Let’s get right to the point: I do not believe that President Jair Bolsonaro will ever willingly hand over power to his rival in this October’s election, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. If Lula wins, as polls currently suggest he will, there will be an institutional crisis in Brazil in coming months. The only question is what it will look like—and who will ultimately prevail.

Bolsonaro has made his intentions abundantly clear over the past year. Influenced by his belief that Donald Trump won the 2020 election in the United States, and determined to avoid a similar fate (or worse), Bolsonaro has pursued a multi-pronged, if often erratic strategy. He has repeatedly cast doubt on the integrity of Brazil’s electronic voting system, and said he will only accept a result that he deems “auditable”—an impossible bar, since Congress voted last year not to modify the system. He has portrayed Lula not just as an opponent but an illegitimate, “criminal” threat who “can only win via fraud.” Meanwhile, anticipating a confrontation, the one-time Army Captain has deepened his ties to Brazil’s military, appointing retired generals to key posts, including as his running mate. With numerous legal cases pending against him and his family, Bolsonaro has said he sees only three possible futures: “Prison, being killed or victory.” He continues to act as if he genuinely believes that to be true.

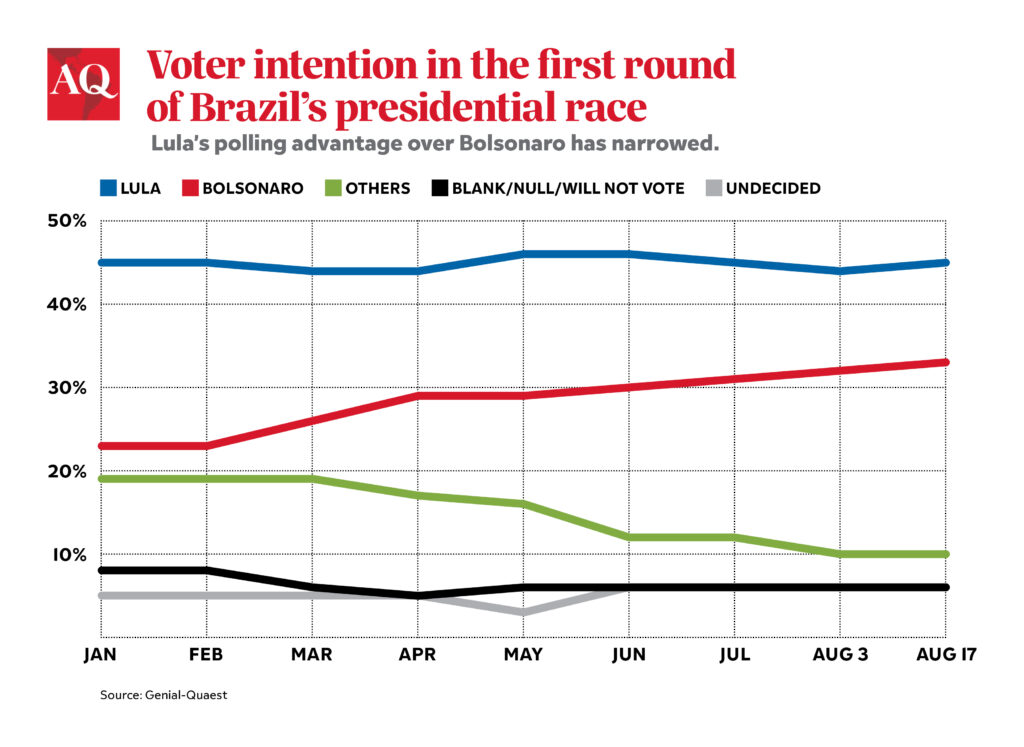

It is still possible that Bolsonaro wins this election. Polls have shown a significant narrowing of the race since March, although Lula retains a comfortable lead of seven to 15 percentage points in most. Brazil’s economy is improving, with unemployment falling below 9%, its lowest level since 2015, while inflation has also apparently peaked. Bolsonaro has pumped billions of dollars into the economy to boost his chances, including a 50% increase in the payout of Brazil’s main social welfare program. His social media machine remains formidable and unscrupulous. Evangelical Christians, so key to his 2018 victory, seem to be rallying once again to his side.

