LIMA — For most, the transformation that Peru experienced since 2016 is difficult to understand. Politically, we have had seven presidents in seven years, and our economy has made a 180-degree turn, from fast growth to recession in the first half of 2023. Identifying the underpinnings of this change is a challenging task.

There’s one group that sticks out as deserving particular blame. The corruption of construction companies since 2001 exposed almost all former presidents since Alejandro Toledo (2001-06), distorting our political system and parties, which became instruments to extract rents from the state, tipping Peru into crony capitalism.

Worsening the rot is a dysfunctional political system. Electoral districts are too large, breaking the link between representatives and the population. Our unicameral system lacks an upper house to oversee decisions made by the lower chamber, and a mixed parliamentary and presidential system sets up clashes between Congress and the executive. Peru passed new legislation in 2019 introducing open primaries within political parties and limits on campaign contributions. The former is due to start in the 2026 general elections, while the latter has been in place since 2021. However, a ban on running for office while undergoing penal investigations or for those with prior convictions has been harder to implement, and many tainted politicians have ended up in Congress or elected positions.

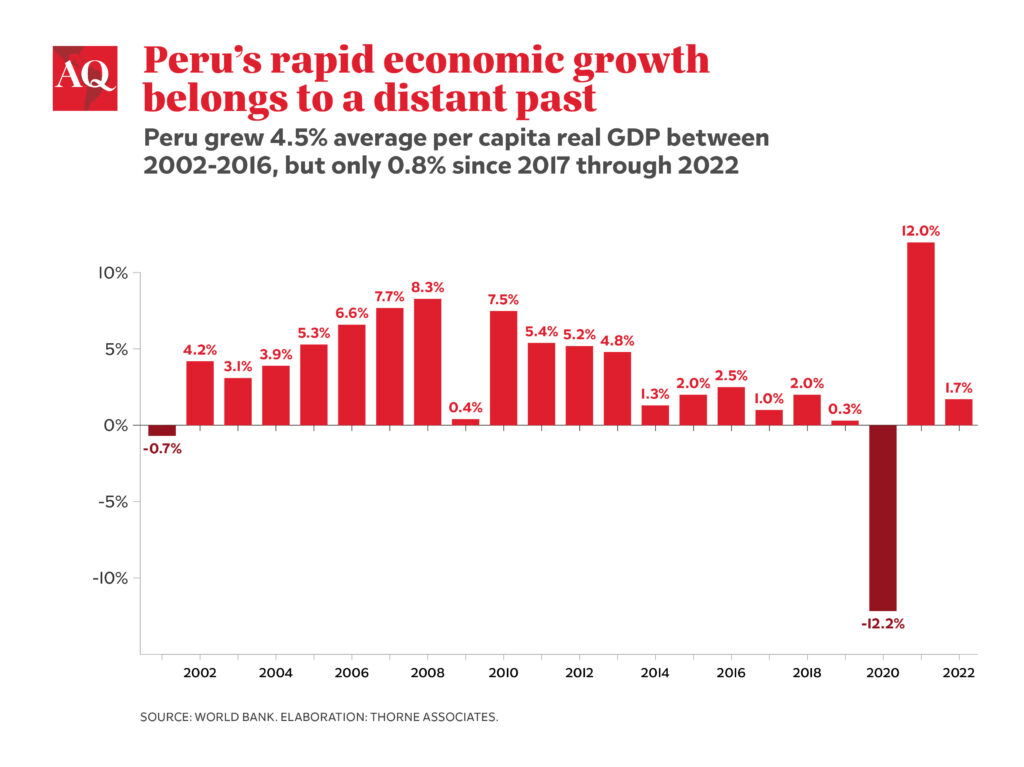

While all this is true, one might ask: Is that all? It’s hard to shake the sense that something more profound is wrong in Peru’s economy and society. Peru has been very successful since the 1990s in stabilizing the economy and laying the foundations for solid growth. The evidence lies in rapid growth since 2002, averaging 4.5% per capita through 2016—and the success of our poverty alleviation programs, pulling more than one third of the population from poverty.

