SANTIAGO — The causes were complex, but one thing is crystal-clear about the prevailing mood here since massive street protests erupted in October 2019: Chileans want change. The installation of a constitutional convention and the election of President Gabriel Boric represented the two most important responses to these demands. And yet both got off to a difficult start. If it is true that there’s never a second chance to make a first impression, this could end up being an enduring, and severe, problem for both.

Boric took office just over a month ago amid a wave of optimism and goodwill. Thirty-six years old, energetic and empathetic, he seemed to embody the change that Chileans sought. His election platform was a catalogue of issues that have long been ignored in Chile, with a special emphasis on inclusion. His political appointments, the cabinet, ambassadors, and other positions, included a historic number of women and diverse perspectives.

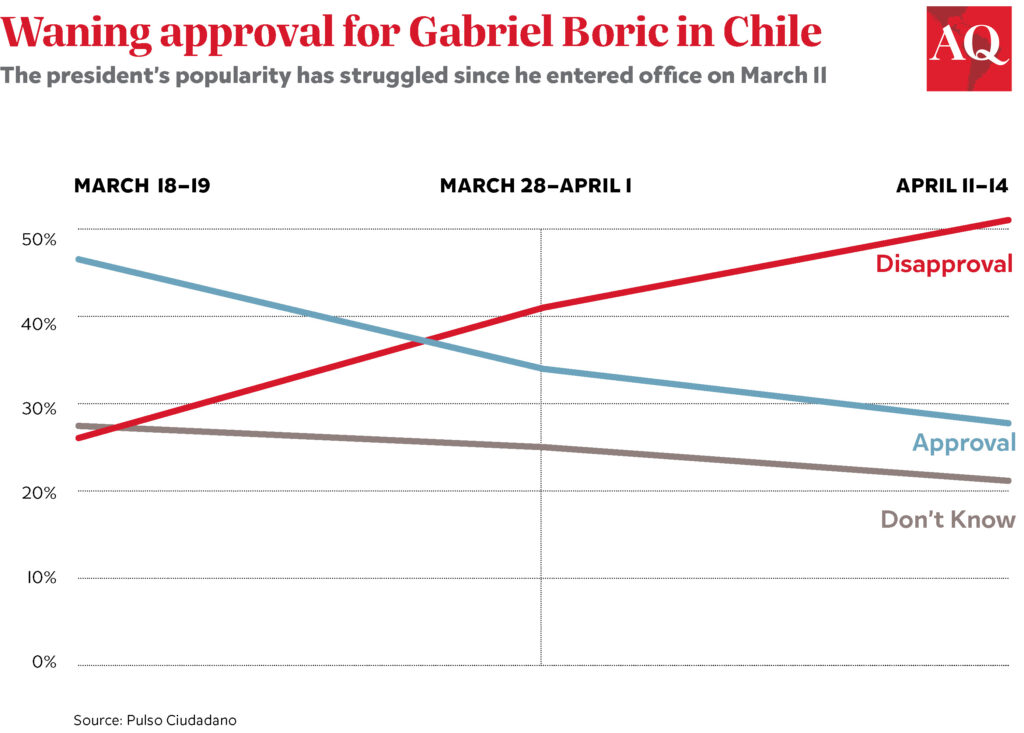

But Boric also faces serious headwinds, as evidenced by a recent poll by Pulso Ciudadano showing his approval has already fallen to just 28% (another poll, by Cadem, puts the number at 40%). It is becoming clear that the public discontent and distrust that gave rise to the 2019 protests never really went away. Rather, they were channelled towards a process of political change, contained in part in the constitutional convention. At the same time, public opinion is very much expecting results, and quickly. Perhaps more quickly than any government would be able to meet.

Some of the criticism has come from unexpected quarters. Indeed, the president’s coalition of new progressive parties and the Communist Party is an uneasy one. His former adversary in the primaries, Daniel Jadue, has been a constant critic from the left, most recently complaining that the president “has never considered overcoming capitalism and neoliberalism.” This, after having travelled to Caracas to rain praise on Maduro and the Venezuelan regime, of which Boric has been a vocal critic.

