Elvia León, the youngest of seven children, wanted to leave Bomintzhá back in 1987. “I told my mother that I didn’t want to live in that kind of poverty, and she supported me.” Her father was less pleased with her plans to abandon their small community in Mexico’s Hidalgo state to study in the city of Querétaro. “The culture here is that women are meant to be at home, doing domestic chores.”

But more than two decades later, her father, suffering from prostate cancer, followed her to Querétaro. At the end of a long administrative career in the Mexican public health system, León found herself juggling the care of each parent until her mother passed away at the age of 92 in 2023. Along the way, León struggled with a variety of obstacles, from substandard elder care centers to a public transit system unable to handle her mother’s wheelchair.

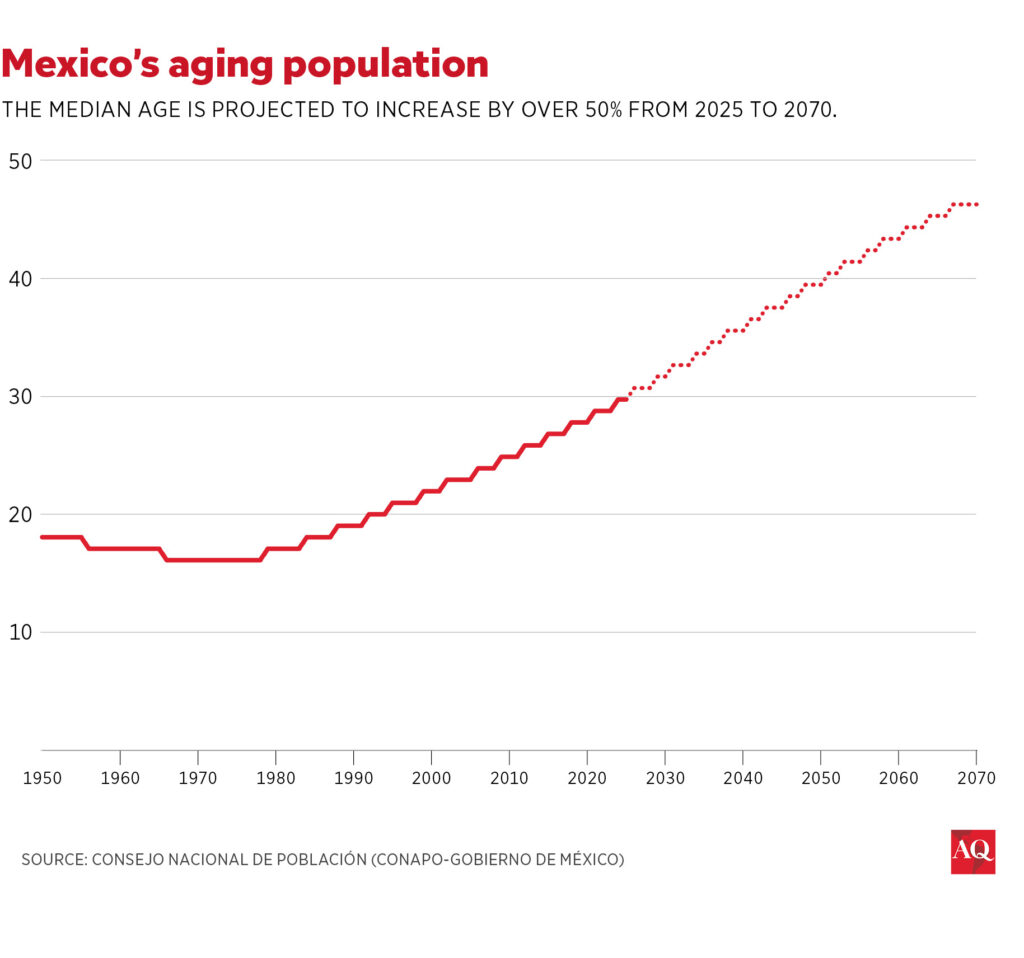

Mexico will soon have to reckon with these kinds of challenges on a mass scale for one big reason: The country is growing old. Long able to trumpet having a large, young working population as a comparative advantage over its North American peers, Mexico’s median age will jump from 18 in 1987, when León left home, to 40 in 2050, per National Population Council projections. The country’s 60-year-long demographic dividend, the period when the working-age population outnumbers dependents, will come to an end in 2030—just as Claudia Sheinbaum’s presidency draws to a close.

