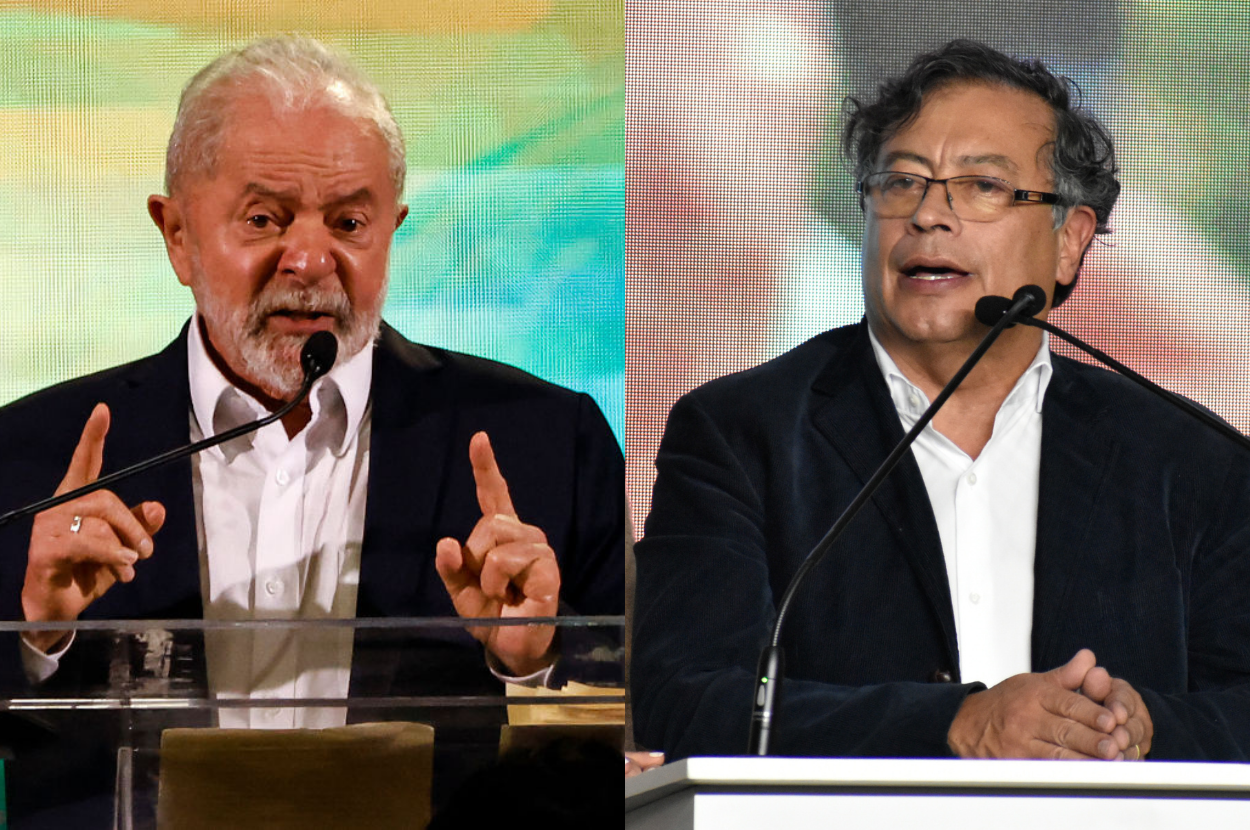

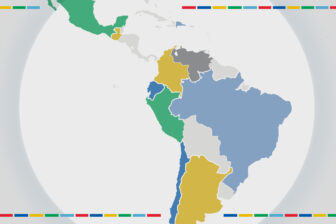

SÃO PAULO — The success of regional integration in Latin America, it is often said, depends on ideological alignment between governments. It’s no surprise, then, that the possibility of both a Gustavo Petro presidency in Colombia and a Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva win in Brazil has brought expectations for a new cycle of cooperation on the continent. Indeed, if Petro and Lula succeed, Latin America’s five most powerful presidents next year—in Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia and Chile—would all be, broadly speaking, ideologically aligned and, in principle, open to establishing constructive bilateral ties.

