On the surface, the recent, highly publicized Twitter war between two Latin American presidents looked like a showcase of their opposite stances on security policy.

It began on March 1, after Colombian President Gustavo Petro criticized Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s security policies—specifically, the mass exhibition of gang inmates in what Petro called a “concentration camp.”

Petro urged the Salvadoran leader to learn from Colombia and Bogotá’s successes in reducing homicides, in part through social policy: “We didn’t build jails, we built universities,” Petro wrote.

Bukele retorted that “results matter more than rhetoric,” deriding Petro for claiming credit for long-term trends predating his presidency.

The presidents’ social media clash does highlight real contrasts in their security policies—most conspicuously, El Salvador’s widespread violation of due process under an ongoing state of exception that has seen nearly 2% of the adult population swept into jail.

But beyond the differences, Bukele and Petro’s security policies face similar challenges. They both focus on short-term results, and neglect reforms known to meaningfully address violent crime in the long term, such as judicial reform and combating impunity.

The Bukele strategy

In another social media exchange, Petro and Bukele traded allegations of negotiating with the criminal groups both are seeking to combat. “Better than making deals under the table … is to make them above the table,” Petro wrote, honing in on news of allegations by U.S. prosecutors that Bukele’s government had negotiated with gang groups.

Bukele retorted by noting that Petro’s son faces his own allegations of receiving bribes from drug traffickers in exchange for benefits under the government’s proposal for paz total, “total peace.”

Here, both leaders have a point. To start with, the issue with covert negotiations with gangs is that they can only go so far in maintaining peace. The tactic precedes Bukele’s presidency: As mayor of San Salvador, Bukele and the administration of Mauricio Funes are accused of negotiating similar agreements with gang leaders in exchange for reduced violence. Between 2011 and 2014, homicides dropped from 70 to 40 per 100,000. But it didn’t last: In 2015 homicides shot back up to 103 per 100,000 when relations broke down between the gangs and the government.

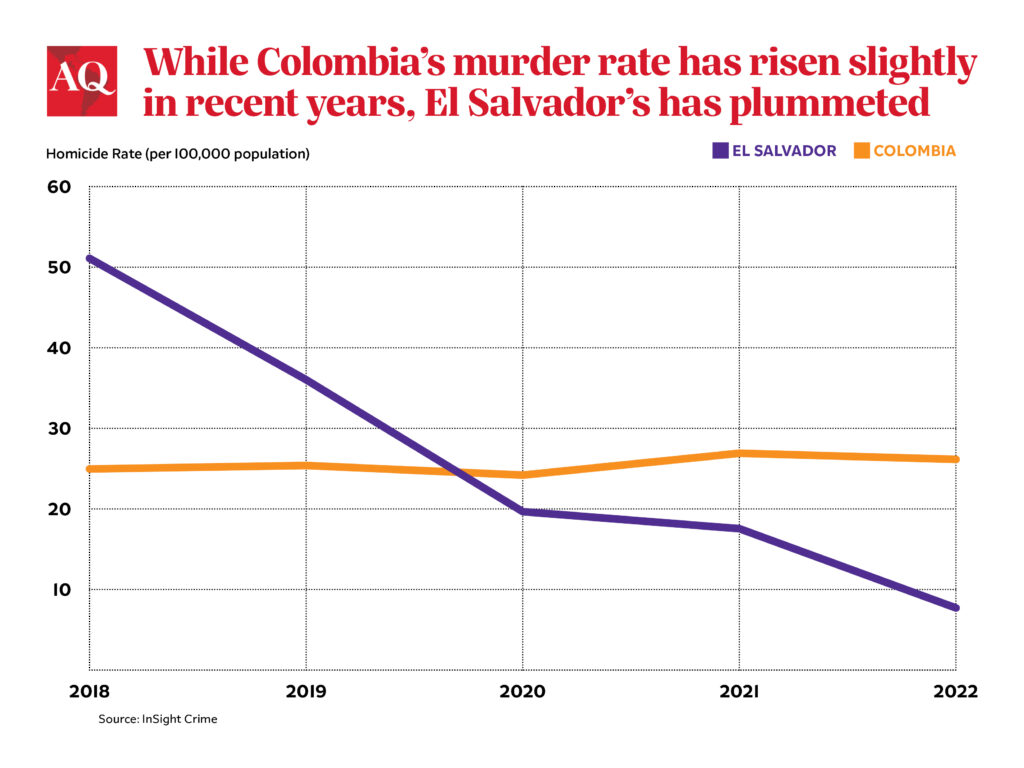

In fact, the current state of exception in El Salvador was a direct response to a spike of 87 murders in March 2022—which was allegedly the result of another breakdown in dialogues. With the state of exception nearing its first anniversary, the results are admittedly striking. In 2022, El Salvador registered a record low homicide rate of 7.8 per 100,000.

Understanding Bukele’s successes is key to understanding his challenges: what happens when due process is restored? Similarly, paz total is also fraught with caveats.

The Petro strategy

Paz total has the advantage of being more transparent: Petro campaigned on negotiating with armed groups, giving voters some buy-in to the process. His strategy also envisions the outright disarmament of armed groups—which is not the case in El Salvador.

