of Control Risks compared the policy with Colombia’s failed 1999-2002 negotiations with the FARC, which saw the state give the FARC control of the Caguán, a region the size of Switzerland, in a bid to make peace. Instead, the FARC took full advantage of the situation, using the brief reprieve to prepare a siege that would go on to nearly topple the state.

“Today, we’re seeing the formation of mini-Caguáns all over Colombia,” Amaya told AQ. If Colombia’s criminal groups take advantage of upcoming talks to regroup and rearm, the consequences could ripple across Colombia’s borders and give organized crime groups an renewed safe haven. For the Petro government, the current moment presents an unparalleled opportunity and an unparallel challenge. The clock is ticking.