Recent years have seen a complete breakdown of regional presidential diplomacy, symbolized most prominently by the absence of dialogue between Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro and his Argentine counterpart Alberto Fernández. Yet while the return of open communication between Latin American heads of state—and perhaps even of regional presidential summits to which everyone, including Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, is invited—would be a contrast to recent years, those who expect a strong emphasis on regional cooperation in the event of a new “pink tide” may be disappointed.

Four main factors explain why ideological alignment may be a necessary but not sufficient condition for greater regional integration:

First, compared to the late 1990s and 2000s, which saw a series of meaningful regional initiatives, most leaders today face a far more challenging domestic scenario. Public frustration has built up after years of mediocre growth, rising inequality and a sluggish recovery after the devastation of COVID-19. There are few signs that the macroeconomic environment will improve anytime soon. Should he return to the presidency in October, Lula would likely have to dedicate far more time and energy to addressing Brazil’s internal crises than he did when he was president—and a fixture at major regional summits—from 2003 to 2010. Gabriel Boric in Chile, Fernández in Argentina and, if he wins, Petro in Colombia would all face a complex set of problems of their own. In the same way, ideological alignment is unlikely to change Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s essentially anti-globalist worldview, making meaningful engagement with the rest of Latin America more difficult.

Second, the return of great power politics to Latin America adds a layer of complexity to regional diplomacy that is unlikely to facilitate cooperation. Brazil’s armed forces, for example, have quietly expressed deep concern about Argentina’s strategic rapprochement with China, highlighted by the presence of China’s military-run space station in Patagonia. This issue is unlikely to be resolved merely by an amicable relationship between Fernández and Lula. As tensions between Washington and Beijing are set to increase and seep into other areas such as technology, finance and security, they also risk making a debate about the future role of Latin America more difficult, given that views on how to react to a “New Cold War” are bound to differ.

Third, while more uniform recognition of Maduro as Venezuela’s legitimate president may end the awkward and ultimately failed experiment of Juan Guaidó’s interim government, the main question remains of how the region should deal with an increasingly repressive regime overseeing an economic collapse so severe that six million citizens have decided to emigrate over recent years. The most likely scenario is that the country with the world’s largest proven oil reserves will remain a source of economic instability, continuing to act as a major obstacle to greater regional cooperation.

Fourth, and most importantly, expectations that regional cooperation may flourish in a new political environment tend to overlook the degree to which regional disintegration has been the major economic trend in Latin America over the past decade. This is a process that has little to do with the ideological orientation of national leaders. A renewed focus on commodity exports and a growing dependence on China help explain why intra-regional trade has grown much less than extra-regional trade in recent years. It also points to why manufacturing, traditionally the driver of regional trade, is losing relevance. A lack of economic complementarity and increasingly similar export patterns explain why intra-regional exports in 2021 amounted to only 13% of Latin America’s total exports, down from 21% in 2008. Bilateral trade between Brazil and Argentina actually declined in both relative and absolute terms over the past decade, and China overtook Brazil as Argentina’s most important trading partner. Similar trends are visible when looking at Chile’s and Uruguay’s trade ties, not to mention Venezuela’s trade ties with the region, which largely collapsed. Further north, Mexico and Central American nations have very limited trade ties to South America. Uruguay’s push to negotiate a free trade deal with China—the biggest buyer of its exports—is a clear sign that policymakers in Montevideo believe their future is tied to Asia rather than their neighbors.

That explains, for example, why Bolsonaro’s lack of regional leadership and attacks against Argentina’s government elicited far more limited criticism from Brazilian business leaders than his anti-China rhetoric, which ultimately led the Senate to push for the ouster of Foreign Minister Ernesto Araújo. Put differently, there are few organized interest groups powerful enough to convince presidents to prioritize the region.

This does not mean that it is not worth investing in regional integration—quite the contrary. A recent survey shows that seven out of 10 Latin Americans support regional integration—perhaps aware that it is crucial to addressing a myriad of common challenges ranging from transnational crime, migration and deforestation. In the same way, despite limited economic complementarities, part of the problem in the region is a lack of coordination in trade facilitation, the harmonization of rules of origin and, perhaps most importantly, the lack of a common vision to build a physical infrastructure to connect the region.

Petro and Lula, should they be elected, could well provide an opportunity for regional cooperation. But the odds will still be against meaningful progress in the near term.