This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on Latin America’s anti-corruption movement | Leer en español | Ler em português

It was such a feel-good story… in the beginning.

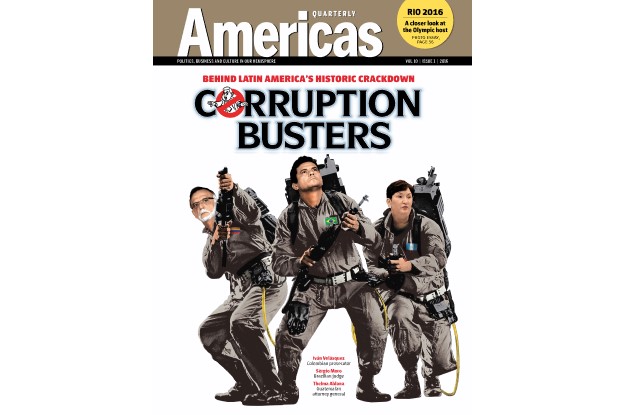

In January 2016, Americas Quarterly published a special report on corruption — with a catchy cover inspired by the movie “Ghostbusters.” Featuring Brazilian Judge Sérgio Moro, Guatemalan Attorney General Thelma Aldana and Colombian prosecutor Iván Velásquez, we were among the first to highlight how seemingly isolated scandals erupting in Latin America were part of a broader, potentially transformational trend.

Where are they now? Click above for an update on the “Corruption Busters” from the 2016 cover.

Where are they now? Click above for an update on the “Corruption Busters” from the 2016 cover.

Corruption wasn’t new; but so many powerful people going to jail certainly was. The timing wasn’t a coincidence, we argued. The spread of democracy throughout Latin America since the 1980s had given rise in many countries to more independent institutions — and a bold new generation of “Corruption Busters” like those we depicted on our cover. Since the 2000s, the region’s middle class had expanded by some 50 million people, contributing to a change in values — specifically, less tolerance of politicians who “steal, but get things done.” The rise of mobile phones and social media made corruption easier to uncover — and organize protests against. New global banking and transparency laws passed after the 9/11 attacks and 2007–08 financial crisis also played a role.

In a diverse region, some countries were clearly advancing faster than others. But overall, we argued that the successful prosecution of cases like Lava Jato in Brazil, La Línea in Guatemala and the Caval Case in Chile were helping to reduce the impunity that has always been one of Latin America’s biggest curses — a cause of inequality, violence and countless other ills.

Today, much of what we wrote remains true. But as Latin America’s anti-corruption movement has continued, its own risks, abuses and vulnerabilities have become impossible to downplay or ignore. Perhaps nothing illustrates this quite like what’s happened to the original “Corruption Busters” from our cover; all have, for different reasons, entered into a more difficult period in their careers (Click here to read more details). The leaks in June of private messages between Moro and Lava Jato prosecutors reinforced fears that many investigations have been plagued by political bias and a hypocritical disregard for ethics and the law. Others worry the seemingly never-ending gusher of scandals is paralyzing economies and causing citizens to lose faith in democracy itself.

How to make sense of all this? What is the state of the anti-corruption drive today, and how much danger is it really in? Is there a way to address the bad aspects — and salvage the good? To try to answer these questions, I spoke to more than three dozen jurists and political analysts across the region, dug into recent polling and came away with a few clear conclusions — and a mea culpa of sorts.

Latin America is a varied region. But there are three main trends that hold true in many countries and capture where the crackdown stands today:

1 | It remains very popular

This much is clear: Most Latin Americans still love seeing corrupt presidents, civil servants and business executives prosecuted and sent to jail.

Just a decade ago, corruption barely registered as a concern in most polls. Today, it is seen as the fourth-most important problem behind crime, unemployment and the economy, according to the most recent region-wide survey by Chile-based Latinobarómetro. But even that disguises great variations: Corruption was seen as the most urgent issue by Colombians, and it was number two in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia and Mexico. (In Argentina, Venezuela and Nicaragua, by contrast, other concerns took far greater precedence.) Other national and regional surveys portray a similar picture. In an Ipsos poll in 2018, a whopping 87% of Brazilians agreed the Lava Jato probe should continue “to the end, no matter what the cost.”

