By now, it’s almost a law of nature: In Latin America incumbents, and their parties, don’t win reelection. Incumbent parties have won just five of 31 presidential elections across the region since 2015, excluding the unfree and unfair votes held in Venezuela and Nicaragua.

Now, the anti-incumbency wave is coming for the left. Since 2019, leftist parties and presidents have won office practically everywhere, generating buzz about a regional pink tide. But centrist and right-wing candidates are polling ahead in the run up to Ecuador’s and Argentina’s October elections. Even in Mexico, where many thought Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s Morena party would cruise to victory in elections next year, an opposition candidate, Xóchitl Gálvez, is poised to give the incumbent party a run for its money.

“Give it a few years, and we’ll be back,” those on the left and center-left might think. Indeed, anti-incumbency means the region’s pendulum swings are getting shorter and shorter. But three long-term trends are also making Latin America increasingly hostile terrain for the left, and specifically the brand of social-democratic center-leftism that spread far and wide during the latest political cycle. If the sun does set on Latin American social democracy, it would mean the end of one of the political models that has done the most for the region historically—and could open the door to more reactionary and radical alternatives.

The Social-Democratic Turn

Since 2019, Latin America has turned left, but with a twist. The current crop of leftist presidents is decidedly more moderate than the last batch—more like former Uruguayan President José Pepe Mujica than Hugo Chávez. During the first pink tide, which swept the region from 1998 to 2015, the Chávez model was popular: More than a few presidents, buoyed by high commodity prices, tried to remake state institutions and their economies or go head-to-head with the United States. But from 2015 to 2018, voters fed up with slow growth and corruption (and fearing a repeat of Venezuela’s and Nicaragua’s authoritarian turns) sent the left packing.

Most leftist parties seem to have gotten the message. When they started winning national elections again, from Argentina to Bolivia and Brazil, it was by moderating. Twenty-first century socialism is out; 21st-century welfare states are in. But plans to advance social democratic reforms across the region haven’t exactly panned out, and even in places like Chile, where center-left governments succeeded before, they are now struggling.

