BOGOTÁ — Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro has proposed renegotiating the nation’s free trade agreement with the U.S., citing unbalanced corn imports from the North American country and Canada. The announcement wasn’t surprising: During his campaign, Petro said he wanted to amend the accord to protect Colombian agriculture.

But embarking on such an endeavor is a risky bet. On the political front, renegotiating free trade agreements presents significant challenges. By design, an accord to this kind is reached when both parties believe the benefits outweigh the concessions. Thus, any renegotiation to improve conditions in one area implies worsening conditions in another. It remains uncertain what Colombia would be willing to compromise during such a renegotiation, if anything. Signing a new trade agreement is time-consuming, spanning several years. After a potentially challenging renegotiation process, the new treaty would need approval from both the U.S. and Colombian legislatures. Given the upcoming 2024 U.S. presidential election and the absence of a robust political coalition for Petro, the prospects of achieving this before a change in government in Colombia appear doubtful.

From an economic standpoint, this strategy makes little sense. Colombia and all the other countries in the region need export-oriented policies. These policies should include reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade, expediting customs processing times for imports and exports, and eliminating bureaucratic red tape. Additionally, they should leverage standard World Trade Organization processes to address unfair trade practices. Agricultural subsidies from the U.S. and the European Union are particularly problematic since they artificially depress the production costs of several crops, which are then sold at world-market prices.

It’s essential to remember that Colombia’s national development plan law includes a provision for so-called “smart tariffs,” designed to safeguard national production against threats to food sovereignty (as opposed to food security). On a more positive note, in March, during a high-level dialogue with Colombia’s foreign minister Álvaro Leyva, U.S. State Secretary Antony Blinken offered to expand opportunities for farmers and small to medium entrepreneurs in rural areas “to get their products to global markets and reap the benefits of the U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement.”

A meaningful result from these discussions should be expected in the coming months, but history gives us a cautionary tale.

A lagging trade landscape

Sluggish economic growth, corruption scandals, and unmet social demands have led to a return of what is often referred to as a “pink tide”: a shift to left-wing governments that harbor skepticism towards market-oriented reforms, seek to distance themselves from the Washington Consensus, and intend to expand the government’s role in driving economic growth.

