These should be happy times for Chile. Three decades of democratic rule have fostered development and reduced poverty, and expectations are high as a new generation prepares to replace the old political guard. On March 11, the 36-year-old former student leader Gabriel Boric will be inaugurated president. To top it off, a new constitution should be in place by the end of the year, provided the text now being drafted by a constitutional convention is approved in a national plebiscite.

So why is the new constitution raising alarm bells?

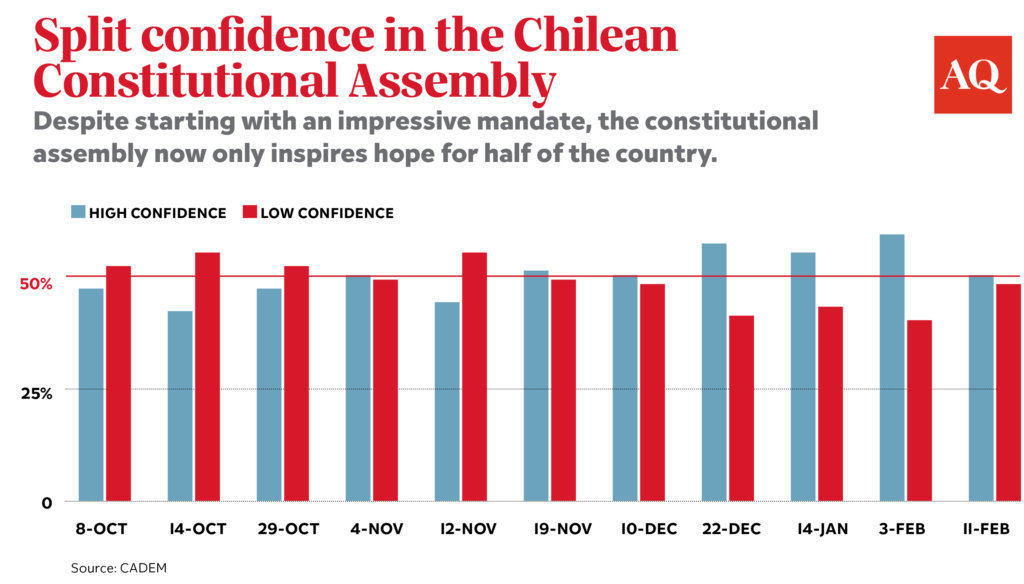

Deliberations over the document, which began in July 2021, have entered a critical phase, with some key articles already approved and others coming to the floor for consideration. As they do, it has become increasingly clear that the foundational spirit of the convention represents a risk to Chilean governance.

At the heart of the issue is that most convention members believe Chile needs drastic change. Rather than start by reviewing previous constitutions and national constitutional history to decide what to keep and what to discard, the convention chose to draft their document from a blank sheet of paper. Many convention members are determined that nothing of the current constitution – adopted under military rule but modified almost 50 times after democracy was restored – should be present in the next one.

Letting their creativity run wild, the convention has come up with ideas and concepts that have never been tested or, even worse, have failed wherever they’ve been tried. The document now taking shape is an attempt to anticipate every possible future scenario, satisfy every constituency and achieve every social goal. The result is by turns silly and by others deeply concerning for Chile’s long-term political and economic health.

Some of this is baked into the process itself. Nine constitutional committees have drafted articles based on proposals by convention members or public petitions. In recent weeks those committees have begun voting on thousands of proposals, sending those that are majority approved to the convention floor. There, a 2/3 majority is required for a proposal to make it into the final text. If a proposal fails, it goes back to the committee for amendment before a second, final vote. The 155-member convention has the last word, but if committees do not to send articles on a subject, or if articles don’t get a 2/3 majority in the second vote, the new constitution will not include any language on the issue at hand. That almost certainly means a long process of filling in constitutional gaps will remain after the new text is enacted.

The high 2/3 majority threshold initially led many to expect a minimalist constitution like that of the United States. But the process looks more likely to produce a long, comprehensive and extremely detailed constitution that will rival in length other constitutions written in Latin America in the last 40 years.