In perhaps the ultimate test of support, people are also willing to put down their phones and do something to further the cause.

In December, more than 80% of Peruvians voted in support of anti-corruption reforms in a referendum called by President Martín Vizcarra. In a similar referendum in Colombia in August 2018, votes in favor of anti-corruption measures (11.6 million) actually exceeded the number of people who cast ballots for Iván Duque (10.3 million) in that year’s presidential election. Street protests in favor of the corruption crackdown have continued to draw large crowds in Brazil, Guatemala and beyond.

This matters for a number of reasons. Grassroots support has often (though not always) helped dissuade politicians and other interest groups from trying to undercut or sabotage investigations. For example, when high-profile Peruvian prosecutors José Domingo Pérez and Rafael Vela were fired in December, a public outcry forced authorities to quickly reinstate them. The popularity of the Lava Jato probe in Brazil has deterred legislators from passing bills that would curtail the investigative powers of federal police or otherwise protect the powerful.

Even in countries where investigations haven’t advanced much, the desire for justice has had a major influence on politics. One example is Mexico, where anger over impunity and corruption under established parties helped fuel the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador and give his new party a majority in Congress. Ecuadorean President Lenín Moreno has made combating graft a centerpiece of his government, while El Salvador’s new leader Nayib Bukele has vowed a similar focus.

2 | The problems are real

2018 was a year of setbacks for anti-corruption efforts, and 2019 has been even worse.

In some instances, elites and entrenched interests have dismantled — or severely damaged—investigations in a cynical effort to protect the status quo. Often, they have cited alleged prosecutorial abuses or dubious technicalities as a pretext. This seems to have been the case in Guatemala, where President Jimmy Morales kicked out the UN investigative body CICIG in January, citing threats to national sovereignty, after CICIG helped investigate him and members of his family.

Allegations have mounted throughout the region that judges and prosecutors are motivated by political bias — using “lawfare” to target an individual or ideology, particularly those on the left. Some of this is clearly nonsense. In countries where the right was recently in power (Guatemala, Peru, Panama), conservative politicians have been the ones who went to jail; if leftist politicians are filling prisons elsewhere, remember the “pink tide” dominated South America for the last decade-plus. In Brazil, Lava Jato has resulted in more than 160 convictions, including numerous figures from the business community, and brought charges against members of more than a dozen political parties across the ideological spectrum. It has been often easier for the corrupt — and their supporters — to point fingers and cry bias than it has been to recognize their own mistakes.

In some cases, though, the decision to prosecute — or not — has indeed smelled of politics. Numerous observers raised concerns after a judge filed treason charges in 2017 against former Argentine Foreign Minister Héctor Timerman, who died of cancer in December; Human Rights Watch called the allegations “weak to the point of being ridiculous.” Many have also wondered why Odebrecht-related investigations in Colombia and Mexico have not been as broad or rapid as in other countries. Decisions by some judicial figures to seek political positions — such as Moro becoming Jair Bolsonaro’s justice minister, and Aldana’s short-lived campaign for the Guatemalan presidency — have exposed them (and their peers) to accusations that their work was political all along.

Elsewhere, prosecutors and law enforcement officials appear to have been motivated less by politics and more by an overzealous desire to catch their suspects at any cost. This is a tale as old as law enforcement itself. But whatever their motivation, some have crossed legal, procedural or ethical lines. Many point to the excessive use of pre-trial detention in corruption cases, especially in Peru, where one former president committed suicide rather than face it (Alan García), while another is under house arrest despite not yet being indicted on any charges (Pedro Pablo Kuczynski). Recent leaks involving Moro seem to show him coordinating with prosecutors in a way that many Brazilian jurists say was, at a minimum, unethical (Moro denies wrongdoing.) Some said the revelations could even contribute to the reversal of the 2017 conviction of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The question is whether other cases in other countries will also be put at risk.