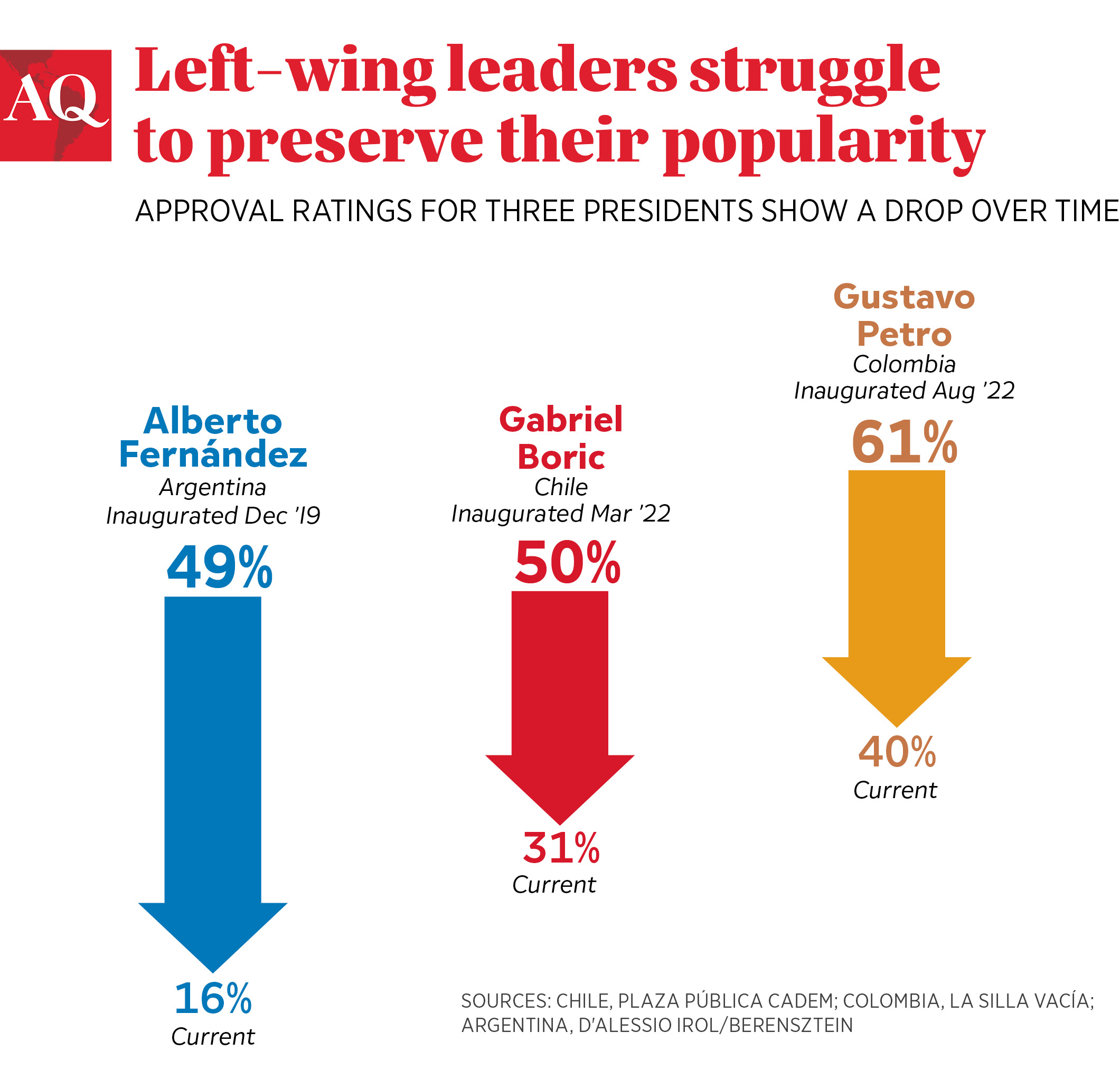

Gustavo Petro, Gabriel Boric, Alberto Fernández and Luis Arce have all struggled to enact promised reforms. Even Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who still has the wind at his back, has faced legislative setbacks. Part of the story is surely lower commodity prices, tighter fiscal belts, the pandemic and its repercussions, and in some cases, political inexperience. But that’s not all. The weakening of the region’s political parties, the accelerating pace of campaigns and rising crime all present particular challenges for the left.

The Party’s Over

When the left first swept into office across the region in the 2000s, the region’s political parties were formidable. Chávez, Rafael Correa, Evo Morales, Lula, Ricardo Lagos and Mujica differed from each other in most regards, but they all shared one quality: They had strong parties or social movements behind them, strengthening their hands as they negotiated with (or openly confronted) their opposition.

But during the 2010s, political organization started to break down. Parties across the region weakened. Social movements gave way to spontaneous, short-lived protests organized on social media. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Boric, Petro, Peru’s ex-President Pedro Castillo, and Guatemala’s President-Elect, Bernardo Arévalo, won office with new, loosely organized parties or coalitions and without the backing of formidable social movements. Except in Bolivia, no recently elected leftist president has taken office with a legislative majority.

That is an acute dilemma for center-left presidents. Their proposals—to reform tax codes, expand welfare states, or launch green transitions—require majorities they just don’t have. Several presidents have forged pacts with conservative opponents, but those come at a cost and don’t always last. Conservatives, who governed a broad swath of Latin America from 2015 to 2020, also grappled with divided government, but their plans for legislative change weren’t as grandiose.

TikTok Elections

Latin American elections in 2023 look completely different from decades past, with campaigns that happen as much on TikTok as in real life, frontrunners disappearing at the last minute and previously unheard-of candidates surging. This new modus operandi, coupled with voters’ frustration with the status quo, provides strong incentives to pledge sweeping overnight change. But there is nothing quick about building modern welfare states. Leftist presidents likely know this, but have little choice but to make impossible promises. When they struggle to deliver, as have Boric and Fernández, their poll numbers crash.

Latin America’s conservatives, who promise tough-on-crime policies and conservative policies on social issues, can accomplish important parts of their agendas through executive power. But there are no presidential solutions to the left’s big concerns, like unequal access to public services, wealth inequality or tax evasion—at least not moderate ones that respect checks and balances.

The Crime Trap

Yesterday, the issue dominating Latin American politics was corruption. Today, as Brian Winter wrote, it’s crime—and not just in historic hotspots, like Colombia or northern Central America, but also in once safer countries like Chile, Uruguay and Costa Rica, where cartels and gangs are making inroads.

The (hard) right has an answer in Bukele’s mano dura model, which has attracted a growing international fan club. Even Honduras’ Xiomara Castro, a leftist, has jumped on board. But as political scientist Lucas Perelló observed, the region’s leftist leaders seem to have no competing story to tell about how to tackle crime. Petro, who blasted Bukele’s mass prisons as “concentration camps,” promises “total peace” through negotiating with illegal armed groups, but this strategy has yet to bear fruit. Boric has boosted security and hardened its borders, but hasn’t stemmed a perception of weakness.

If there’s one exception to all these trends, it’s Mexico’s López Obrador, who built a mass party that holds a majority in the lower house of congress, passed reforms, and positioned a supporter, Claudia Sheinbaum, to succeed him. His secret? He’s a holdover from the first left turn, and he’s governing like it. Like Chávez, Correa, and Evo before him, he’s sought to loosen the constraints of checks and balances. He’s also empowered the military. But most of all he’s benefited from the dramatic weakening of Mexico’s traditional parties.

Is the sun setting on Latin America’s social democrats? Not everywhere. Uruguay’s Broad Front will probably win elections next year. Lula has much of his term left. But elsewhere, the bruising experience of the last few years could discourage future politicians from emulating Latin America’s moderate left. Social democrats like Uruguay’s Tabaré Vázquez, Brazil’s Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Chile’s Michelle Bachelet once deepened democracy and strengthened welfare states, providing an alternative to reactionary and populist models. If such alternatives run out, and the region’s center-left parties and candidates become a dying breed, it will be an ominous development.