Is the country ready for the big shift ahead? Already, the potential demand for elderly care services is 15 times higher than for childcare services, according to Inmujeres. Many argue that one solution lies in building a national care system through a network of services for children, people with disabilities, and the elderly while relieving women of the burden of unpaid domestic labor. I met León at a November conference focused on developing such systems. The Mexican government has started laying the groundwork, but time is short.

A silvering region

The demographic shift is happening fast, and Mexico is not alone. Across Latin America and the Caribbean, plummeting birth rates have intersected with soaring life expectancy and, by 2100, more than 31% of its population is expected to be over 65—higher than any other region. It took 56 years for Europe’s share of the population over 65 to grow from 10% to 20%, a mark it hit around 2019. Latin America and the Caribbean won’t reach the same level until 2055, but will do so in half the time.

The region will also reach the mark with less than half the per-capita GDP of high-income countries. “There’s a saying: ‘Latin America gets older before it gets richer,’” says Pablo Ibarrarán, head of the IDB’s Social Protection and Health Division.

This future scenario has an impact on women in more ways than one. For starters, women in Latin America not only live longer than men but are more likely to live in poverty and depend on care as they age. Women are more likely than men to be caretakers and to give up work to do so.

Both are issues in Mexico, where 25% of the 65-plus population reports being dependent on care for daily tasks—the highest rate in Latin America—and women in this age group tend to be more care-dependent. At 47%, Mexican women’s labor-force participation already lags the rest of the region, and 56% of those who do work are informally employed, limiting their access to social protections such as pensions. IDB research found that women between the ages of 50 and 64 who took care of an aging parent are less likely to work, and work fewer hours. There was no change among men.

But an aging population offers a potential opportunity as well, including job creation, and the country will need more women in the workforce. The number of Mexicans over 65 who need care will triple to 7.3 million by 2050. “We need trained people,” Verónica Montes de Oca, a gerontologist and expert in aging populations at UNAM’s Institute of Social Research, told me. She added that Mexico needs a shift from thinking of the elderly as medical patients to a more holistic approach.

The long game

The care burden borne by women has sparked a movement in Mexico and other parts of Latin America to recognize, reduce, and redistribute the work through comprehensive national care systems. In 2015, Uruguay became a regional pioneer when it established its National Integrated Care System, and countries from Chile to Costa Rica to Ecuador have followed.

None of these systems have been built overnight, and Mexico’s won’t be either. In November 2020, the lower house of Congress approved a reform to create a national care system, but the measure has remained frozen in the Senate ever since.

Supporters gained new hope in October when Sheinbaum included a pledge to build a national care system among the 100 promises she made during her inauguration. But, at the conference I attended, the incoming head of the newly created Secretariat of Women warned that it probably would not be achieved by the end of Sheinbaum’s term.

The price tag is a hurdle. In 2023, the finance secretariat estimated a national care system would cost somewhere around 1.4% of GDP, a tall order when the 2025 budget relies heavily on public spending cuts. In December, Sheinbaum’s government launched a pilot project involving 12 early education centers to support women working in maquiladoras in Ciudad Juarez. The president also rolled out a pension program for women aged 60 to 64 of 3,000 pesos, about $150, every two months.

These payments can only go so far, says Ibarrarán. “The pensions for the elderly that the government gives, they’re good and they’re a huge investment,” he told me. “But they’re not going to lift people out of poverty.”

A system takes root

Still, the seeds of a system are being planted. In December, the IDB announced it will support Mexico’s efforts to establish a national care system in partnership with the new women’s secretariat and other government agencies. Ibarrarán, who is part of the partnership team, pointed out that the government has launched a program involving a health census to help develop home care for the elderly and disabled.

While Mexicans wait for the seeds to bear fruit, state and municipal governments pick up the slack. In 2017, Mexico City, which has the largest per capita elderly population in the country, established the right to care and the creation of a care system in its constitution. States such as Nuevo León and Estado de Mexico have taken steps to develop systems, and in February 2024, Jalisco became Mexico’s first state to approve a “care law” to create an integrated care system.

Elvia León plans to visit Jalisco to learn about local care efforts for the elderly. She is developing a proposal for day centers drawing on public funding where the elderly can socialize and get nutrition, physical therapy, and other services. “The very first thing I want to do is open one of these centers in the town where I’m from,” says León. “And give [the elderly] the attention and the love they need.”