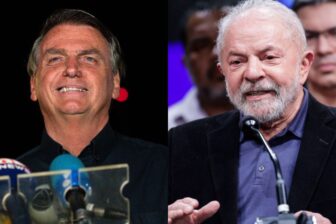

After a nail-biting vote count, Brazil’s electoral court declared Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva president-elect, just three hours after polls closed on October 30. Lula had 50.9% of the vote against President Jair Bolsonaro’s 49.1%, winning an unprecedented third term by the slimmest margin in the country’s history.

Fears of violence during the vote did not materialize, despite developments such as roadblocks set by the highway police across the country. As of this writing, Bolsonaro himself has been silent, but several close allies, including the powerful leader of the House of Deputies Arthur Lira, moved quickly to congratulate the president-elect.

AQ asked observers to share their reaction.

Zeina Latif, economic consultant

Brazil has a hard transition ahead—and the operative word is reconstruction. After a traumatic campaign, and the tightest margin on record, President-elect Lula will have to face the fears and demands of President Bolsonaro’s voters. These are challenges that were not mentioned in Lula’s victory speech. His next steps towards pacifying the country may not move financial markets but will give us a hint of his ability to renew himself, especially when it comes to negotiating—and working—with the new Congress.

Defining his economic agenda is especially important. There is a lack of trust on his party’s economic policies, considering the difficult scenario ahead for 2023. There will also be consequences of the recent fiscal excesses which will contribute to a deteriorating economy, a dynamic that most voters do not fully understand and for which they will tend to place the blame on his administration. This scenario means Lula urgently needs to define his economic team. Despite structural advances since Michel Temer’s administration (2016-2019) and incentives created for export sectors, the country’s economy has now been temporarily put on steroids by short-term stimuli that will leave behind a steep bill to be paid.

Lula has repeatedly said that his “will not be a Workers’ Party (PT) government,” indicating a more centrist administration. He repeated this pledge of a “government of Brazilians” during his victory speech, giving us reason to believe that he understands the scope of the challenge ahead, especially after the contribution centrist politicians made to his election victory. The president-elect seems to be seeking to revive the pragmatism he embodied during his first term. But pragmatism is not a synonym for reformism, much less of economic liberalism or macro-economic orthodoxy. Under the current scenario, pragmatism equates with a defined and consistent flight plan. The transition team has a herculean task ahead: pushing aside the PT playbook to include the contribution of the economic team that supported Lula this time around.

Let’s hope democratic maturity wins, on both sides.

Mauricio Santoro, Professor, UERJ – State University of Rio de Janeiro

Brazil is more ideologically divided than at any moment in its modern history. The president-elect will face a harsher scenario in his third administration than what he faced during his previous tenure as president. On the political front, he will have to negotiate with a much more conservative Congress, especially the Senate, and with a strong and well-organized right-wing opposition. It is also a more difficult international scenario than the global commodity boom of the 2000s: Namely, the pandemic and its effects, a war in Europe, slow-growth in China and the risk of recession facing many of Brazil’s economic partners.

Lula’s biggest challenge will be how to respond to urgent social demands—such as the large number of Brazilians facing hunger and unemployment—in a difficult fiscal situation and pressure from his hopeful voters who want quick change. Diplomacy will be the easier challenge for the president-elect. The prospects to reestablish dialogues around democracy, human rights and the environment—such as on climate change and curbing deforestation in the Amazon—with the United States and the European Union are excellent. The new government will likely also reinforce ties with the left-wing governments which currently rule most of Latin America. International support will also be important to ensure that the president-elect takes office on January 1, without the threat of something similar to the invasion of the Capitol in the U.S. if Bolsonaro refuses to accept his defeat, as he has repeatedly indicated he might.

Brian Winter, Editor-in-Chief, Americas Quarterly

In his victory speech, Lula said: “Starting tomorrow, I need to know how I’m going to govern this country.” And as the euphoria passes, that’s where Brazil’s focus will turn. It’s not going to be easy.

The election result confirmed: This Brazil is so much more conservative than the one Lula governed 20 years ago. Bolsonaro allies will govern Brazil’s three most populous states, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. Congress will tilt further right, ready to pounce—and yes, start impeachment proceedings—at the first sign of trouble. Given his past, they will hold Lula to a higher ethical standard than they did Bolsonaro. Lula is the most talented politician of his generation but I do not know how he will build alliances in a transactional Congress in this atmosphere of intense scrutiny.

Lula’s speech showed he understands the challenge: He started by thanking God, and ended by quoting Pope Francis and Jesus Christ. He said, “This isn’t my victory or the Workers’ Party’s.” Good words, but now we need to see the Cabinet appointments. The market believes we will see the return of a more moderate Lula. I think it’s possible but, for the moment, it requires a leap of faith.

What about Bolsonaro’s next move? All along, many pundits, myself included, said the closer the election result, the greater the chance he would attempt a “Brazilian January 6th.” I now wonder if we had it backwards. Brazilian conservatives performed so well in this election that many are now pleading with Bolsonaro not to destroy the movement by encouraging mass civil unrest—by burning the house down on his way out. The reaction by Brazil’s institutions, especially in Congress and the military, immediately closed down many paths. I suspect in the end Bolsonaro will allege fraud, never recognize Lula’s victory, but ultimately live to fight another day—preserving a political future for himself and/or his family.