The trick, of course, is ensuring that groups like the ELN and the AGC (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia) demobilize and do not exploit the disarmament of rivals to their advantage. The allegations that Petro’s son accepted money from drug traffickers, in exchange for including them in peace efforts, damage the Petro administration’s credibility in achieving this end. (Petro requested an investigation by the attorney general and said he hoped his son and brother, who is also facing complaints, would have the chance to prove their innocence.)

Still, paz total has its own preliminary accomplishments in reducing violence. Homicides in the city of Buenaventura fell dramatically as a result of a truce between the city’s largest gangs in preparation for talks with the government. Here again, the potential for rupture and subsequent violence is great. Can the administration deliver in the long run? This is likewise the question that should trouble Petro’s Salvadoran counterpart.

Impunity and authoritarianism

Both Colombia and El Salvador have some of the highest rates of impunity in world. In both countries, fewer than six of every 100 arrests led to convictions in 2019. Of course, under the current state of exception in El Salvador, those arrested effectively all go to jail. El Salvador could conceivably maintain low homicide rates under a permanent state of exception.

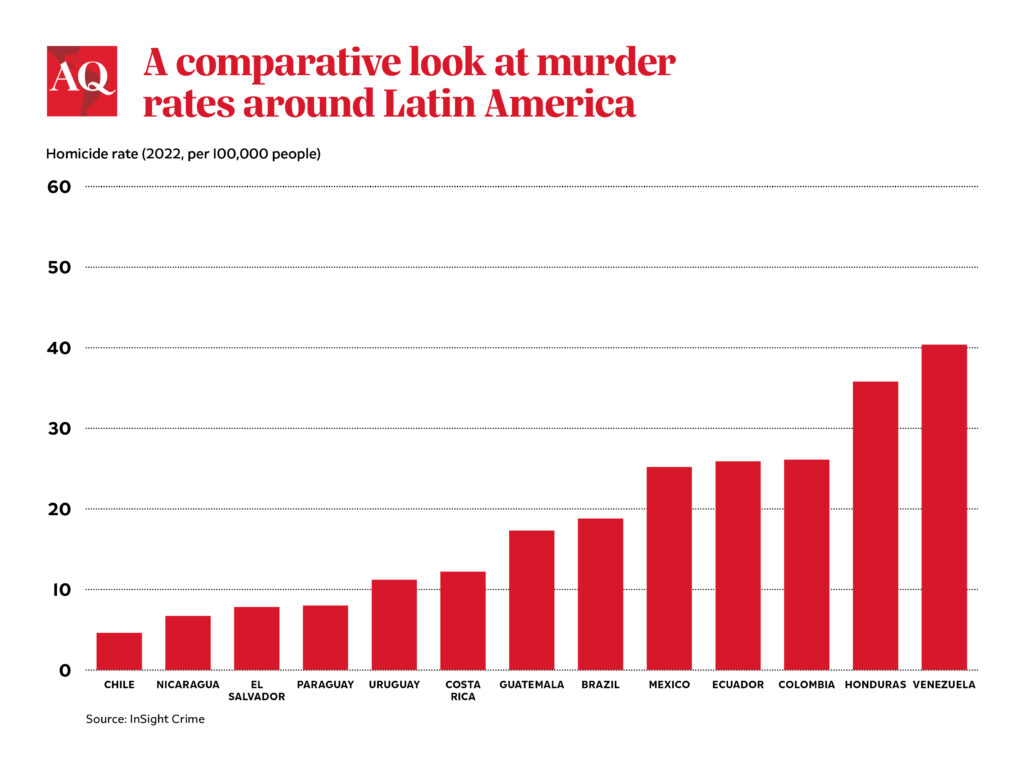

Bukele himself displays increasingly autocratic tendencies; dispatching troops to intimidate Congress and packing the Supreme Court to overrule presidential term-limits, all while maintaining high approval ratings. El Salvador under Bukele increasingly resembles nearby Nicaragua where incidentally, homicide rates are also exceptionally low.

Historically, dictatorships in Latin America have proven far more effective at combating violent crime than their democratic counterparts. But states with excessively high conviction rates afford few rights to the individual. If El Salvador is to remain a democracy, it will remain to be seen what happens with those imprisoned once—or if—the state of exception expires.

Petro is correct that civil society and social programs are key to combating violent crime. At the same time, it’s hard to see how violence will abate unless countries like Colombia and El Salvador address grievous deficiencies within their justice systems.

For his part, Petro has opposed building additional prisons. Given Colombia’s severely overcrowded carceral population, this stance seems misguided. In turn, the administration’s proposed justice reform does little to address impunity.

Colombia and El Salvador should look to peers where justice, while imperfect, is far more effective at punishing violent crime, such as Chile and Argentina. Even amid a recent crime wave, Chile, for example, maintains low rates of both homicides (4.6 per 100,000) and impunity (35% for homicides). Having enacted its own justice reform in 2001 streamlining criminal procedure and criminal investigations, Chile remains a model for the rule of law in Latin America.

Legally sanctioned or not, both repression and negotiation are inadequate security solutions in the long-term. Long-term success, in Colombia and El Salvador as elsewhere, necessarily entails the arduous task of reforming police forces and criminal courts and boosting social investment.

—

Rojas is an intelligence fellow at Florida International University’s Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy.