This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on food security in Latin America

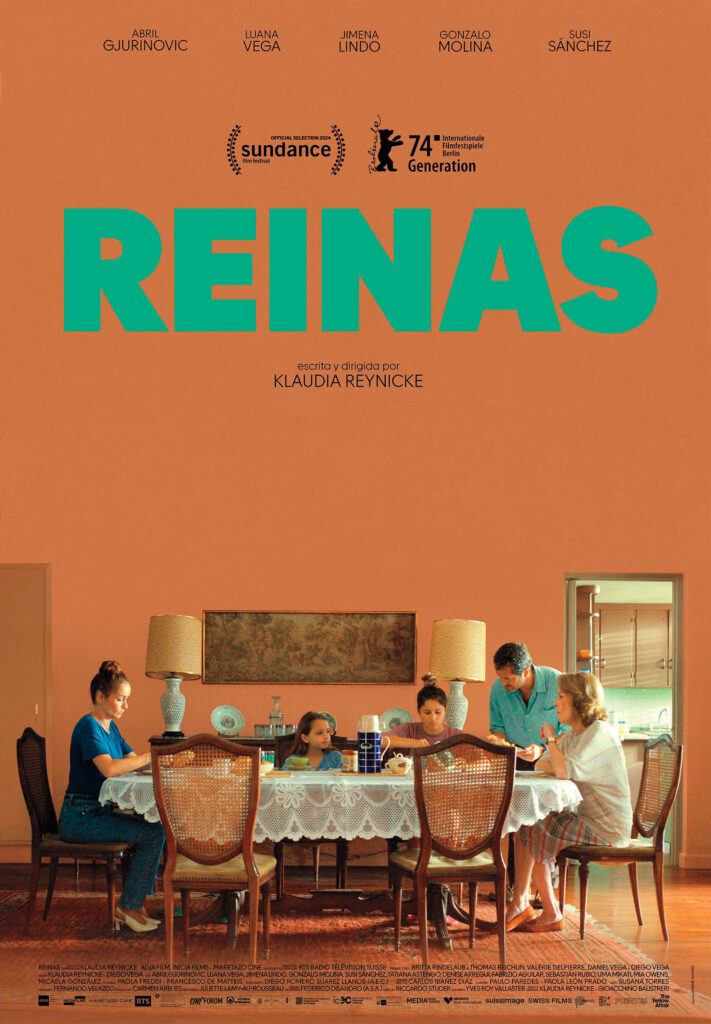

For most Peruvians old enough to remember, the early 1990s still conjure up vivid nightmares. Hyperinflation, food shortages, mass unemployment, car bombs—these were the years of intense economic turmoil, coupled with armed conflict between the government and guerrilla groups like the Shining Path. This unfolding chaos underpins Klaudia Reynicke’s Reinas, a family drama ultimately concerned with the emotional repercussions that unexpectedly stem from national crises.

In the summer of 1992, sisters Aurora and Lucía start preparing to leave Lima and move to Minnesota, where their mother Elena has found a job. Crucially, to fly abroad with a single parent, as minors they need signed and notarized permission from their distant father, Carlos. This task propels the film’s narrative, as Elena ushers her ex-husband back into their daughters’ lives in an effort to secure the required travel document.

Reinas

Screenplay by Klaudia Reynicke and Diego Vega

Distributed by Penny Black Media

Starring Luana Vega, Abril Gjurinovic, Jimena Lindo and Gonzalo Molina

Screenplay by Klaudia Reynicke and Diego Vega

Peru, Spain, Switzerland

2024

Directed by Klaudia Reynicke

Aurora and Lucía are initially reluctant to spend any time with Carlos. For starters, his life remains shrouded in mystery: They have no idea what he does for a living, where he resides, or how he spends his long spells away from the city. He initially seems like nothing but a stranger, yet little by little, a bond begins to form. Carlos makes possible much-needed release from the confines of the house, taking the girls to the beach and off-roading a truck across a sand dune, inspiring childish joy. For his part, a newfound stake in his daughters’ well-being awakens a previously dormant sense of paternal responsibility.

All the while, the clock ticks, bringing the girls’ day of separation from Peru closer and closer. In a recent interview, Reynicke spoke about how “the intensity of a moment”—which, in this case, “is the one of almost departure”—can bring to the surface all kinds of new and surprising feelings. The political and economic troubles that compel Elena to relocate also provoke changes in her family. After years of estrangement, Aurora and Lucía give their dad another chance. Carlos, in turn, realizes how much he wants to be more involved in taking care of his daughters.

Just as a state’s failures can excavate emotions that would otherwise lie buried, so too can they accentuate personal shortcomings. The repeated nods to Carlos’ recklessness and negligence as a father raise the question: Given the chaotic national circumstances, how much is he actually to blame? In the first scene of the film, he tells a client in a defensive tone, “I’m not really a taxi driver. I’m actually an actor. But I learn a lot from observing people.” The shame he feels about his precarious financial situation could be the reason he’s so elusive. In the Lima of the early 1990s, he would not have been alone, as middle-class workers often moonlighted as taxi drivers to make ends meet—a reality poignantly captured in Heddy Honigmann’s unforgettable 1993 film, Metal y melancolía.

Though much has changed over the last three decades, Peru is still home to many men in a similar position to Carlos. The country’s potential growth rate has seen a steep decline in recent years, and politically, both President Dina Boluarte’s administration and Congress have done little to assuage public frustrations over issues like poverty and organized crime. In 2022 alone, more than 400,000 Peruvians emigrated—the largest number since 1990.

Reinas reminds us of the more subtle, sometimes unimaginable ripples that political and economic catastrophes generate. They can reconfigure whole families and cripple working individuals’ sense of worth. By the end of the film, Aurora and Lucía do receive their dad’s permit. Family ties are mended, only to be broken apart again.