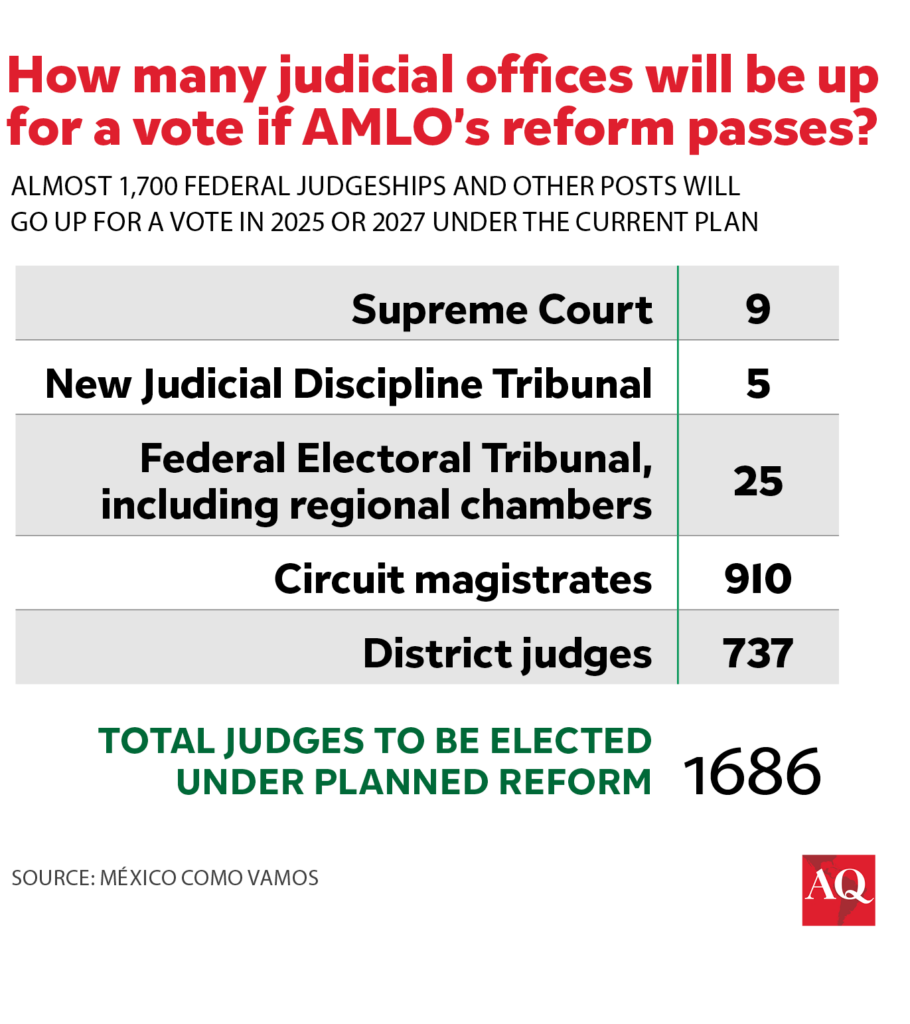

It’s a watershed moment for Mexico’s judicial system: A reform pushed by outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador would replace the entire Supreme Court and pick a new set of justices—as well as some 1,600 federal judges and magistrates—through a series of popular votes.

The most prominent opponent is Norma Piña, 64, the first woman ever appointed to head Mexico’s Supreme Court. She’s fighting not just for her own job but, she says, for the credibility and independence of the judiciary itself.

“We need an independent judiciary, staffed by people with solid preparation,” Piña said at the closing of an international gathering on judicial independence on August 14. Such an “abrupt” reform, she said, “could delay justice for citizens who are seeking resolution.”

But her bid to resist the reform doesn’t seem to be going well.

Amid accusations that Piña has played too political a role in opposing the reform, neither López Obrador nor Claudia Sheinbaum, his protégée who won an election in June to succeed him, have shown much interest in dialogue.

If Piña fails, the final hurdle will be Mexico’s Congress. But here, too, the odds seem stacked in the ruling party’s favor: The new Congress, with a larger Morena majority, takes office on September 1. That’s a month before AMLO’s term expires—giving him a window of opportunity to pass the reform the way he wants.

“The coming weeks will be key,” said Andrea Rovira, vice-president of the Ilustre y Nacional Colegio de Abogados de México, a national bar association. Morena’s potential supermajority in both houses is still pending final confirmation, and AMLO might choose to prioritize other reforms during September.

The proposed judicial reform would reduce the number of Supreme Court justices from 11 to nine, with new elections to fill the vacant positions. Especially controversial is a plan to create a judicial discipline tribunal that critics allege would put judges under political control.

Morena supporters argue electing all federal judges and magistrates would bring an aloof and elitist judicial system into closer contact with the Mexican people.

Piña argues the reform would put unqualified judges into power. “If the judicial reform is approved along these lines, the most qualified person won’t get the job,” she said in July.

Piña’s struggles illustrate the tactical challenge facing Mexico’s democratic transition-era institutions. Emphasizing technocratic excellence plays into AMLO’s argument that these institutions are out of touch with the Mexican people, while entering the political fray—and courting the opposition—undercuts their claim to impartiality.

In the meantime, the focus remains on Piña, who has been seen as one of the few constitutional brakes on López Obrador’s major initiatives. The opposition has focused fierce criticism on AMLO for seeking to limit the power of other institutions, such as the electoral authority, INE, claiming he targets them as obstacles to his rule.

A career judge, Piña began as a secretary for the Supreme Court itself in 1992 and worked her way up through the ranks, from judgeships to a magistrate position in 2000, winning appointment to the Supreme Court in 2015 under Peña Nieto, and earning a reputation for efficiency and competence.

“She comes from the bottom up,” said Rovira. “The general feeling was that she was going to a great job [as Supreme Court head] because she understood how the judiciary worked.”

Piña ended up in the job after AMLO did not get his preferred choice, Yasmín Esquivel, who was engulfed in a scandal over accusations of plagiarism (a court later cleared her of the charges). The Piña-AMLO relationship was frosty from the start—at a celebration of the Mexican constitution barely a month into her tenure as Supreme Court head, she remained seated as others stood to applaud the president. In a June interview with El País, Piña said she had never had a conversation with AMLO.

The court’s decisions under Piña piqued the president’s anger—especially a ruling in April 2023 that deemed unconstitutional AMLO’s bid to transfer the Guardia Nacional, a security body he’d created, to Army control. In June of that year, the court overruled AMLO’s “Plan B” attempt to place limits on the INE.

“López Obrador saw the chance to say, ‘Look, before the Court didn’t do anything for the people, now it’s ruling against everything, they’re against us,’” said Pablo Mijangos, author of a book on the history of Mexico’s Supreme Court. “He found in Norma Piña the perfect enemy.”

But Piña made errors too. Many pointed to her decision to meet opposition PRI party president Alejandro “Alito” Moreno last year.

“She lacked a real nose for politics, a certain political savvy in important moments, she was too aggressive, and now it’s very late to sit down and negotiate,” said Jacques Coste, a legal expert and columnist at Expansión Politica.

Critics fear the potential consequences of local and state authorities following the federal system in electing their judges, which they allege could open the way for organized crime to infiltrate the judiciary.

If AMLO can’t pass his version of the reform before he cedes power to Claudia Sheinbaum, she may be more willing to compromise, experts said. If the reform does end up being watered down, the impetus may come less from AMLO’s enemies, like Piña, and more from within his own party.

“I do see a very rich internal debate between different sectors of Morena,” said Coste. “That could end up changing a few points of the reform.”