Lately, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum has been winning praise on both sides of the Mexico-U.S. border for her approach to combating organized crime. It’s not hard to see why: She has extradited more than two dozen cartel leaders, destroyed numerous fentanyl labs, and seemingly made progress in reducing the national homicide rate. At home, approval of Mexico’s approach to public security has risen from 28%, just before Sheinbaum took office in October, to just over 50% last month.

That support also shows in Sheinbaum’s 85% approval rate overall, making her one of the most popular leaders in the world. There’s no doubt we are living through a Claudia Sheinbaum moment. However, if we take a closer look into her fentanyl-focused security strategy, it comes with a risk: In focusing on headline-grabbing raids and extraditions that smooth over relations with the U.S., there’s a chance that the forms of violence that affect Mexicans’ daily life the most will be neglected—things like disappearances, forced recruitment into organized crime, and extortion.

So far, Sheinbaum has followed the agenda set by her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), on several key issues, combining welfare programs with austerity and support for national oil company Pemex. But her strategy for combating organized crime represents a significant departure.

AMLO’s approach to public security was encapsulated in his famous slogan, “Abrazos, no balazos” (hugs, not bullets), arguing that by enrolling youth in his welfare programs, he could keep young Mexicans out of the reach of the cartels. At the same time, he significantly reduced the force with which the Mexican state confronted organized crime because—he argued—“violence generates more violence.” But these security policies arguably became AMLO’s biggest failure. His six-year term ended with almost 200,000 homicides and polling consistently showed that this was the area in which citizens most questioned his otherwise widely approved government.

Praise for Sheinbaum

By contrast, Sheinbaum’s strategy, implemented by Security Secretary Omar García Harfuch, focuses on enhancing the intelligence networks of the Mexican state. It emphasizes strategic actions against the most violent groups, the prosecution and capture of logistical leaders and the “violence generators” of criminal organizations, while also calibrating regional tactics to address local issues. In other words, AMLO’s laissez-faire approach has been set aside, and public security again ranks as a top priority on the state’s agenda.

Sheinbaum’s policy shift on crime-fighting has sparked optimism in Mexico’s business community and press. And U.S. voices from President Donald Trump to The New York Times have praised Sheinbaum’s strategy to combat organized crime in general and fentanyl trafficking in particular.

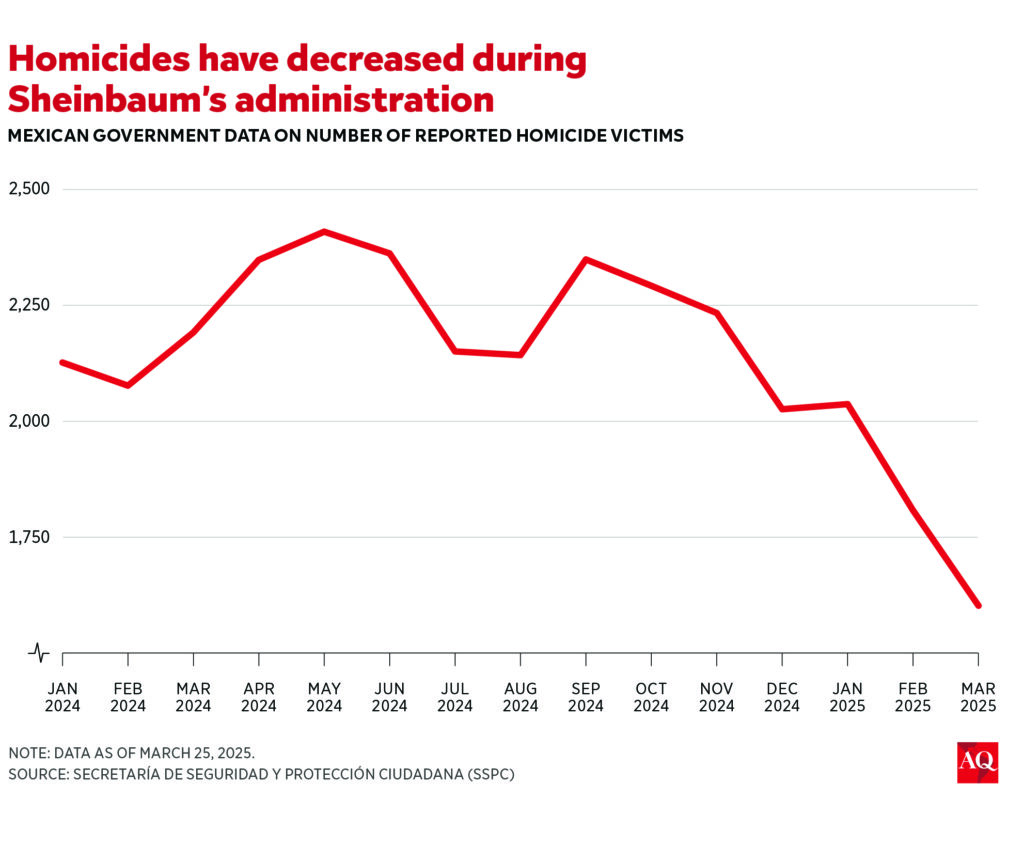

There are real accomplishments to point to. In late March, the government reported a 22.4% decrease in homicide rates between September, just before Sheinbaum took office, and March. That’s been paired with the seizure of 134.7 tons of drugs, including over 2 million fentanyl pills, as the government has dismantled 644 clandestine drug labs across 17 states and prosecuted criminals linked to fentanyl distribution.

Will Sheinbaum’s approach make a real difference?

In practical terms, Sheinbaum’s security strategy has two main goals: tackle fentanyl trafficking to conciliate Trump (and therefore avoid tariffs) and reduce the national homicide rate. On the first score, the strategy has apparently been successful. But research into how drug demand and supply really works suggests that a militarized approach to targeting production won’t necessarily put an end the U.S.’s appetite for fentanyl, nor its ability to get it. Drug markets are complicated business networks—and it is not enough to militarily attack production to end consumption, since the centers of production and distribution can shift geographically (as happened with cocaine production from Peru to Colombia and from there to Mexico).

As for reducing the homicide rate, it is still too early to judge if this strategy will be sufficient to contain violence overall. García Harfuch is placing a strategic focus on criminals who are planners, mobilizers, and perpetrators of violence against civilians—which is promising, because previously the Mexican state focused on capturing cartel leaders, not mid-rank members who are usually “violence professionals.”

Armando Vargas, the top security expert at the think tank México Evalúa, claims that the data Sheinbaum shows in her morning press conferences “aren’t useful to sustain that our country is on the road to pacification.” He argues that Mexico’s local police forces and prosecuting offices artificially lower the homicide figures, due to delays in reporting their numbers to the federal government, and their slowness or reluctance to classify potential murder cases as homicides.

Criminal organizations can also artificially lower murder rates by disappearing their victims’ bodies. Causa en Común, a think tank dedicated to civil liberties, democracy and public security, has claimed the federal government cherry-picks data on violence to portray its strategy in a positive light. This raises worries that official homicide rates may not be a reliable indicator of the level of violence in Mexican society—and other forms of violence, such as forced disappearances, extortion, coerced recruitment, torture, and human trafficking, could be increasingly ignored in the public conversation.

Challenges in measuring success

A focus on national figures also fails to account for local dynamics. While the national homicide rate may be decreasing, there can be regional outbreaks of violence triggered by disruptions in drug trafficking networks and the capture of high-ranking cartel leaders.

This was recently the case in Sinaloa, following the arrest—by U.S. forces—of Mayo Zambada, one of the historical leaders of the Sinaloa Cartel. According to the local newspaper Noroeste, between September and March, nearly 4,000 vehicles have been stolen, and close to 1,200 cases of abduction have been reported, along with more than 1,000 homicides, as a result of the wave of violence sparked by Zambada’s capture.

Sheinbaum’s crime-fighting strategy puts little emphasis on Mexico’s severe ongoing crisis of forced disappearances, and has proposed solutions that human rights experts say have failed in the past and don’t take into account the victims’ perspectives. The current number of missing persons is estimated at over 120,000, as criminal organizations have made disappearances a core part of their modus operandi. Following the recent discovery of a massive clandestine crematorium in Jalisco, organizations representing the families of missing persons have described the federal government’s response as “indifferent” and “disappointing”.

The organizations trafficking fentanyl to the U.S. are not always the same groups that have established violent extraction schemes in local economies through extortion and co-optation. So prioritizing the fight against fentanyl trafficking risks sidelining states such as Chiapas, Guerrero, and Tabasco, places not key to fentanyl trafficking but where criminal groups have escalated violence to tighten their grip on local economies.

Sheinbaum’s security strategy has already produced positive results, and it could further reduce fentanyl trafficking and weaken drug cartels. However, without prioritizing human rights and addressing forced disappearances, without meaningfully engaging with, and listening to, victims, and without tackling the everyday violence stemming from criminal control of local economies, her administration may fall short of resolving Mexico’s violence crisis.