But time is running out, and the most likely scenario remains a Lula victory. Some of Bolsonaro’s allies have told me (and others) that the president would willingly transfer power to anyone else—but not the leftist who governed Brazil from 2003 to 2010, then spent time in prison until corruption charges against him were overturned by the courts. “We all want democracy, but giving power back to a criminal like Lula would be the end of democracy in Brazil,” one source said. I do not agree, but that is how many bolsonaristas see the stakes. And they are preparing to act accordingly.

One strategy would be for Bolsonaro to follow in Trump’s footsteps, and try to reverse the election result in the courts. But Brazil’s Electoral Court has repeatedly ruled against Bolsonaro, and the centralized (and efficient) nature of vote-counting makes challenges much more difficult than in the patchwork U.S. system. That leaves the option of claiming fraud in the court of public opinion and hoping the “people” and/or the Armed Forces will support his claim to stay in power. But it’s one thing to contest, say, a two-point loss—and quite another if the margin is five or greater, as polls currently suggest. That’s why many believe that Bolsonaro will try to force a “Brazilian January 6” before the election, possibly as soon as September 7, the 200th anniversary of Brazil’s independence.

That day, Bolsonaro has invited thousands of his supporters to Rio de Janeiro to attend an event on Copacabana Beach that will feature extensive participation by the military—including troops parachuting onto the shore, 29 cannon shots, and a procession of Navy boats. As I write this, there are widely divergent visions of what will happen and what it will all mean. Some well-placed sources point to the military’s apparent refusal to stage its traditional Independence Day parade at the event as proof that senior commanders do not want to politicize the proceedings and are seeking distance from a doomed president. Others argue that, regardless, the event will still be seen by the Brazilian public as a decisive show of military support for the president, setting the stage for the real showdown later on.

I am quite certain we will not see a traditional coup on September 7. But an emboldened president might, for example, declare in his strongest language yet that he expects the election to be rigged, or demand that it be postponed unless his requests for changes are met. As for the military, a major political risk consultancy recently issued a 38-page PowerPoint assessing the loyalties of individual generals and their support for a potential “questioning of democratic institutions.” Their final takeaway was that most key figures would support the Constitution – but the fact this report was even written tells you exactly where we are in 2022.

The remainder of Brazil’s establishment is not watching all this passively. The recent inauguration of the new president of the electoral court, Justice Alexandre de Moraes, amounted to a huge show of support for Brazil’s democratic institutions—with ex-presidents, governors and members of Congress applauding Moraes as Bolsonaro sat there petulantly. Several influential members of the business community were among the 1 million Brazilians who have signed a manifesto declaring that “in today’s Brazil, there is no more space for authoritarian setbacks.” In Brasilia, many treat these as signs the president has already lost. “Bolsonaro can do or say whatever he wants,” one former minister told me this week. “But nobody will go with him. It’s over.”

Maybe. But Bolsonaro retains the fervent devotion of millions of people who believe they too are acting to save democracy. Many of them, uniformed and otherwise, have guns. As we think about what’s ahead, I personally am torn between two competing views. One is that Bolsonaro could go where even Trump didn’t dare, and simply refuse to leave the presidential palace—declare the vote illegitimate, surround himself with armed allies, and essentially say “I’m still the president, and if you don’t like it, come and get me.” But the other view is that, over the last four years, whether it’s been the economy, management of the pandemic, or anything else, the defining characteristic of Bolsonaro’s presidency has been disorganization. He may simply lack the popularity and logistical skills to pull off a power grab under these circumstances. And that is why, sitting here today, I believe that Brazilian institutions will probably prevail in the end. But it could still be an incredibly messy, possibly violent, protracted crisis of democracy—in a Latin America, and a world, that has already had far too many of them.