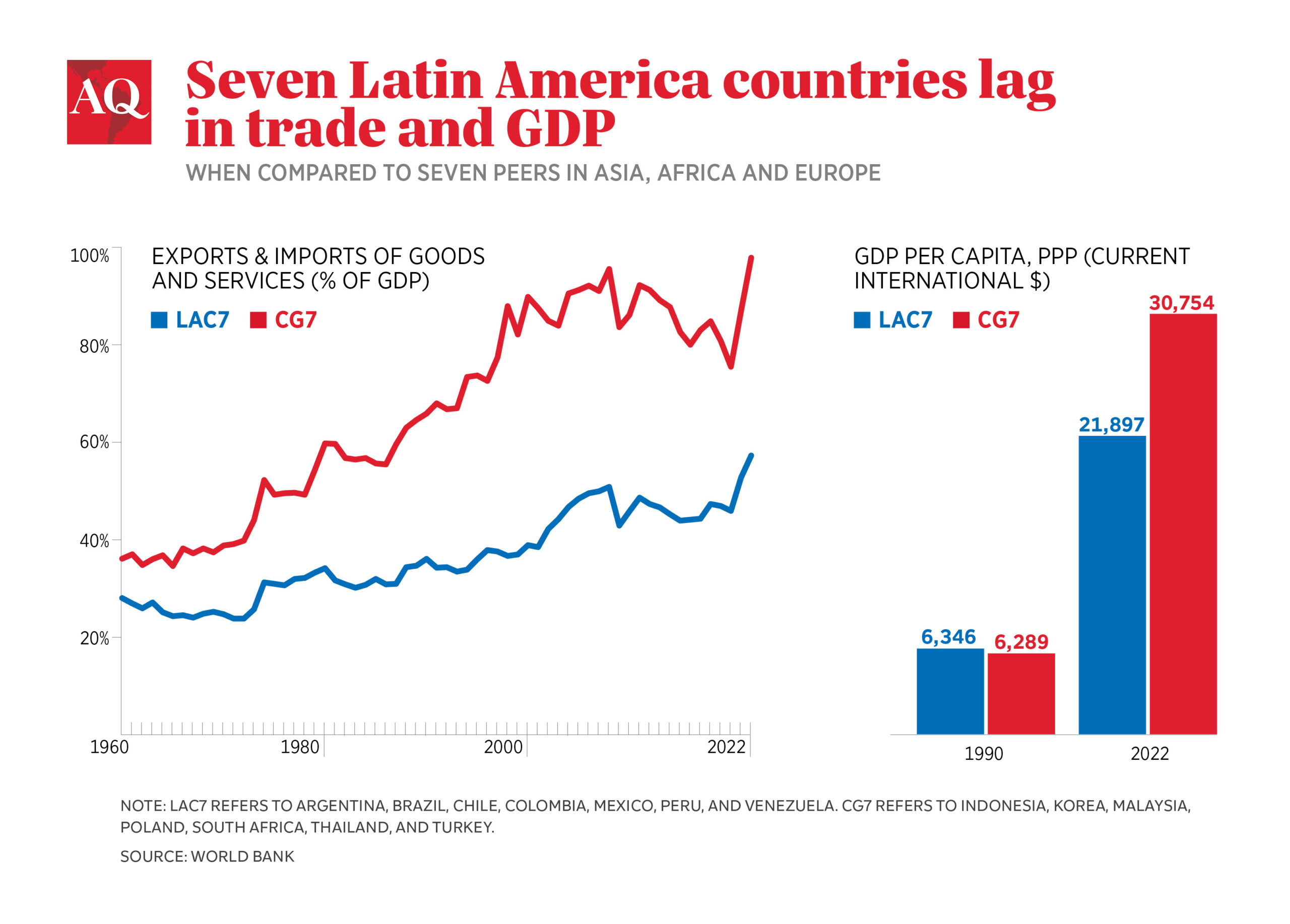

Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela (LAC7) are Latin America’s seven largest economies. They encompass almost 520 million people, nearly 80% of the region’s population, and about 85% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In 1990, their average per capita income stood at $6,346; by 2022, the figure rose to $21,897 (not including Venezuela due to the absence of reliable statistics). Despite internal and external shocks, the per capita GDP multiplied by a factor of 3.5 times in 32 years.

Comparing this result with seven countries with similar GDP per capita levels in 1990 ($6,289) tells us a lot. In the same period, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Poland, South Africa, Thailand and Turkey (CG7) saw their per-capita GDP surge by 4.9 times, a 40% difference in per capita income levels. This divergence in GDP per capita has profound implications for the well-being of the region’s inhabitants, particularly those that remain in poverty due to relatively lower economic growth.

For decades, understanding the patterns of economic development has been at the forefront of economic research. The factors that account for divergence in economic growth include the strength of institutions and the rule of law, the depth of financial and capital markets, the extent of democracy and liberty, and the quality of essential public goods, like security, infrastructure, health and education. Another critical element is openness to trade, measured as the sum of exports and imports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP.

Look at the diverging trade openness for these two groups. In the 1960s, CG7 countries had trade equivalent to 36% of GDP, just eight percentage points higher than the 28% for LAC7 countries. Fast forward through the decades for a startling conclusion: Although LAC7 doubled trade as a percentage of GDP, reaching 57% of GDP in 2022, the difference with CG7 countries, with trade levels of 98% of GDP, has significantly widened—to about 41 percentage points.

Higher trade levels go hand in hand with the diversification of productive and export activities and technological adoption. This leads to increased labor productivity growth, the basis for sustained growth, and rapid convergence to better per capita income levels. Although LAC7 countries are more open than six decades ago, their trade levels remain substantially lower than other success stories in recent decades.

Why not pursue a pragmatic approach?

Colombia would do well to emulate the example set by Brazil and Mexico. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) have adopted pragmatic trade strategies despite their left-leaning orientations. After a 20-year discussion in Brazil, Lula has pushed for the finalization of an FTA between Mercosur (comprising Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) and the European Union. He has (rightly) criticized the patronizing stance of the EU, home to several of the world’s largest cumulative CO2 emitters, for attempting to include penalty clauses if Mercosur fails to meet climate change goals. Hopefully, a reasonable deal will be reached in the coming months.

For its part, Mexico is now the U.S.’s leading trading partner, surpassing China and Canada. Since AMLO assumed power, Mexico’s trade levels have increased by about 12 percentage points to a record 89.5% of GDP. Its exports are substantial, diverse, and highly sophisticated; about 77% are manufactured goods, compared to just 16% in LAC7. The fact that this impressive performance in external trade has not translated into faster economic growth likely stems from other factors, such as security and institutional capacity, which are not keeping pace with trade expansion.

The misallocation of resources, labor and capital devoted to relatively unproductive activities is what numerically explains low productivity growth, a typical Latin American malaise. But behind this misallocation lay numerous factors, including an economy’s exposure to trade.

In a world where anti-globalization seems to be the norm, Colombia and other Latin American countries should not forget the lessons of recent economic success stories: Greater integration to international trade, coupled with rapid improvements in the coverage and quality of education, are critical for what the late Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert E. Lucas Jr. aptly referred to as “making a miracle.” Instead of revising and renegotiating FTAs, the region should concentrate on solving market and government failures that hinder economies from fully benefiting from the gains of trade in the first place.

—

Mejía is the Executive Director of Fedesarrollo, one of Latin America’s most recognized think tanks. He was Deputy Minister and Minister of Planning of Colombia from 2014-2018, leading the ministry in its implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals agenda. He has also held positions as Director for Macroeconomic Policy at Colombia’s Ministry of Finance, as well as researcher at Colombia’s Central Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington.