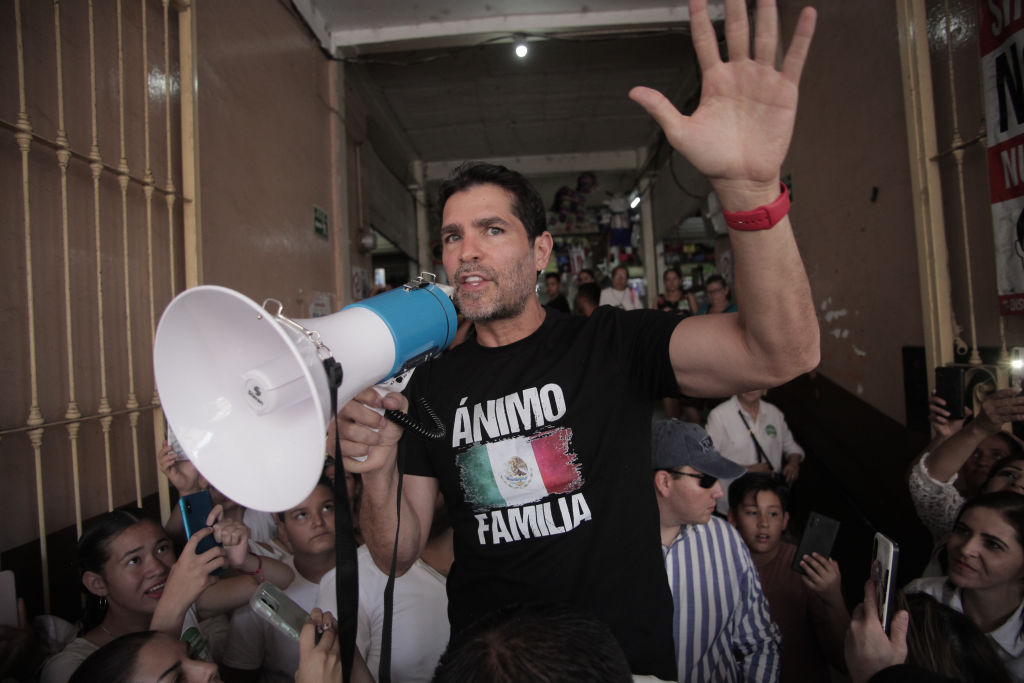

Eduardo Verástegui followed the playbook of right-wing, populist outsiders in his bid for Mexico’s presidency. The 49-year-old former pop singer and telenovela star turned Catholic activist built a social media following for his anti-abortion movement. A Trump ally, he brought a Conservative Political Action Conference event, or CPAC, to Mexico’s capital in 2022.

Verástegui traveled to Madrid to meet and smoke cigars with Vox’s Santiago Abascal, and attended Javier Milei’s inauguration in Argentina. “My fight is for life. My fight is for freedom,” he said, officially announcing his candidacy back in September. “It’s time to kick the same ones as usual out of power.”

But it turned out that he was too much of an outsider. On February 19, the country’s electoral agency, INE, announced an investigation into whether Verástegui illegally financed his campaign using foreign funds received from a Miami-based political consulting firm. He responded that the INE itself is corrupt—but, by January, his long shot independent bid for the presidency had already fizzled; he earned a small fraction of the signatures needed to appear on the June 2 ballot. It came as little surprise, given that Verástegui’s entertainment career, which more recently involved producing the far-right hit film Sound of Freedom, led him to spend years working in the United States and living in Miami—far from Mexico’s election circuit. And his postures, including a social media post in which he wielded a machine gun to threaten climate and LGBTQ+ activists, drew widespread derision and ridicule.

For many, his short-lived run felt like a dodged bullet—but it also raised a question. Why hasn’t a right-wing insurgent like Milei or Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro gained a foothold in Mexico, a country perceived as socially conservative and home to the world’s second-biggest Catholic population?

But without him in the running, all three of this year’s Mexican presidential candidates can claim a leftist bent. Academic activists raised frontrunner Claudia Sheinbaum of the governing Morena party. Xóchitl Gálvez, though a senator for the conservative PAN party, is a self-described “Trotskyite by origin.” Like his rivals, the Citizen Movement’s Jorge Álvarez Máynez is pro-choice and supports marriage equality. What explains the dominance of left-of-center politicians in Mexico?

Meet the candidates in Mexico’s 2024 presidential election

One obvious answer to the question concerns who these rivals are competing to replace: Andrés Manuel López Obrador, AMLO. Mexicans already voted against the status quo when they picked him in 2018, and his popularity has weathered storms since. Though he has long been framed as a leftist, he uses political language that can also appeal to conservative voters, whether by avoiding a stance on abortion or taking a combative approach to the country’s feminist movement. As such, AMLO’s broad-spectrum approach to voters has—at least thus far—left little room for a right-wing upstart to encroach on his Fourth Transformation.

Center citizens

This manner of politicking stretches back to where AMLO got his start: in the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) that dominated power for most of the twentieth century, partly by creating a space where figures with a range of politics could find a fit. “I think it’s true that Mexican politics has never emphasized left and right,” Noam Lupu, associate director of Vanderbilt University’s Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) told AQ, and he differentiated Mexico from countries in the Southern Cone or Brazil that suffered dictatorships. “Obviously, historically, the PRI was everything.”

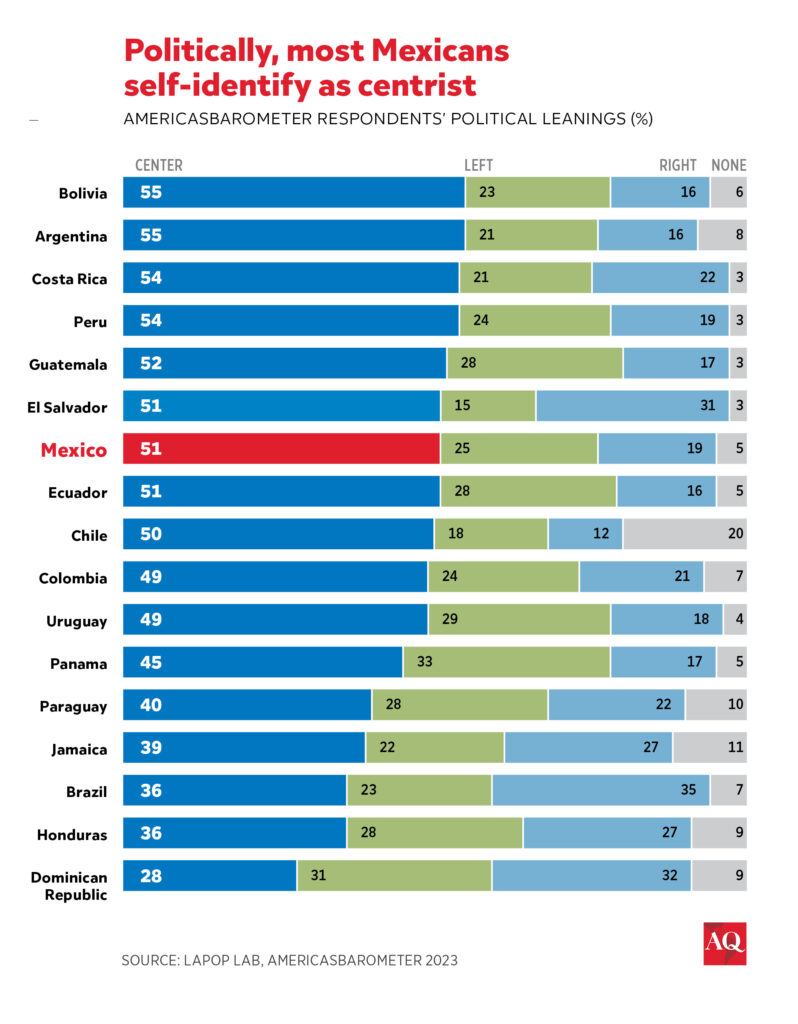

Nowadays, larger Latin American economies align with Mexico regarding how citizens self-identify their political leanings. Some 51% of Mexicans view themselves as politically positioned in the center, compared with just 25% to the left and 19% to the right, per LAPOP’s 2023 AmericasBarometer. Those figures place Mexicans on a similar spectrum to Argentina, Colombia, Peru and Uruguay. (Brazil serves as an outlier in that 35% of respondents—the largest portion out of 17 countries polled—self-identify as leaning right.) Likewise, Mexico lands on the progressive end of the Latin American spectrum when it comes to same-sex marriage.

Trailing Sheinbaum in the polls by double digits, Gálvez, whose Frente Amplio por México (FAM) coalition represents a range of parties and beliefs, has gone from publicly stating her support for abortion rights to telling a journalist, “I’m obligated to respect different visions.” Then, in February, she visited the Vatican to meet with Pope Francis in a move that would appeal to Catholic voters. (Sheinbaum followed suit two days later.)

Journalist Fernanda Caso told AQ that Gálvez, as a progressive, has moderated her approach in an electoral cycle where being for or against lopezobradorismo has taken the place of a left-right battle. That means prioritizing issues that define the divide. “We all know what she thinks, but she’s being careful not to lose the votes of a right that feels dissatisfied with López Obrador for his social policies or how he spends money or attacks institutions,” she said.

Yet Gálvez hasn’t been able to bring everyone into the fold. Last month, she invited Verástegui to join forces, saying, “Everyone who thinks that the country is on a bad path can work together.” Verástegui, who lumped Sheinbaum and Gálvez together as “communist twins” during his short-lived presidential bid, rebuffed her offer with a seven-point list of reasons enumerating his socially conservative views.

Such discord happens when faced with a president like AMLO, Diego Fonseca, a journalist and author of the book Amado Líder (Beloved Leader), told AQ. “That’s something that populism usually does to others,” he said, adding that AMLO’s movement has left the opposition parties with “an identity crisis, and they’re just in transition trying to understand what they’re going to be.”

AMLO, however, is slated to leave office in October. While a figure like Verástegui is what Fonseca describes as “marginal,” could someone else fill a potential vacuum down the line?

“In Mexico, you have a stew cooking on the [stove], but you still cannot see who is going to take advantage of that,” he said.