Michel Temer’s March 2019 arrest on corruption charges showed that Lava Jato retains momentum five years in.

Michel Temer’s March 2019 arrest on corruption charges showed that Lava Jato retains momentum five years in.

3 | Scandals continue unabated

Five years after the start of the Lava Jato case, scandals have continued to erupt at a prodigious pace. Recent examples include the Notebooks scandal in Argentina, the Cementazo affair in Costa Rica and the Arroz Verde case in Ecuador, as well as a kickback scheme in Brazil that allegedly involved Bolsonaro’s son Flávio, a senator.

This is partly positive news. It means that prosecutors, investigative journalists and others continue to do their jobs; indeed, many have been inspired and emboldened by the work of their peers since 2014. But it also points to structural problems and incentives that cause grand corruption schemes to continue to proliferate. For example, reforms to campaign finance and lobbying, which could actually address the critical, problematic intersection of money and politics, have been slow to move forward in most countries (Chile is an exception). Meanwhile, some actors appear to believe that the anti-corruption wave is akin to a passing storm, and they can just batten down the hatches and wait for it to pass before resuming business as usual.

There is a bigger problem: Many Latin Americans seem to be interpreting all these scandals as a sign of democracy’s failings, rather than its strengths. Some still harbor the illusion that there was less corruption under the authoritarian regimes of the 20th century, when it’s evident that in previous eras corruption simply wasn’t uncovered and prosecuted to the same extent. Be that as it may, the damage is real: 71% of the region’s citizens told Latinobarómetro they were dissastisfied with democracy, up from 51% in 2009. Just 8% of Brazilians, and 9% of Mexicans, told the Pew Research Center last year that democracy is a “very good” form of government — the lowest of 38 countries surveyed. Economic stagnation and rising violence have also fueled this anger, of course. But many fear the consequence will be a rise of new authoritarian leaders; indeed, there are signs this is already happening.

A May 2019 protest in Brasilia featured a giant balloon of Moro as Superman.

A May 2019 protest in Brasilia featured a giant balloon of Moro as Superman.

Conclusions

The ultimate risk for Latin America’s anti-corruption drive is that it ends up like Mani Pulite, the “Clean Hands” scandal that shook Italy in the early 1990s. Hundreds of politicians were arrested, and nearly half of Congress was indicted—but fundamental practices never changed. A decade later most observers concluded corruption in Italy was just as bad as before; some studies suggested it was worse. In other words: There was no real point.

Considering all of the political and economic disruption brought by Lava Jato and similar probes, it would be a terrible shame if history repeated itself. Virtually everyone recognizes that corruption is a main reason why Latin America remains the region with the world’s biggest gap between rich and poor. It deprives governments of funds that should be used for education, healthcare and infrastructure. It also trickles down into the rest of society. Former Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo’s famous lament that his country’s top three challenges were “rule of law, rule of law and rule of law” remains true — and not just of Mexico.

For that to become reality, though, defenders of the corruption crackdown need to recognize the gravity of recent setbacks — and the danger the movement is in. Prosecutors and judges are not above the law; they must be treated with the same severity as the people they are investigating. Otherwise the public will continue to lose faith in the judicial system — providing an opening for the establishment to weaken it further. A poll taken immediately after the Moro leaks showed 41% of Brazilians believed the disclosures damaged Lava Jato’s reputation. It’s tempting to dismiss this episode as a one-off; but Brazil has frequently been at the forefront of the anti-corruption story, further down the road than its peers. Similar episodes are almost certain to occur in other countries.

The recent setbacks also point to perhaps the biggest necessity of all. In retrospect, turning prosecutors and other law enforcement officials into “superheroes” may have fueled a dangerous hubris — and a disregard for rules and norms. This magazine, and our 2016 cover, may have played a part in that, though we were hardly alone. Going forward, the focus must be less on individuals, and more on topics like building institutions and passing reforms. Otherwise, justice — and ultimately democracy itself — may recede once again.