SÃO PAULO — Until recently, the 8% of Brazilians who live in favelas were almost completely left out of the country’s e-commerce boom.

Because of security risks, and the fact many residences lack easily identifiable addresses, most shipping companies refused to deliver to places like Paraisópolis, a community of about 40,000 in southern São Paulo. Residents instead ordered packages to their workplace (as long as the boss was cool), or the houses of friends in other parts of town.

That changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, when local resident Giva Pereira founded Favela Brasil X-Press. Building on a system used to distribute food and basic goods during the lockdown, and similar projects elsewhere in Brazil, the company receives packages at a small distribution hub in Paraisópolis. Employees who live in the neighborhood sort the products in a caged holding pen, and then hand-deliver them using Google Maps coordinates.

Favela Brasil X-Press performed 1.5 million deliveries last year of merchandise worth an estimated 1 billion reais, or about $200 million. The company, which receives fees from shippers to perform the “last mile” service and is profitable, has 250 employees working in six favelas around Brazil.

“It was common sense, but somebody had to make it happen,” Pereira, who is just 23, told me.

Such efforts are a welcome boost during a difficult – and frankly, disorienting – time for the poorest segments of Brazil’s population.

On the one hand, Brazil’s GDP grew almost 3% in 2023, unemployment fell to a 10-year low, and real wages rose almost 4%. Leftist President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva revived several social programs during his first year back in office.

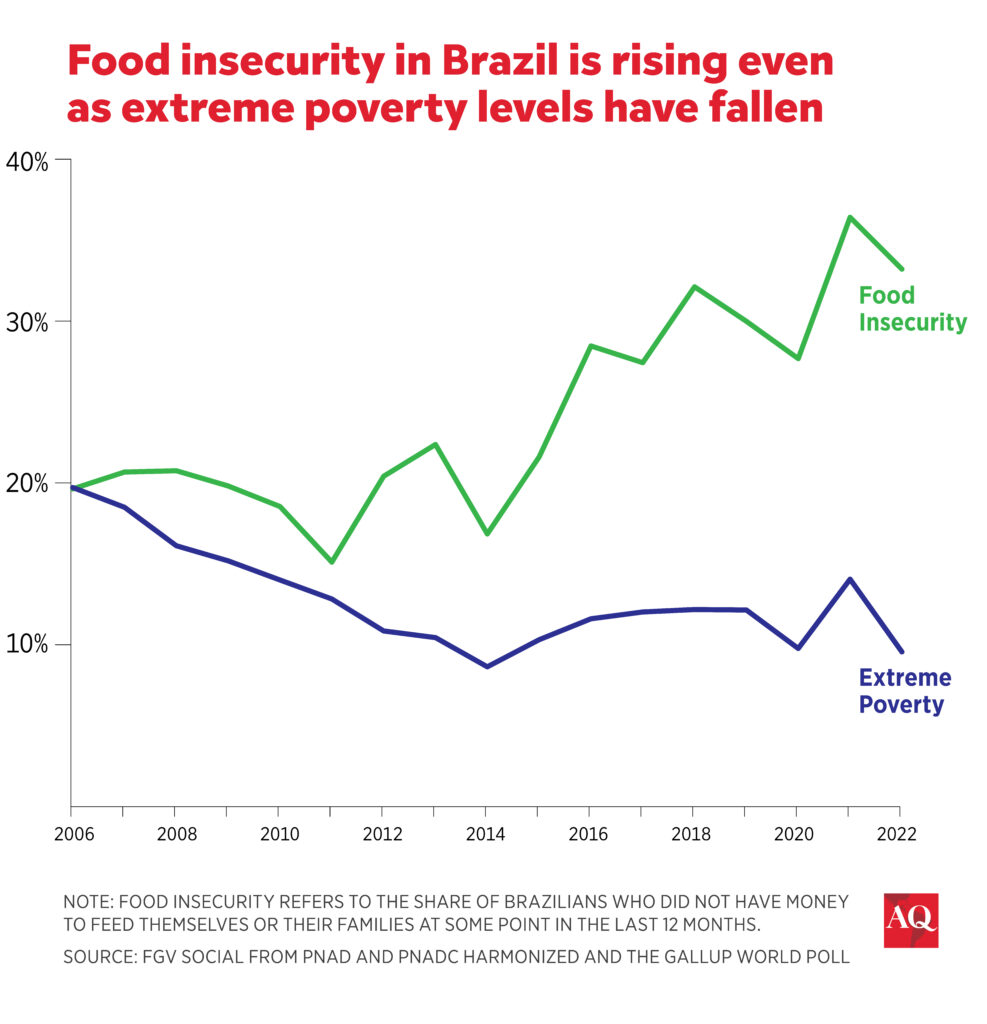

But about one in three Brazilians still say they sometimes cannot afford to feed themselves or their families – significantly more than a decade ago. As any resident or recent visitor to São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro can attest, the number of people experiencing homelessness in Brazilian cities has relentlessly grown, from an estimated 106,000 in 2014 to 281,000 in 2022, according to Ipea, a government-affiliated research institute.

This partly reflects social dislocations seen all over the globe in the wake of the pandemic. But there seems to be an additional Brazilian element: The wreckage of the 2015-16 economic collapse, and the political dysfunction that followed. While Lula has restored a certain governability in Brasilia, it may still take time for benefits to accrue to the working class.

In the meantime, residents of Paraisópolis have it better than some. On a recent Monday afternoon, kids in crisp uniforms were walking home from school. Stores sold meat and cheese pasteis, the Brazilian version of the empanada, as well as Barbie backpacks and basketballs. Unlike many favelas, the government was clearly present: signs touted the importance of “menstrual dignity” and a federal housing program.

Some of the progress is due to G-10, a not-for-profit organization founded by another Paraisópolis resident, Gilson Rodrigues. Its modern complex includes an organic garden where residents are taught basic horticulture; a development bank funded partly by Brazil’s central bank; a bakery; a podcast-recording studio; and a textile shop that produces uniforms and other items for Latam Airlines and other companies. It’s funded by a mix of corporate and individual donations, as well as revenue from its various operations.

The name was inspired by the G-20 – which coincidentally, Brazil is hosting this year. “I wanted something grand, a confederation of 20 favelas,” Rodrigues, 39, told me. It now has members in 402 favelas, “but it’s too late to change the name,” he said with a laugh.

Rodrigues’ story is dramatic. One of 14 children born to a mother who could not see or hear, he was orphaned at age nine and then spent three years sleeping underneath a table in a local bar.

After going back to school, he started working with community organizations. That led him to reach out to major Brazilian businesses, lobbying them to look past stigmas and security risks, and open operations in favelas like Paraisópolis. Some 16 million people live in Brazil’s favelas, almost as big a population as the state of New York, with a consumer power estimated at as much as $40 billion a year.

Many companies took the plunge, and Rodrigues’ profile grew. In 2022, he rang the bell to open trading at the New York Stock Exchange. Both he and Piva will travel to Boston and New York in coming weeks for the annual Brazil Conference held by Harvard and MIT.

Despite such successes, the stigma remains. I tried and failed to convince three Uber drivers to take me to Paraisópolis. Some local friends rolled their eyes and advised me to be careful when I told them of my intention to visit.

Rodrigues’ message is that people in Brazil’s favelas can improve their lives – especially if they have less discrimination, and more access to capital. “I don’t want any of this ‘poor them, oh they’re victims’ rhetoric,” he said. “What we need is a different vision of favelas. People need to see us as people.” In today’s political and economic environment, that’s as good a strategy as any.

(With research by Emilie Sweigart)