Indeed, every political institution in Chile is under threat of elimination or deep redesign. While convention members have avoided the word “unicameral,” the new constitution may significantly weaken the upper chamber of congress. The convention is also trying to give more power to Chile’s 16 regions (a number that could increase to 20 if proposals to create new regions gain support). Defying all evidence from countries that have tried fiscal decentralization, the constitutional convention has already included text that will give regions the power to issue bonds, levy taxes and run their own finances.

Ignoring the importance of protecting property rights for economic development, the convention committees have approved provisions that will make investors think twice before putting their money in Chile. Some provisions already sent to the floor for a full vote call for the nationalization of the mining sector. Others make eminent domain so broad that citizens would have no protection against a government that wants to nationalize the entire economy. Those provisions would still need to be approved by the floor, but the fact that they have made it this far suggests big changes on the way for Chilean property rights.

Proposed changes to the Central Bank will also be sent to the floor in the next few weeks. Although it will likely remain independent on paper, the five-member Central Bank board will get additional members – with a gender parity condition and special seats for indigenous representatives. In addition to controlling inflation, the new Central Bank mandate being discussed at the committee level looks likely to include the promotion of employment and job creation, protecting the environment and securing equitable regional development. Such a plethora of obligations will inevitably generate contradictions and uncertainty as to what the Central Bank is really meant to do.

And where on one hand the convention is discarding traditional political institutions, many of which existed long before the 1973 democratic breakdown, on the other it is pursuing social goals with such a broad brush that it could harm Chile’s economy and hamstring Boric and other future presidents’ priorities.

For example, ambitious provisions for the rights of nature, expressed repeatedly in different articles already voted by the floor and many others approved at the committee level, will create huge hurdles for mining activities. Since mining remains Chile’s most important export sector, the convention might end up killing the goose that lays the golden eggs rather than finding ways to make sure that the golden eggs are equally distributed.

The convention is also going out of its way to prove its progressive credentials. Provisions already approved ensuring popular representation in the legislature for each of Chile’s 11 groups of native peoples are far more expansive than existing representation mechanisms for indigenous minorities elsewhere in the world – and will enshrine malapportionment rules that will distort the principle of one person, one vote.

What’s more, the legal language common in constitutions has been replaced by poetic writing obsessed with listing synonyms. The old judicial power will be replaced by a national system mandated to deliver “justice with a gender approach.” There shall be gender parity in the judicial system at all levels, meaning Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s goal of having a Supreme Court comprised entirely of women would be unconstitutional under the new text in Chile.

In short, the convention is repeating the mistakes of other recent constitutional conventions in the region by coming up with a document that will be insufficiently flexible to accommodate changes in future needs and priorities. That this comes as a new administration prepares to take power is all the more worrying. Boric takes office on March 11, but in effect will have to wait to fully assume his position until the constitutional convention completes its deliberations. If he were to act contrary to the convention’s wishes in one area or another, its members would be able to write text into the new constitution to force his hand.

The long list of social rights included in the new constitution will also force an increase in fiscal spending on top of what Boric already promised in his campaign. The incoming government has promised, for example, to forgive university tuition debt for hundreds of thousands of young people, expand affordable housing for the needy, including recent immigrants, and increase the government contribution to pensions. As a candidate Boric called for a tax increase of 5% of GDP in the coming years.

Chile’s constitutional convention was triggered by dissatisfaction with high levels of inequality. The country is among the most unequal in its GDP per capita bracket. Unfortunately, Latin America’s history teaches us that drafting new constitutions does little to reduce inequality. A maximalist and all-encompassing constitution, more concerned with redistribution than with generating wealth, will make life hard for the incoming government and, in the long-term, be a straitjacket that hinders development and social inclusion.

—

Navia is a contributing columnist for Americas Quarterly, professor of liberal studies at NYU and professor of political science at Diego Portales University in Chile.