Boric also faces a divided Congress, where getting legislation passed will prove to be a challenge. The economy continues to struggle from the double effects of political uncertainty and the pandemic. The IMF this week adjusted its growth forecast for Chile to 1.5% for 2022 and 0.5% for next year. The Chilean Central Bank is even more pessimistic. Inflation, already rising thanks to the pension withdrawals approved in the previous administration (the fourth of which the government managed to shoot down just this past week) and other government transfers, has been further boosted by the war in Ukraine, and is on track to hit 7.5% this year (the price of sunflower oil, at about $4.50 US a liter, has become synonymous here with the rising cost of living). Interest rates have climbed from 2.75% to 7.5% in only a few months. The effects on Chileans’ pocketbooks, and on government approval, is already evident. Boric’s approval rating is far below where most Chilean presidents are at this point in their first terms.

A learning curve

All of these problems (except perhaps Ukraine) were predictable. So was what has turned out to be Boric’s biggest challenge: the learning curve. Boric is an extremely talented politician and a great communicator. Despite his young age, he has been in politics for the better part of a decade, and if you include student politics, longer than that. But none of that prepares one for government.

All governments, everywhere, face a learning curve, especially those that enter office promising change and generational renovation. Think of Bill Clinton’s first administration. And so it has been with Boric, who leads a coalition with no executive experience. With only one or two exceptions, his ministers are first-timers, and it shows. The most obvious case is that of Izkia Siches, his 36-year-old interior minister, who rose to prominence as president of Chile’s College of Physicians during the pandemic, but has no political experience. Since taking office, she has made a number of mistakes. In her first week, she travelled to the southern district of Araucanía, hoping to dialogue with radical indigenous groups who have been conducting often violent raids on civilians. Her caravan was met with gunfire, and the minister had to retreat. More recently, speaking at a congressional committee, she repeated as fact a discredited rumor that essentially accused the previous government of a crime it did not commit. The minister quickly apologized, but the damage was done.

The image many Chileans currently perceive is of a government of well-meaning but inexperienced young people whose ideology is colliding with political reality. Bill Clinton managed to correct initial mistakes in part by shifting to the political center. It is unclear, given the government coalition and the overall public mood, whether Boric has much space to do the same (although it is interesting to observe the role of the Socialist Party as a conduit between the new young Turks and the social democratic old guard).

The constitutional convention may be going through a similar challenge. Over the last few weeks, the plenary has begun to vote on the final text, accepting or rejecting articles approved by the various committees. With some 240 articles already approved, the final text—to be voted on in a referendum on September 4—is taking shape. Perhaps for this reason, the public is beginning to make up its mind, and it does not look good. For the last three weeks, according to the Cadem poll, more Chileans are in favor of rejecting the new constitution than approving it (45% versus 38%). How could this be?

Again, it seems that political reality trumps ideology. It may be that the public sees the convention as being out-of-touch with society as a whole. Much of the discussion so far, and the articles approved to date, deal with a new kind of decentralization (the design of which few understand or care about), the elimination of the Senate (to be replaced by a Council of Regions whose precise attributes remain undefined), and throughout, an emphasis on gender parity and indigenous rights. Yet when asked in a Cadem poll, what they believed the most important issues to be included in a Constitution ought to be, only 2% thought it should be a plurinational state and 3% said decentralization. Guaranteeing social rights—health, education, etc.—was the number-one answer at 62%.

These rights were partially approved this week (many of the specifics were sent back to committee), and it will be interesting to see whether future polls show a more positive evaluation of the constitutional draft. The question, both for the constitution and for the Boric government itself, is how much damage these first impressions have done.

Possible scenarios

How will this all play out? Both the convention and the government still have time to show that they know how to respond to the public’s demands, beyond their particular sectarian preferences. If Gabriel Boric has proved anything over the last year, it is that he is pragmatic, and will adapt to changing circumstances. The president has said that the fate of his government is linked to the fate of the constitutional convention.

There are at least three scenarios for which the government must be prepared.

The first is broad approval, which would be a success for Boric, but could end up being a headache, as he will have to implement a most unusual institutional structure. He might even be removed in early elections (the process allows for this). Second, there might be a very tight approval, say, with a margin of one or two percent. This would severely hinder the legitimacy of the new document. Third, if the polls are to be believed, a rejection of the draft in September. Calls for a Plan B have already emerged, although for now they come from the defeatist right than from progressives who want to see a successful constitutional process. The only way forward would be to immediately announce some kind of new, but different, process to come up with a more acceptable draft, extending institutional and economic uncertainty for many months to come.

—

Funk is a professor of political science at the University of Chile and a partner in Andes Risk Group, a political consultancy firm.