A deeper social challenge

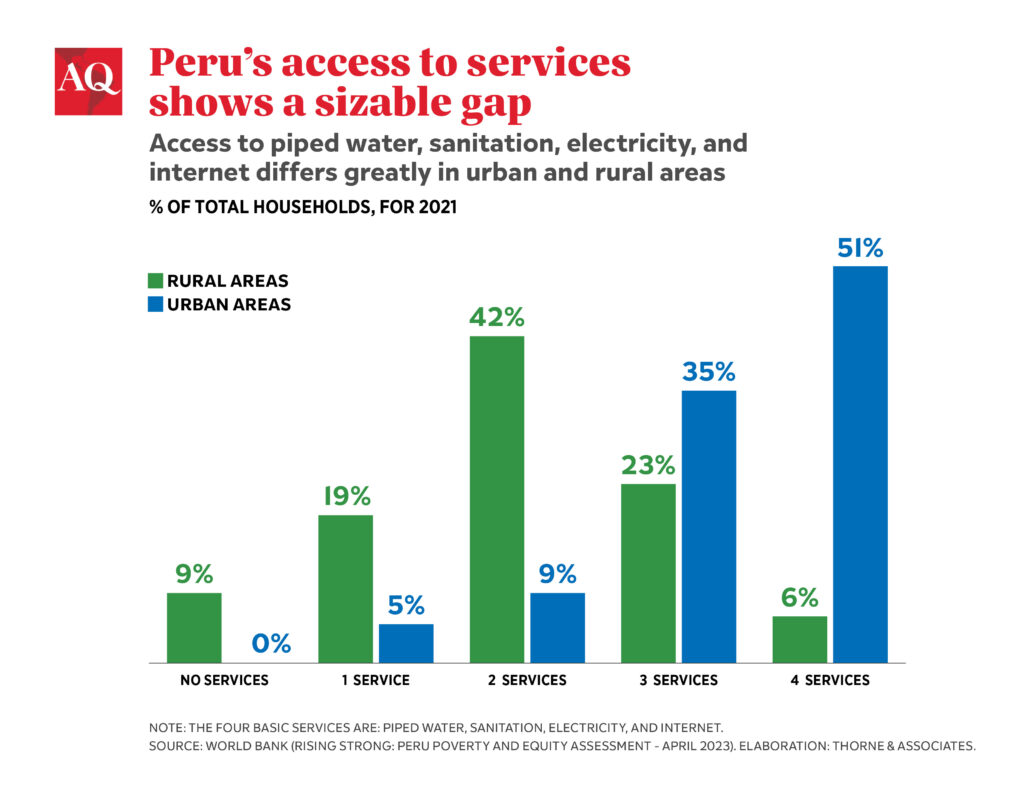

However, this economic development was uneven. According to World Bank studies, most of those pulled from poverty joined the “vulnerable” segment and failed to access permanent jobs. Of Peru’s 17 million-strong labor force, only 4.5 million are formal workers with full access to social protection. Finally, there is a significant equity gap between Lima, the capital, and the rest of the country, creating two worlds—you might call them the modern state and the informal state, respectively.

The sustainability of an economic model like Peru’s relies on high-quality education, a social safety net, and anti-poverty programs to ensure economic growth benefits disadvantaged groups, too. But efforts to secure these have failed. As politics became a world of confrontation between the two sides of Peruvian society, governments since that of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (2016-18) have engaged in economic populism, granting new benefits mainly to middle-income groups and undermining the growth drivers that had sustained the rapid economic expansion in the 2000s.

With most of the population living in this informal state, our representatives came from this world, and the nation, during Pedro Castillo’s government, threatened to become a failed state: Peru almost became the new Venezuela.

In the meantime, there was little focus on structural reforms that could increase productivity growth. The outcome was a sharp decline in the country’s potential growth rate, the rate at which the economy could grow had it used its factors of production at total capacity, to only 2.6%, from over 5% in the early 2000s. With the economy decelerating, informality surged as differences between Lima and the provinces widened, small and medium enterprises suffered, and demands for government support increased. Corruption investigations had brought the state to a near standstill, and more and more government resources were allocated to current expenditures.

Boluarte needs legitimacy

Appointed president after Castillo’s removal after his attempted coup in December, Dina Boluarte inherited a complicated political system and economy—but she has also made essential mistakes, like failing to appoint an independent commission to investigate deaths during protests that followed Castillo’s removal. Her biggest failures are missing this opportunity to gain legitimacy and lacking a connection to the population. She has been exposed to pressure from Congress and other groups by doing so. Meanwhile, she seems more concerned with ensuring she stays in government through July 2026—when the new general elections are due—than with pressing issues like economic deceleration and faltering security.

Still, the economy has retained three positive, long-term anchors. The central bank’s independence has become an anchor for monetary stability. The commitment to fiscal discipline has been adhered to by most governments regardless of ideology—including left-wing Castillo. Finally, a vibrant private sector has remained intact. This commitment to market discipline is even shared by small producers who see their prosperity in linking themselves to the global supply chains. Peru’s multiple free trade agreements have helped it connect with the rest of the world. The new Chancay port, in the north of Lima, connecting Peru with Asian countries, to be inaugurated at the 2024 APEC meetings, could catapult us even more in this direction.

These anchors could play to the advantage of a potential pro-market government, should one win the 2026 general election, allowing for a resumption of the economic reforms that led to the rapid growth in 2001-17. Hopefully, this time, an equally important social reform will accompany them.

In the short term, these positive forces have not prevented the economy from falling into a technical recession in the first semester, when real gross domestic product contracted by an annual rate of 0.5%. The government has done little to induce a recovery. Through July, relative to 2022, government consumption fell 3.4% and investment 2.4%. The recently released July accurate GDP report confirmed that the economy fell 1.3% and signaled little signs of recovery in the current quarter. Officials have attributed continued troubles to exogenous shocks, including protests and El Niño.

The truth is the downturn is more profound than many wanted to acknowledge: Private consumption and investment have decelerated sharply, spurred by low expectations related to political instability. Most anticipate more effects from El Niño starting in November and lasting through March. Although we expect a recovery in the second half (1.1% growth rate), but this will be mostly due to base effects. This week, we cut our real GDP growth forecasts to only 0.4% for 2023 (from 0.8%) and 2% (from 2.6%), lower than the central bank’s recent downward revision of 0.9% and 3%, respectively.

Boluarte faces the challenge of gaining legitimacy by confronting the problems that face the population at large. But her isolation may cause her to become a lame-duck president and one vulnerable to those still trying to extract rents from the state for themselves and their supporters: a process that has already cost this once prosperous and promising nation dearly.