After witnessing the deluge of disinformation during the bitterly contested U.S. presidential election, Brazilians are preparing nervously for their own municipal elections on November 15, with runoffs roughly two weeks later. These elections are consequential: There are 5,570 municipalities in Brazil, and what happens this month could shape the political landscape for the presidential contest in 2022. Like the United States, Brazilians are voting amid a brutal pandemic, a deepening economic crisis – and a tidal wave of misleading and deceptive digital propaganda.

Since the controversial presidential campaign of 2018, several public institutions and social media platforms have taken steps to mitigate fake news, dangerous rumors, hate speech and defamation. But while new legislation and regulation could make a difference in the upcoming elections, recent examples of misinformation are proof that their risks to Brazil’s democracy are very real.

Brazil is a major social media power by any standard. Roughly 140 million of the country’s 212 million citizens are active social media users. It has among the largest cohorts of Facebook and Instagram users in the world. There is also a sizable following of Twitter and Youtube, and the country is experiencing a rapid surge of TikTok subscribers. In Brazil, as other countries, elections are shaped by the digital domain. Most political candidates have accounts and are active users of one or more of these platforms.

The 2018 presidential race reinforced deep political fissures in Brazil both online and off. Relentless social media campaigns on Facebook and bulk mailings on encrypted tools such as WhatsApp were immensely polarizing. Brazilians rapidly separated into several camps including hard core supporters of President Jair Bolsonaro and a fragmented opposition spanning the center and left. Like-minded groups stay isolated from one another online, reinforcing echo chambers.

Today, social media is very much a battleground in which politicians leverage their digital mobs for political advantage, and the vast majority of the offensive content in circulation is propagated by individuals with extreme right sympathies. In Rio de Janeiro, Mayor Marcelo Crivella, who is supported by the president, frequently uses social media to attack his rivals, including former Mayor Eduardo Paes. Crivella and Bolsonaro are adept at mobilizing their followers to the cause: Between October 9-21, 2020, for example, there were roughly 3,400 posts slandering Paes on Facebook, in public groups and verified profiles generating over 1 million interactions and 4.2 million views.

In São Paulo, mayoral candidate Celso Russomano’s campaign recently shared a video on WhatsApp falsely accusing leftwing candidate Guilherme Boulos of being connected to an irregularly occupied building that collapsed several years earlier. Russomano is also supported by Bolsonaro. According to fact-checking agency Aos Fatos, of the 44,052 Facebook posts related to the São Paulo municipal elections during the last week of October 2020, 4,675 were considered fake – and 2,492 were connected to candidate Guilherme Boulos.

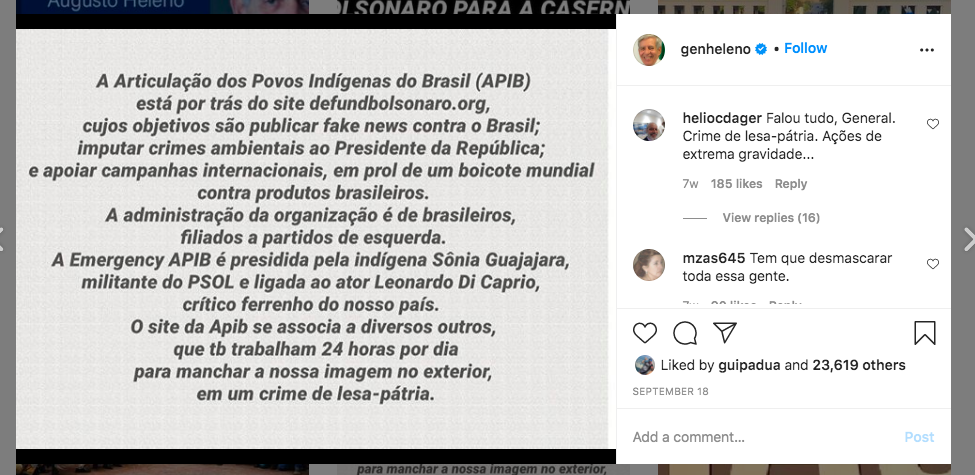

The extent of the misinformation is particularly concerning given the efforts already made to stem the spread. In fact, after reports emerged of widespread abuse on Facebook and WhatsApp during the 2018 presidential elections, the Brazilian state took action. Specifically, a Joint Parliamentary Inquiry Committee (CPMI) exposed a “hate cabinet” run by Carlos Bolsonaro, one of the president’s sons. This hate cabinet supposedly oversaw a sprawling network of blogs and social media profiles actively spreading disinformation and threatening opponents, including via YouTube, Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram.

Not surprisingly, targets of the hate cabinet included journalists, politicians, artists and conventional media considered to be critical of the president and his followers. A parallel investigation was also launched by the Federal Police to uncover who was responsible for organizing and financing demonstrations against the Brazilian Supreme Court. Again, Carlos Bolsonaro was singled out as the online coordinator. Investigations are ongoing and well-known financial backers are being identified. Still, the youngest Bolsonaro continues to spread lies on social media. His brother, Congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, has also used social media to spread doubt, without proof, about the fairness of the U.S. election.

This continues despite the Superior Electoral Court’s (TSE) launch in 2019 of a “fighting disinformation in the 2020 election” program to prevent such events from occurring in the runup to the vote. The program includes partnerships with roughly 50 public and private institutions, social media platforms and fact-checking groups. Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, TikTok, and Twitter have all signed agreements designed to increase direct report channels to the TSE, raise awareness about disinformation and misinformation among users, and improve the digital literacy of electoral justice staff. These same platforms are also increasing content moderation to limit online shenanigans.

While promising, these measures are just the beginning of a strategy to diminish digital malfeasance. This is because disinformation campaigns are not only professionalizing but also moving to new channels, especially encrypted ones. After WhatsApp introduced rules limiting the number of messages that can be bulk shared, Telegram – which has yet to sign any agreement with TSE – is now believed to be one of the primary vectors for extreme right-wing content in Brazil. In some cases, fake news and extremist content is also being trial-ballooned in video platforms such as Youtube.

To be effective, strategies to disrupt misinformation and extreme content need to be comprehensive. This begins with identifying the actors and tactics used by these groups as was recently demonstrated by the Election Integrity Partnership in the United States.

To date, most efforts to take down offensive content are focused on specific platforms: As the Brazilian case shows, there is always a risk that some technology companies will refuse to play ball. In such cases, governments will need to introduce rules to incentivize cooperation and punish defection. Social media companies too will need to carefully upgrade their content removal policies. Failure to do so is not just dangerous for elections, it is fatal for democracy.

—

Muggah (@robmuggah) is a co-founder of the Igarapé Institute and principal of the SecDev Group. He earned his PhD at the University of Oxford. He is author of Terra Incognita: 100 Maps to Survive the Next 100 Years with Penguin/Random House. Francisco (@papfrancisco) is a researcher at the Igarapé Institute and a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Hurel (@LouMarieHSD) is a researcher at the Igarapé Institute and a PhD Candidate in at the London School of Economics (LSE).